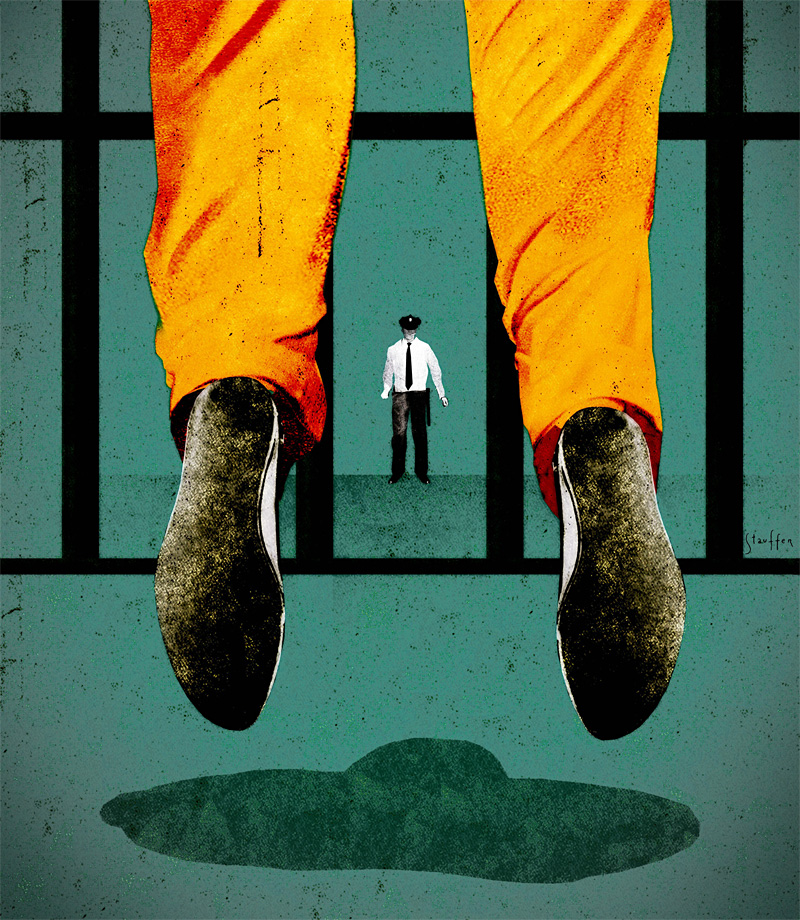

Franklin Antill prepared for his death much more skillfully than he had lived his life. At 36, the shaved-headed, raccoon-eyed Everett laborer already had convictions for kidnapping, assault on a police officer, and burglary. On this day, July 3, 2009, he was in the 1,700-bed downtown King County jail for the knifepoint rape of a Wallingford mother, having been arrested soon after he had attempted to use her credit card at a Lynnwood Walmart.

With his already lengthy record, Antill was facing a possible life sentence, and wasn’t exactly winning any hearts during his ongoing rape trial. Acting as his own attorney, he had aggressively grilled the mother on the witness stand, trying to get her to admit he was some sort of “love doctor” with whom she’d had an affair. That was untrue, she said; she’d never met Antill before the October 2008 assault. In a few days, it would be Antill’s turn on the stand. Prosecutors would have the opportunity to grill him in return.

Instead, Antill was about to use the evidence against him to help kill himself off. Literally. As a pro se attorney, he was allowed under state law to store charging papers, witnesses’ statements, and other documents needed to prepare his defense in his cell. Sometime after midnight, he began moving the boxes around.

He tore up some of them and wedged the cardboard pieces under his cell door, along the rail it slides on. Then he fashioned a makeshift doorstop device, rolling up paper, cardboard, and bedsheets into a solid wad to prevent the door from opening. He ripped his sheet into strips, made a noose, and threaded it through an overhead light fixture he had partially pried from the ceiling. Then he tied the noose around his neck and stepped off his bunk into eternity.

Around 2:30 on the morning before Independence Day, corrections officer Daryl Harris, making his hourly security check, walked past Antill’s cell on the 11th floor of the quarter-century-old jail and saw the inmate hanging motionlessly from the fixture. When Harris tried to open the door from a control panel, the door jammed. Officers flooded the scene. They used a T-bar to pry at the door, and employed a rescue knife on the locking mechanism. After several minutes, they had moved the door enough to squeeze in and begin lifesaving efforts. Fire Department medics arrived within 10 minutes, worked on Antill five more minutes, then declared him dead.

