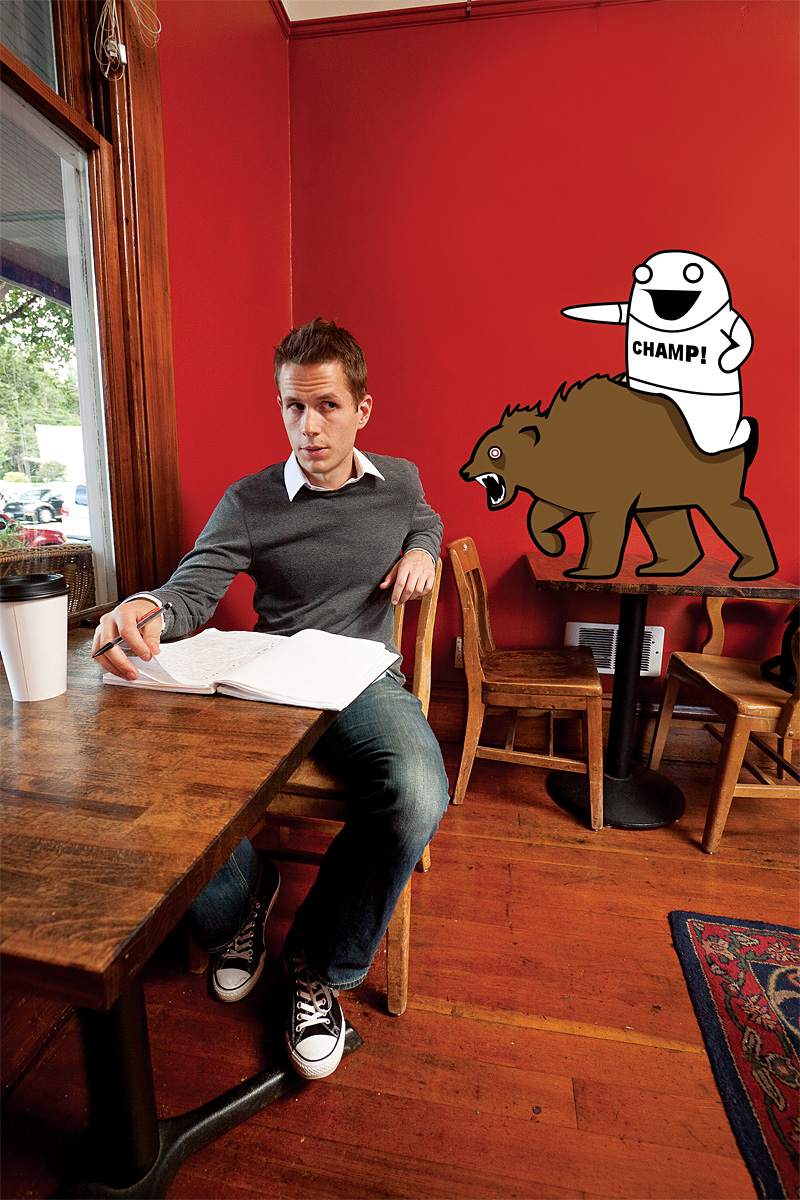

The Fremont Coffee Company is nearly empty, with just enough customers trickling in to keep up the whir of coffee grinders and the watery whine of steam wands. Amid this backdrop of Seattle white noise, Matthew Inman, creator of the wildly successful Web comic The Oatmeal, sits by the window.

With a few clicks and drags of the wireless mouse next to his MacBook Pro, a circle forms on his screen. Two more clicks, and two smaller orbs appear, creating the signature blank, vacant stare of his characters. Then a flurry of clicks, and a jagged mouth forms as the subject of the comic is jarred awake by an alarm clock emitting the following wake-up call: “BEEP BEEP SHRIEK fuckyou BEEP wakeupshithead BEEP BEEP BEEP HAHAHA BEEP fuckyoufuckyoufuckyou BEEP BEEP!” The time reads: “Ass O’Clock.”

On the keyboard, Inman is like Neo or The One. He knows all the Adobe shortcuts by heart and never touches a menu, his fingers flying across the board and commanding the program as easily as an artist dragging a pen across a pad.

This is Inman’s job. He isn’t a waiter/cartoonist or a barista/cartoonist or a housepainter/cartoonist. He’s not even a freelance computer geek/cartoonist. He stopped doing that work a year ago. Now, at 28, he draws comics, posts them to his website, sells merch, and turns a serious profit. He often works from home, or occasionally stations himself here or at Caffé Ladro across the street.

