You’ll be scrambling the rest of the season to find a more riveting exploration of fraternal bonds than Tarell McCraney’s The Brothers Size. Newcomer McCraney’s text swaggers with ambition; better news still is that this production achieves many of the lofty goals he sets.

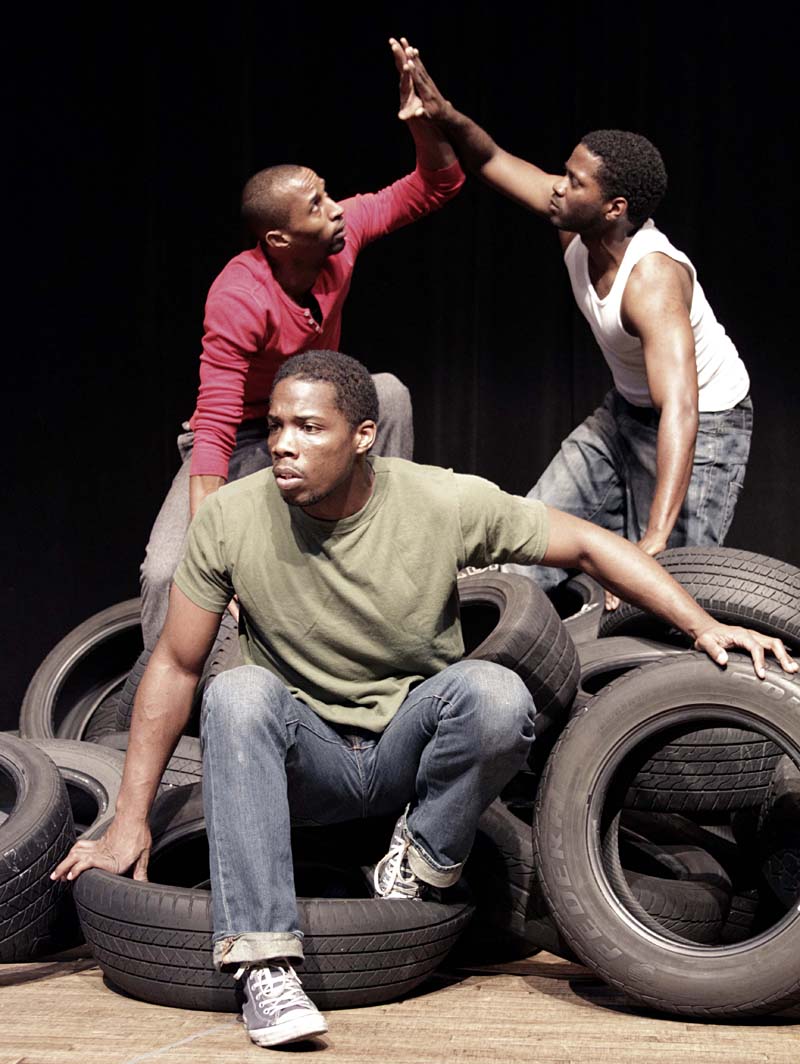

It’s a conventional enough plot: Older brother Ogun (Yaegel T. Welch) has a garage in Louisiana to call his own, but he’s also saddled with bringing up his ne’er-do-well kid brother, Oshoosi (Warner Miller), who’s fallen under the spell of a homie he met in prison, Elegba (Eddie R. Brown III). Essentially, Oshoosi must claim kinship in one direction or the other—decide who’s his real brother.

McCraney weaves his tale with a small arsenal of wildly theatrical devices. For one, the three characters often announce their arrivals, departures, and reactions. Similarly, he infuses what first seems a contemporary fable of the African-American underclass with older African cultural touchstones. The Brothers Size offers a surprising mix of music, balletic movement, and poetic prose that brings to mind both Chappelle’s Show and the hard-nosed Chicago jive of David Mamet’s best work.

Sure, there are florid speeches that make their point long before the actors have delivered all their lines, but McCraney has such a well-developed palette for language that his only crime is serving up too many richly crafted phrases. (And for all its lyricism, the script moves seamlessly from African ritual to Southern slang.) Some will find the f-bombs and frottage objectionable, but having spent several years in New Orleans pre-Katrina, trust me: I know dozens of locals who talk, act, and think just like these three.

If anything does ring false here, it’s McCraney’s second-act revelation that Oshoosi’s prison buddy isn’t hanging out for altruistic reasons—he’s after something, but what could it be? The reversal is a tired stage trick that feels forced and phony in such a fresh work. (The play premiered in New York in 2007, when McCraney was 27.) Otherwise, the principals are spectacularly memorable, Geoff Korf’s lights and creative visual accents provide an eerily impressionistic counterpoint to the text, and director Juliette Carrillo sets a ferocious rhythm that has each scene pouncing out of the blackout and into your lap.

So while we get the familiar “devil on one shoulder, angel on the other” contrivance as Oshoosi teeters between redemption and perdition through most of the play, much of what’s written here is brilliant. McCraney provides not only glimpses into the souls of his characters; he reveals much about who we consider to be our own brothers, and why.