There was little doubt it was suicide, as the medical examiner later officially ruled. And thanks to Antill’s fortification of his cell door, he delayed rescue attempts by almost five minutes. According to jail records, Antill had told a jail nurse the previous year that he’d considered suicide in the past, but not since; thus he wasn’t on suicide watch.

Still—ripping up a sheet and hanging oneself? The jail won’t say exactly how he was able to work the noose through the overhead light fixture. But that sounds like a golden oldie, something out of a 1940s prison movie, and it occurred in a jail that just six months earlier had been put under federal oversight to prevent such deaths.

Only now is that threat being fixed, the county says. “The department is working on reducing the risk of self-harm by grouting the light fixtures attached to the cell ceiling,” says jail spokesperson Maj. William Hayes. “The grouting helps close up the very small gap between the light fixture and the ceiling,” Hayes says, adding that the project has already been completed in the jail’s “psych areas,” where mentally ill prisoners are housed.

Under a 2009 legal agreement with the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), the county is required to improve operations at the jail—a cluster of blocky mid-rise towers just west of I-5, across from Seattle City Hall. Certain standards at the downtown lockup must be met during a three-year federal monitoring program established under an agreement with the DOJ. Failure could mean further court action, such as monetary penalties against the already cash-strapped county.

The deal evolved from a 2007 DOJ investigation that found jail safety and health conditions so substandard that they constituted violations of inmate civil rights. Along with “preventable” deaths, probers found that inmate abuse was “routine” and jail operations had “serious” deficiencies—some of them taking place right before investigators’ eyes. An inmate on suicide watch somehow obtained and swallowed multiple medications while DOJ officials were on the same floor. They watched as security staff failed to call for medical help for a crucial eight minutes. It took another seven minutes before a nurse arrived with a medical crash cart, and 25 minutes after the suicide attempt for fire department medics to arrive. Though the inmate survived, the DOJ called it a “life-threatening example” of the jail’s failure, leaving inmates at “grave risk of harm.”

The county’s smaller, 1,300-bed jail at the newer Maleng Regional Justice Center in Kent has been running more smoothly.

The DOJ said it began its probe in the wake of news reports, citing KING-TV reports on an outbreak of MRSA, the sometimes-life-threatening bacteria that plagues jails and prisons, and Seattle Weekly stories from 2005–2007 on preventable suicides and medical errors. The DOJ said there were at least five preventable deaths at the jail during those years, even though the jail population was dropping. Among them was a hapless gas-station robber named Ronald Hicks, 43, who ran out of gas during his getaway. He was so despondent about his mostly small-time crimes that he once asked a court to kill him (“Hook me up to something and let me go. Don’t make me wait to die”). He did the deed himself, hoarding his prescribed jail sedatives until he had enough for a fatal overdose.

Another despondent inmate, Sabrina Owens, 36, who had caused a horrific auto accident in a stolen truck, hanged herself while alone in a holding cell using an easily accessible six-foot power cord from a wall-mounted TV set. Also, Wade Scott Brown, 50, who had been having psychotic episodes, died officially from a heart attack, although a wad of medical gauze was found stuffed in his throat.

The three-year federal agreement specifically requires the county to protect inmates from any further self-harm and from being harmed by jail staff. It also requires the county to provide proper medical care: Medical errors soared mid-decade, with at least two prisoners dying from jail-related illness—one of them from necrotizing fasciitis, known as flesh-eating disease.

To make sure the jail complies with the agreement, the DOJ appointed three jail experts to monitor progress and issue quarterly reports.

“The monitors,” says jail spokesperson Hayes, “have consistently praised the county’s cooperation and described many of the county’s practices as models or best practices.”

Lead monitor Lindsay Hayes, a national expert on penal conditions and jail suicides (and no relation to the jail spokesperson), says he can’t confirm or deny that claim. The court agreement between the DOJ and King County prevents him from commenting on jail conditions or whether the jail is living up to the settlement. “The team’s opinion about the county’s progress is clearly stated in the reports,” he says.