Inman enjoys working from home, he says. But, he adds, “Now I’m at the point where I’d like a little more social interaction with a co-worker. Talking to your dogs all day and being in your house, you kind of go crazy.”

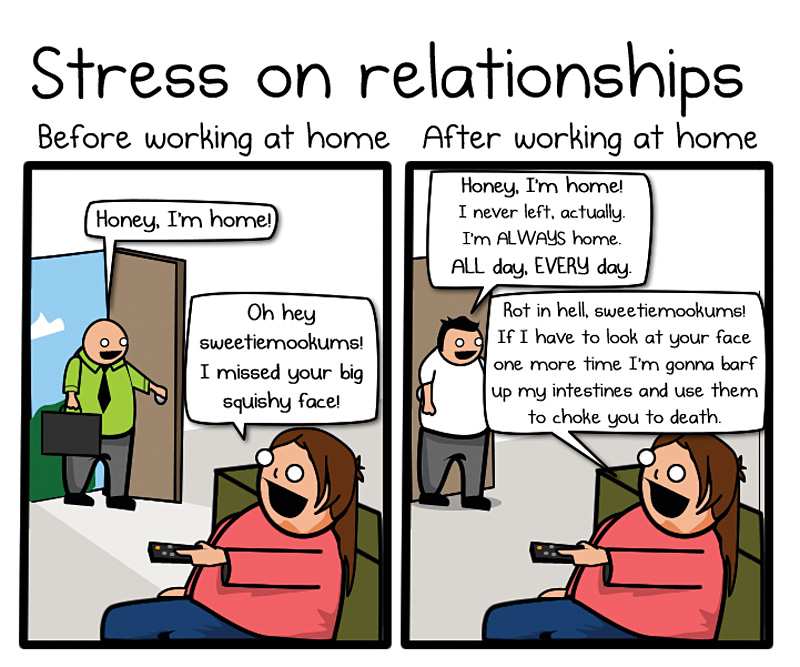

And that’s exactly the theme of the comic he’s in the midst of creating: “Why Working From Home Is Both Awesome and Horrible”—a strip that will eventually be shared by 62,000 Facebook users, retweeted 10,000 times, and enjoyably stumbled upon more than 100,000 times. In it, he first goes through the “awesome” parts of working from home, with a series of panels that don’t, in fact, show the awesomeness of anything (that would be very unlike The Oatmeal), but instead depict the miseries of office life—namely, interruptions by inane co-workers, acres of cubicles, and endless hours in the car (“Bad news, commuters!” says the radio. “I-5 is backed up for thirty miles due to rubberneckers staring at a couple of pigeons having sex on the guard rail.”).

From the horrors of the office, he turns to the horrors of the home office, with a series of panels showing the degradation of social skills, the Internet distractions (hey, it’s a video of a gassy goat!), and the loneliness (the last panel has a fat guy sobbing alone at his in-home water cooler). In another panel, a man walks in the door saying “Honey, I’m home! I never left, actually. I’m ALWAYS home. ALL day, EVERY day.” “Rot in hell, sweetiemookums!” she shouts back.

With this sort of cleverly crude and cathartic material, Inman attracts 4.6 million unique visitors to his site every month. And unlike so many Web operators, he’s even able to extract money from them.

Inman didn’t know how much he was making until a few weeks ago, when he sat down and did some tallying for the Weekly. He estimates his take-home pay for 2010 will be just over a half-million dollars.

Where a pre-Internet cartoonist like Seattle’s Gary Larson (one of Inman’s heroes) had to wait for a newspaper or syndicate to pick him up in order to gain a wide audience, the Web is allowing creative individuals to become fantastically popular with no middleman. It doesn’t, however, generally allow them to become wealthy. Or even to support a family. A 2008 New York Times article guesstimated there were fewer than two dozen Web comic artists able to make a living from their craft. Inman—whose ghoulish-nerd sensibility and obsession with animals is somewhat reminiscent of Larson—is a recent addition to that list.

To fully understand how The Oatmeal became financially viable, you have to understand a little bit about where Inman came from. Born in Southern California, he moved at age 7 with his family to Hayden Lake, Idaho, a town with a current population of about 500.

Matthew and his older brother Bryce used to wear matching lime-green Brontosaurus costumes with floppy brown spikes on the back, their heads poking through what should have been the dinosaur’s mouth. Sometimes they would roll a layer of butcher paper across the floor. Then, armed with black and red pens, they would draw a grisly war scene with stick figures.

