For almost two decades, the press-averse Paul Allen has been a favorite target of Seattle media in general and Seattle Weekly in particular. We’ve slammed him for his stadium-financing shenanigans, questioned his real-estate maneuverings in South Lake Union, and mocked his profligate spending and vanity investments. As the reputation of fellow Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates has fallen—during the OS and browser monopoly wars of the ’90s—and risen with his new foundation, Allen’s has become a punch line. He’s the guy who settled for too little company ownership (Gates badgered him down to a 36 percent stake, later diluted to 30), retired too early (1983—yes, really, two years after the IBM PC debuted), and has squandered too much on yachts, mansions, dot-com failures, Hollywood partnerships, pro sports teams, and cable companies. Then there’s his 1998 sexual-harassment suit and reclusiveness (which led 60 Minutes‘ Lesley Stahl, in their recent interview, to compare him to Howard Hughes). We’ve said some very mean things about the guy, who recently recovered from his second life-threatening bout with lymphoma.

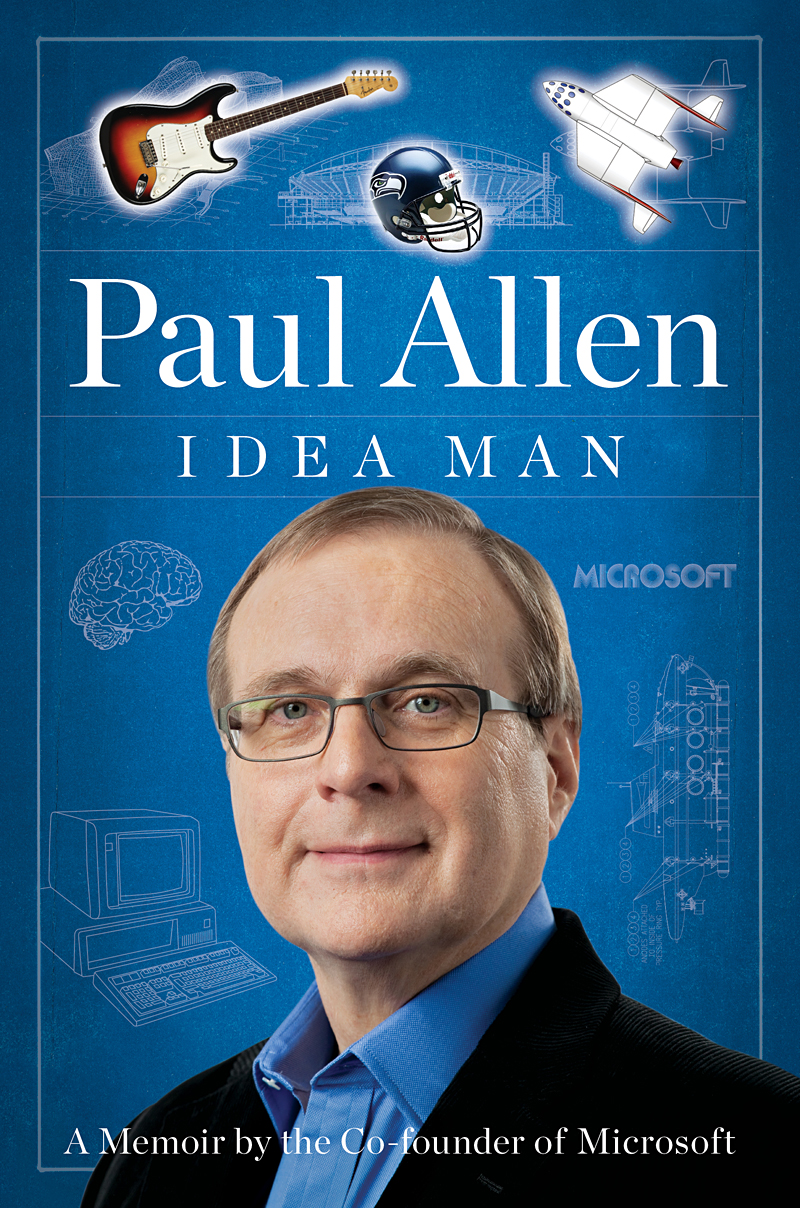

Well, Paul, having read your new auto-biography, Idea Man (Portfolio Penguin, $27.95), we’d like to say we’re sorry—we take at least some of it back. Aided by a team of editors (likely led by former Seattle Times reporter David Postman, now on the Vulcan payroll), Allen’s account of Microsoft’s origins is wonderfully enthusiastic, with some piquant details. To keep alert during marathon coding sessions, Gates would lick dry, powdered Tang off his orange-stained palm. On an early business trip, Allen realized Albuquerque was in New Mexico, not Arizona. And in a felicitous iambic phrase, he cherishes “the classic mainframes of my youth.” The second half, detailing his post-Microsoft life, is an opaque, sexless, blame-others recital of The Problems of the Rich. It’s dull, dull, dull; you can sense his editors’ frustration at packaging each milestone—Trail Blazers, Seahawks, EMP, Starwave, philanthropy, Charter Communications—into a manageable, relatable chapter. Because when you’ve met one billionaire, you’ve met them all. The yachts and the safaris and the celebrity name-dropping are all the same. Idea Man is half a good idea.

Microsoft went public in 1986; the following year, Howard Schultz and an investment group bought Starbucks (now celebrating its 40th anniversary), which had its IPO in ’92. Today the companies are worth about $220 billion and $27 billion, respectively, and both are precious worldwide brands for Seattle—advertisements, if you will, for our brains, good taste, and entrepreneurial zeal.

Because it dishes less dirt and is chiefly a triumphalist turnaround account of Schultz’s reclaiming the CEO’s chair in 2008, Onward (Rodale, $25.99) has gotten less attention than Allen’s memoir. But they actually make for good parallel reading—a pairing of introversion and extroversion, of programmer and salesman. (And guess who, of course, is mentioned in both their indexes: Bono.) They’re a perfect generational match: both born in 1953, both NBA team owners. If shy Allen is the wounded, touchy guy who resents/adores his old partner, Schultz is the cocky soloist who’s never had an equal partner at Starbucks. After its stock fell 47 percent in ’07, he fired his successor and rode back on a white horse to claim the victory garlands. (Besides cost-cutting and U.S. store closures, expansion in China and other foreign markets surely saved his ass.)