According to Hayes’ most recent report, issued in May, the county is fully compliant with only 15 of the 35 conditions agreed to under the settlement. The low score is due partly to the time required to institute the reforms, the report indicates. For example, the jail is changing its policies on the use of restraint chairs and boards, and on pepper spray, whose misuse DOJ investigators blamed for the widespread abuse of prisoners (pepper-spraying mentally ill inmates was a common practice, and the DOJ frowned especially on hair-holds used to manage and discipline inmates). Those new policies are still evolving into full compliance, Hayes says in the report.

On the plus side, Hayes notes that the county has at least been making “steady progress” since 2009. In general, environmental-health conditions and medical-care quality have substantially improved with changes to operations and staffing, he says.

But not all the signs are good. Though the facility had averaged just one inmate death per year from 2000–2002, it has averaged more than five per year since—the majority of them from natural causes, among a jail population that typically includes alcoholics and drug addicts in poor health. Those who died on the jail’s watch last year include Joseph Demmert, 27, who was arrested on a warrant and died a day later from a skull fracture. The medical examiner said the fracture happened prior to Demmert’s arrest, while he was intoxicated, though the injury went undetected during the jail’s intake process, when inmates are screened for physical and mental health problems.

At the time Lindsay Hayes issued his May report, there had not been a single jail death in 2010. But on August 16, an inmate was found swinging in his cell. Officials are still investigating and have so far released few details (though the medical examiner has ruled the death a suicide). The deceased was identified as Christopher Goldner, 32, who was being held for second-degree assault.

Ten days after Goldner’s death, a second inmate, Ronald Smail, 55, also died, apparently from natural causes, the jail says. He’d been booked into the jail on a warrant from Kittitas County, then transferred to the county correctional facility in Kent, where he became ill and was rushed to a hospital. The jail is still investigating that case as well.

“The jail has come a long way,” King County Executive Dow Constantine told Seattle Weekly, “but any death in custody is a tragedy. Given that many inmates come to the jail with serious medical and psychological conditions, it’s a daily challenge to protect their safety and health.” The county’s Department of Adult and Juvenile Detention (or DAJD), which oversees the jail, has had four directors in two years. It’s currently overseen by an interim chief, and Constantine says he will name a permanent replacement shortly.

Another county official, speaking off the record, says there is always the danger of inmates finding “some way” to kill themselves, despite precautions. “You can make a noose from whatever, attach it to something, and just lean or slump over ’til you pass out,” he says.

But Lindsay Hayes argues that such defeatist attitudes “often impede meaningful suicide prevention efforts,” as he wrote in a 2007 study.

Besides Antill’s suicide last year, there were five other “serious suicide attempts” by county inmates from August 2009 through March 2010, Hayes’ May report notes, though it doesn’t reveal anything about them.

Asked if the next monitor’s report, due out this month, would address Goldner’s recent suicide, Hayes declined to say. Nor would he say whether the report delves into a new and unexpected jail safety issue—the first riot in at least a decade.

The uprising began around 2 p.m. on Sunday, March 28, on the 10th floor dayroom, when an inmate, a career criminal named Larry Watkins, 51, got into an argument with a corrections officer and then refused to return to his cell. Watkins allegedly pulled a shank and made threatening gestures, according to a confidential county report and court records. Then other inmates jumped in to back Watkins, and the jail tank erupted.

A follow-up investigative report, written by Hikari Tamura, interim director of the county’s DAJD, details how 18 inmates barricaded themselves inside C tank and began destroying the unit, hanging sheets to partially obscure their actions. Corrections officers tried using pepper spray to control inmates, but had to back out to safety. Seattle police were called to set up an outside security perimeter, and King County deputies in riot gear assembled to rush the tank.

It turned serious enough—besides the shank, inmates had a metal battering ram, which they used—that officers were given the green light to shoot to kill if necessary.

In a (partially redacted) report filed two days after the incident, jail Maj. Corinna Hyatt said an officer had asked her “why our staff did not have less than lethal options available. I told him that in previous years there had been proposals submitted [for such options]…but the proposals had not been supported by the Executive’s Office [i.e., former King County Executive Ron Sims, now serving in the Obama administration] for unknown reasons.”

Such options (their exact descriptions were excised from the report for security reasons) are now being reconsidered. Sims’ successor Constantine says he will seek funding for more protective gear, and supports the use of less-than-lethal options such as stun guns.