“People just killing each other in every possible death you can imagine,” Inman recalls. “The red was for blood, because it was the most fun to draw. And then, to compound the weirdness, whenever wartime happened, we had to wear the dinosaur costumes.”

His first love was art. But when his family got a computer, Inman became hooked on gaming and programming. By high school, he was earning $8 an hour as a programmer at a local ISP. He never had to flip a burger.

He skipped college because, as he puts it, going to college meant being broke and learning programming languages that were a decade old already. Instead, he moved to Seattle to become part of the dot-com boom. His employers included SAGEPort, which built Web portals for senior citizens, and Neo Informatics, which created interactive online databases. Both were venture-funded and laid off all their employees after the stock market crashed, Inman says.

In 2003, Inman and two others co-founded the search-marketing firm SEOmoz.org. There he developed the search-engine optimization tools that would be both his triumph and his (temporary) undoing.

One of the common ways Google ranks a site in search results is by counting how many web pages link to it, and whether the link is on the relevant search term. So, for instance, if Google’s bots are scouring the Internet for the term “free online dating” and they see that thousands of sites mentioning “free online dating” link on that phrase to, say, Mingle2.com, that drives up Mingle2.com‘s ranking for that search term.

But how to get more web pages to link to yours? And how to have those links anchored to the desired search term? Inman fastened on the idea of quizzes. You’ve certainly seen them on Facebook, though Inman was working this technique before Facebook became popular. When you’re done taking a quiz, you get a piece of code, called a widget or badge, to post on your blog or profile. Generally, these widgets have a link embedded in them. But Inman decided to insert a little keyword or phrase too.

So let’s say you take the quiz “How Many People Have You Slept With? Too many? Too few?” and you get a pretty badge that says “You have slept with 4 less people than the average 23-year-old male.” You’re a virtuous sort of fellow and love that result, so you post it on your blog or (five years ago) your MySpace page. All your friends love the quiz and take it too, and suddenly hundreds of thousands of people have taken the quiz and gotten this badge.

But what you don’t see—and Google does—is the keyword or phrase that’s embedded in your badge, along with a link. And when Google sees hundreds of thousands of pages linking to, say, Mingle2.com, on the keywords “free online dating,” Mingle2.com is more likely to be ranked in Google’s first page of results.

After developing these tricks at SEOmoz.org, Inman went on to found, yes, Mingle2.com, a free online dating site, in early 2007. There he made dating-related quizzes, like the one above, that got big on social-networking sites. Sign-ups went through the roof. Inman eventually sold the site, but stayed on to keep making the quizzes.

Then in 2008, Britain’s The Guardian published a story about Inman’s technique, describing the quizzes as spreading “across the Internet like influenza.” Inman says the Guardian article made him look like “I was this virus author out to get your children.”

Google wasn’t happy, either. When the company’s monitors discovered what was going on, they kicked Mingle2 off the search page.

“Google looked at it and was, like, ‘Fuck that, goodbye,'” Inman says. “They just don’t like people manipulating the results.” Until the spat was resolved in June 2008, you couldn’t even find the site through Google.

After all that, Inman decided he wanted to run a website that would make it on its own merits.

His quizzes were funny and popular, and he’d dabbled in a few comics (like “Types of Bad Kisses”), so he started The Oatmeal in July 2009. He developed a rabid following by posting links to his comics on Facebook and Twitter.

And he hasn’t lost his knack for SEO (though these days he says he comes by it more honestly). As a result, when you search the word “oatmeal” today, Inman’s site ranks above both Quaker Oats and the Wikipedia article on oatmeal. Also, a section of his site satirizes the quizzes he once specialized in, with such multiple-choice offerings as “How Many Germs Live on Your Cell Phone?” and “Are Your Loved Ones Plotting to Eat You?”

Whatever you do, don’t call what Inman does a business. The word is offensive to the man who creates comics like “How to Name an Abortion Clinic,” which shows a doctor at his computer brainstorming options such as AbortMart and Magic Disappearing Fetus. (The winner: BIRTH CTRL+Z.)

Still, like it or not, a business is what he’s created.

As The Oatmeal became more and more popular last year, the fees he was charged to host the site went from $150 a month to several thousand dollars a month because of all the bandwidth demands. He was using a hosting company that sold ad space on his site, then cut him a check based on the number of people who clicked through. It paid so little he referred to it as “Webmaster welfare,” and even now, advertising accounts for only about 10 to 15 percent of his income. The site was actually losing money.

So in October, when the bill spiked, he decided to put up a PayPal donation button with a simple message: “Like The Oatmeal? It’s a one-man operation, so buy me a cup of coffee.” And suddenly the money started pouring in.