By contrast, Allen is the poor nebbish, still feeling hurt and aggrieved after all these years, with his face pressed against Microsoft’s storefront window. Reading the book, you keep hearing his plaintive voice . . . Bill! Bill! Let me in! Everything is forgiven! Read Chapter 13, fire Ballmer, and we can reclaim the old magic! The Internet was my idea! We can beat Google and Apple and save the company!

Of course, it’s not going to work that way. Once you’re out, you’re out. Schultz never really surrendered power at Starbucks, and Allen never should have quit Microsoft, no matter how disrespected he felt there. The two books provide a harsh, useful lesson for today’s aging, white, male Baby Boomer executives: Don’t quit when you’re ahead. Early retirement equals death—or in Allen’s case a kind of pharaonic entombment in his unexpected fortune. While the ever-vigorous, forward-moving Schultz kept adding management hats (while still taking time for three-hour bike rides on Kona), the sickly Allen underwent a kind of regression. He recreated everything he loved from his youth—sci-fi, sports, gadgets, Hendrix, movies, etc.—and walled off the rest of the world.

Onward‘s mix of inspirational slogans, self-serving anecdotes, and management minutiae doesn’t make for great reading. But Schultz pisses on absolutely no one, and never the people he’s fired. He’s a consummate glad-hander, but also at his core a tough kid from Brooklyn, a striver whose parents were working-class, unlike Allen’s solidly educated Wedgwood clan. His book will be bought and studied by every manager at Starbucks, all looking for tips on how to please their boss. Yet there are some nice little details, like the discovery—in 2008!—that Starbucks’ cash registers were still running on an MS-DOS platform. And when Schultz writes that “emotional connection is our true value proposition” in coffee, it’s a reminder of what Microsoft never had and never will. People love their iPhones, and they hate crash-prone PCs.

Allen’s book will be purchased mostly by graying geeks who fondly remember BASIC and 8-bit Altair computers. Idea Man leaves you feeling a little sad, actually, almost sorry for a lonely guy whose paper wealth has plummeted from around $40 billion to $13.5 billion. If, with his honestly acquired loot, he’s chosen to live his life like a James Bond supervillain, let him. But he’d probably be happier and more socially adjusted today if he were a librarian or teacher, like his parents.

Onward, meanwhile, is too proud of itself by half, yet for all Schultz’s bad ideas— Via! Smelly breakfast sandwiches! Retail clutter!—he’s maintained focus on friendly, clean coffee shops where people feel invited to gather. And where, logging onto the Wi-Fi, customers owe a distant debt of gratitude to Allen’s only child, MS-DOS.

Should he ever lose the rest of his fortune, it might actually be a blessing for Allen—a chance to leave the gated compound, get a job, and mingle with the public. And Starbucks is always hiring.