What’s the most deeply affecting operatic subject matter? Love? Death? Not for me—it’s forgiveness, which is why I’m a lake at the end of Falstaff, Candide, and The Marriage of Figaro, but not necessarily after La Bohème or Madame Butterfly. Idealism runs a close second, and these are the twin themes of the neglected but charming and moving Don Quichotte by Jules Massenet. Unlike Puccini, his only rival in popularity during his career, Massenet’s method was sentiment and poetry rather than dramatic thrust; opera’s master pâtissier, he skillfully pushed—caressed, really—emotional buttons with a velvet glove.

If that sounds like an odd fit for Cervantes’ sprawling picaresque, Massenet distilled the novel to the story of the knight errant’s unrequited love for the lady Dulcinée, and drew from it a subtly bittersweet study of disillusionment. By the time he wrote the piece, in 1910, two years before his death, he knew how to make even a soft, sustained background string chord tell emotionally. His serenade for the Don in Act 1 recurs as a musical reminder of Dulcinée; its slowly descending outline is echoed in many of the opera’s melodies, making them sound like so many feathers drifting gently to the ground.

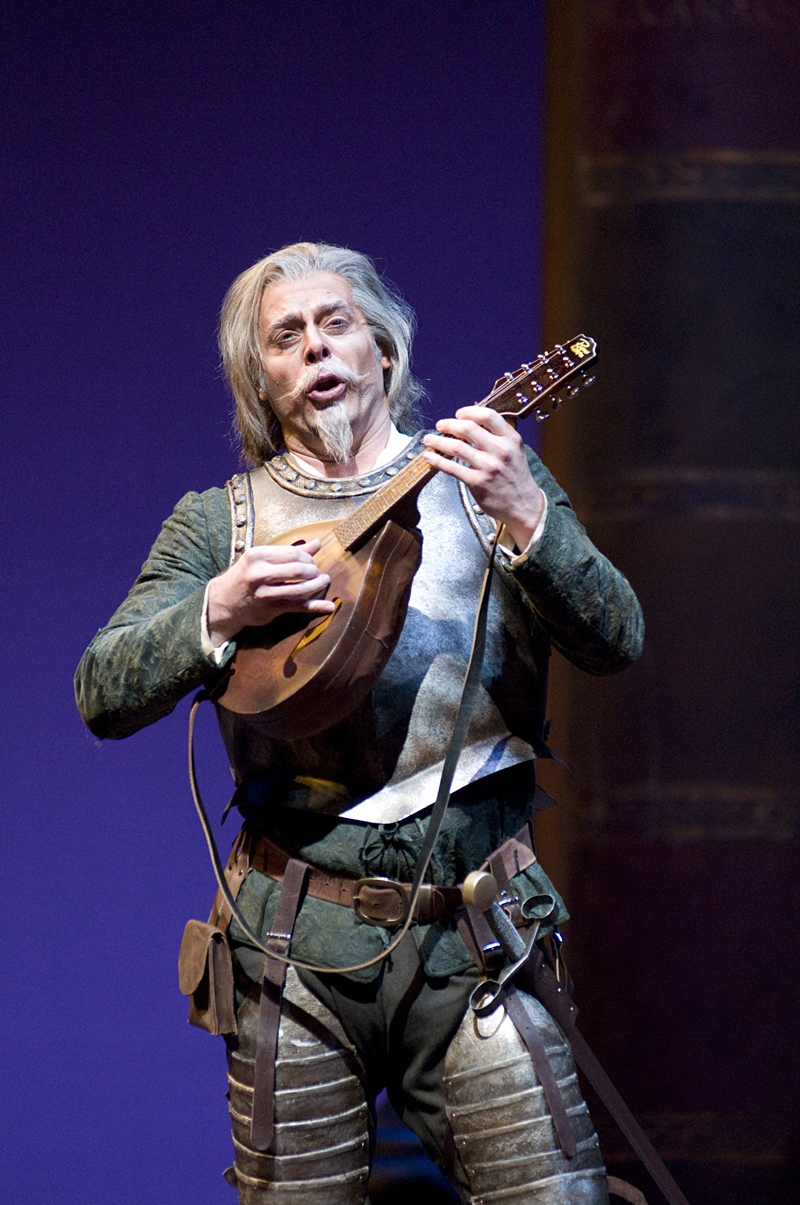

Seattle Opera’s production emphasizes the opera’s literary ancestry. Donald Eastman’s fanciful set is full of enormous books, quill pens, and inkwells—handsomely done, but unwieldy to move around and act around. Pertinent quotes from Cervantes (in translation) are projected on the scrim before each scene. In the title role (in the Wednesday/ Saturday cast), John Relyea beautifully suggests the poignancy of a man whose aged body is unable to match the youthful vigor of his bravery and chivalry. As Dulcinée, who we’re told is 20, Malgorzata Walewska’s dark-rum voice takes some getting used to. (Apparently Massenet himself was in love with the much younger singer who created the role, which is why he wrote this soubrette part for a mezzo-soprano.) Quichotte’s squire Sancho Panza is tasked with making a challenging transition from comic relief to the pathos of his master’s death scene; Eduardo Chama does so effectively.

Also admirable—quixotic, you might say—is Seattle Opera’s ongoing commitment to repertorial novelty in economically difficult times. Or at least its commitment to Relyea; he’ll be back next season for Verdi’s rarely staged Attila.