“That was pretty amazing for a while,” Inman says. “I was making hundreds of dollars a day. I had a couple $500 days. I wasn’t delivering a product other than my comic.”

He raised more money than he needed to cover the bandwidth fees, so he used the extra to self-publish a book, called 5 Very Good Reasons to Punch a Dolphin in the Mouth. That too did well, and he began making daily trips to the post office to mail the hand-addressed packages—which at first seemed romantic but, in practice, was becoming tiresome. So The Oatmeal‘s mom stepped in.

“I told him, ‘Honey, why don’t you let me do this?’,” recalls Ann Inman. A longtime artist herself (she says the family’s ancestors painted European church frescoes), she also had experience in shipping and receiving. She took over that end of his business, mailing The Oatmeal products from the tiny town of Rockport, about two hours northeast of Seattle.

“The postmaster told my mom that the amount of mail went up 700 percent because of me,” Inman says. “It’s a good deal. It gives [Ann and her boyfriend] a job, and allows me to have someone I can trust doing shipping and receiving and customer service.”

He began expanding the merchandise, using a print-on-demand service from Zazzle.com. But there were two big problems. First, Oatmeal comics aren’t small or uniform in size, so printing them on, say, a poster, T-shirt, or coffee mug can make them look really crappy. Second, the profit margins were god-awful because Zazzle basically makes products one at a time, as ordered, which is very expensive. Posters are the best example. After selling 1,000 posters at $12 apiece—$12,000 gross—Inman got a check from Zazzle for $300.

But success breeds success, and that’s how it worked for Inman. Eventually, he became confident enough of future orders to buy merchandise in bulk in advance. His posters are now printed at Savage Color, just a few blocks from his house, and at Windward Press in Greenwood. Instead of customers choosing the comics they want, Inman chooses which strips, or individual panels, will work best on posters. And by buying in volume and stocking his own inventory, he pays just $1.50 for each poster. So now when he sells 1,000 posters, he gets to keep $10,500 instead of $300.

Like many a small-business owner who has dipped a toe into Groupon, Inman has also learned the power of a discount. For The Oatmeal‘s first anniversary, he had a half-off sale, expecting maybe two or three times the normal amount of orders. That one day, the store did $25,000 worth of business, 10 times the average. He had to call in his cousins to help process the orders, and it took weeks to catch up.

It’s a good thing he can whip out a comic in a few hours, once an idea is formed. He has to spend the rest of his day dealing with inventory management and other entrepreneurial issues.

“I feel like I’m being pulled in 15 different directions, and no one can do any of these things but me, because I’m the only person with all the keys,” Inman says, adding that he’d love to hire a graphic designer and a business manager/personal assistant. “I’m totally opposed to making this a company. I just don’t have it in me. But I do need help with some of these things.”

Meantime, another income stream is on the way: Like so many other Web sensations, Inman got a major book contract. In March, his first non-self-published book will be released by Andrews McMeel Publishing—the giant behind Calvin and Hobbes, The Far Side, and Dilbert, to name a few. The first run will be about 30,000 copies, and he’ll go on a West Coast book-signing tour.

No iPhone app yet, but he’s working on it.

Dig around on The Oatmeal‘s site long enough and you’ll find a self-portrait of the cartoonist. His head is vaguely potato-shaped, he has two tufts of brown hair poking off to the sides like Krusty the Clown, and he has a lazy eye. He’s wearing a party hat; “The Oatmeal always wears a party hat,” the site says, “because he’s always in the mood to party.”

The man sitting in the coffee shop sipping an Americano with Splenda couldn’t be farther from the image. He’s thin and trim, keeps his hair short, and, sadly, isn’t wearing a party hat. He’s animated when he speaks, and has a tendency to go off on tangents that sound suspiciously like potential Oatmeal comics.

He considers himself obsessive-compulsive. A typical Sunday consists of a hard workout, followed by housecleaning. (He lives in a townhouse.) Then, as a reward, he might watch a movie or dork around.

He snowboards, and is in love with endurance sports: Last year he completed a half-Ironman competition, and plans to do a full Ironman before he’s 30. After he sold Mingle2.com, he took a trip to Japan, and has since been learning to speak Japanese (he’s conversant but not fluent). He’s daydreamed of moving to Thailand.

“I like Seattle, I like the people, the coffee, the culture,” Inman says. “But I absolutely hate the weather. I’ve bitched about it for 10 years. This weather”—he points to the gray sky outside—”this exact weather is what drives me crazy.”

The Web has become an especially important outlet for comic artists as many newspapers, hurt by the rise of the Web, have cut back on space for comics; some, such as The Washington Times, have completely eliminated them. The syndicated comics that remain often are meant for the traditional newspaper demographic, meaning families with children and seniors. Which means that, with a few exceptions, they tend to be clean and appeal to the broadest audience.

The Web has allowed the flowering of a new approach. Many artists, like Inman, regularly use language they couldn’t possibly get away with in a daily newspaper. And not just four-letter words. The humor in the hugely popular Web comic xkcd, for instance, draws on math, language, relationships, and computer programming. It will occasionally delve into sex in explicit detail (admittedly drawn with stick figures). And many comics, like Seattle’s Penny Arcade, cater to a certain demographic that loves the Internet but shies away from print papers: geeks and gamers and that crowd.

Of course, these are the successful ones. As in every other field online, there’s a sea of comic artists, most laboring in (sometimes deserved) obscurity. “Unfortunately, with many online comics, it’s clunker, clunker, clunker, then a good one,” says Patty Rice, Inman’s editor at Andrews McMeel. “They’re just not consistent.”

Rice first came upon Inman’s work when she saw “17 Things Worth Knowing About Your Cat” linked on someone’s Twitter feed. She began browsing his site, finding comic after comic funny. So she printed a handful and showed them to the acquisitions board.

“This is one where, hands-down, everyone around the table loved it,” Rice says. “It’s just really strong and original humor. I really do think it’s his own original voice.”

Yet even a cartoonist near the top of the heap, like Inman, still sees room for improvement. “The past couple months I’ve become very frustrated with the [visual] style I use, because it’s very repetitive,” he says. Since Inman draws with a mouse, all the lines in his comic have the exact same width. In short, they look like they were drawn on a computer, not by hand. And while he thinks his comic will still be drawn on a computer six months from now, he may switch to something like a tablet and a pen to make it look less robotic. This summer, he took a comic-drawing class at the UW.

“I look at other comic artists, and I see all these things they do that I cannot do because I draw with a mouse. It lacks that human look to it.”

Inman is a fan of The Perry Bible Fellowship, and of xkcd, which he especially envies because the art is so much simpler. “I do envy Randall Munroe [creator of xkcd], because his are all stick figures, so he gets to focus all his energy into the dialogue and not have to sit there drawing a raccoon trying to bite the wheels of a tractor. You know how long that takes? Tractors have lots of parts, and so do raccoons. This guy draws stick figures. No wonder he puts out a comic a day.” Inman publishes more like one or two a week.

Gary Kurtz was a producer on the first two Star Wars movies. He later had a falling-out with George Lucas. Last month, he appeared at a Star Wars convention in Orlando, Fla.

He told the Los Angeles Times in an interview that the third Star Wars movie, Return of the Jedi, was originally going to end on a bigger downer, with a scattered and damaged rebellion, Leia facing difficult new duties, Han Solo dead, and Luke walking off alone. Lucas, though, made the decision that none of the principals would be killed, and that the movie would end with an Ewok celebration described by the Times as “a teddy-bear luau.”

The reason, according to Kurtz? Lucas didn’t want to jeopardize the merchandising potential.

“The emphasis on the toys, it’s like the cart driving the horse,” Kurtz told the Times. “If it wasn’t for that, the films would be done for their own merits. The creative team wouldn’t be looking over their shoulder all the time.”

This could be a cautionary tale.

Inman loves the profit margin on his posters. And that people like to buy posters of his comics that express outrage at bad grammar. (Inman may have skipped college, but he’s got an English professor’s fastidiousness about language.) One comic that sells particularly well as a poster is “Ten Words You Need to Stop Misspelling.” It addresses, for instance, the proper usage of “there,” “their,” and “they’re.” The way he conveys it on the poster, though, is not exactly how you’d be instructed in Freshman Comp. “If you put an A in ‘definitely,'” says one panel, “you’re definitely an A-hole.”

Inman intends to rewrite that poster so it’s more family-friendly. “I’m going to do it, probably before Christmas,” he says. Why? Schools love them. Normally, if he makes a comic and it’s funny, the poster will sell—but only while the comic is new and fresh and getting tons of traffic. His grammar posters, though, sell long after the initial traffic wears off. He’s actually paying someone now to do the research for a poster about how to properly use a comma.

Is there a danger? A fear of selling out for the sake of moving merchandise?

“Yeah, a little bit,” he admits. “I don’t want to say, ‘Oh, I’m going to make a comic about this because it’ll sell.’ But then again, I also need to make a living.”