Hyatt, a top commander, made a post-riot inspection of the damage, and “observed flooding, shattered dayroom windows, torn bedding, mattresses, broken fixtures…the tank was trashed.” The loss was estimated at $13,000 as a result of what was thought to be the first such riot in 10 years, according to Tamura’s report (though no one could specifically recall a comparable incident).

Watkins was charged with instigating the riot, felony harassment, and malicious mischief. He’s familiar with the surroundings he’s accused of trashing: His record includes nine felony convictions for robbery, drug violations, assault, and other crimes. Court records show that 50 warrants have been issued for him over the years, and since 1998 he has been booked into the county jail 41 times.

The public likely has little sympathy for professional criminals such as Watkins or those with records like Antill’s, and their jail living conditions typically don’t get much media attention. The DOJ settlement, however, has helped the county refocus on what jail spokesperson Hayes calls “our commitment to operating safe, secure, and humane detention facilities.”

The 2009 agreement followed the retirement of then-jail director Reed Holtgeerts, and came in the wake of another questionable death during the Sims administration. Karen Jane Matthew, 51, arrested for selling rock cocaine on Aurora Avenue in September 2008, experienced 30 raucous hours of imprisonment, during which she lost consciousness and split open her head in a fall; told a cellmate she was “dope sick” and had lost control of some bodily functions; drank from a cup of dangerous jail chemical disinfectant left in her cell; and vomited and made gagging sounds throughout the night. She was found dead the day after she was booked. Even after admitting that Matthew might not even have been searched for drugs during booking, the jail said it had not changed any of its procedures.

Today there is change, says Maj. Hayes, both at the downtown jail and at the county’s lockup in Kent. Together the two facilities booked almost 45,000 inmates last year—a “medically complex and challenging population [with] acute and chronic health needs,” as Hayes observes. As of this year, the jail has instituted a more intense intake process to screen injured and mentally ill inmates, he notes. Use-of-force practices have changed—hair-holding to restrain inmates has been discontinued, for example—while case management has improved, leading to better tracking of individual inmates’ medical and mental-health care.

Compared to earlier years, “Our suicide rate remains low and we continue to work hard at increasing safety of our inmates who are at risk of self-harm or suicide,” he says. For the most part, physical suicide enablers, such as electrical cords, have been removed. There are now daily mental-health assessments of inmates on suicide watch, Hayes says.

In his report, monitor Lindsay Hayes seems less enthusiastic, pronouncing the reforms “adequate” and calling other issues “problematic.” He cites as an example the case of an inmate who admitted he had earlier attempted suicide, but who was not referred to the jail’s psychiatric intake unit. He was finally referred a month later—after he’d attempted suicide again.

Hayes was troubled by another incident during a a recent onsite visit (Hayes lives in Massachusetts). He recounts in his report that, during a discussion with the jail treatment team about a prisoner in “acute isolation,” the team was concerned that the inmate’s mental health was deteriorating.

Hayes asked why the inmate couldn’t be moved to “sub-acute” housing, which allows up to six hours of out-of-cell time per day instead of one. The response, Hayes reports, was that inmates in the “sub-acute” units “were not allowed to be on suicide precautions.”

Hayes writes that “it was the first time [I] had heard of such a practice. It makes little sense.” The jail promised to “look at” what could be done.

Protecting inmates from harm includes protecting them from mistreatment by jail staff, and the county facility is not fully compliant in that area either, says another member of the three-man monitoring team, jail consultant William Collins, a former Washington state senior assistant attorney general. The jail staff is doing a better job of applying force appropriately, he says. The use of restraint boards and chemicals such as pepper spray has decreased, he reports—particularly against mentally ill inmates. But he questioned the use of restraint chairs in some cases, and said use-of-force training needs improvement. In addition, the jail’s investigation and reporting of incidents involving force is still suspect, he found.

The jail does seem to be making advances in the battle against diseases, however, says Dr. Ronald Shansky, former medical director of Illinois prisons and the third member of the federal monitoring team. King County, so far, is complying with medical standards to maintain an “adequate” jail atmosphere, he reports, and housing units “in general” are “well maintained.” There were rare instances of plumbing problems, such as leaks, he said, and on his latest tour he didn’t find any mattresses that appeared to be significantly damaged or soiled. Hygiene was maintained at appropriate levels, he determined, and incidents of MRSA seemed contained. “Overall, the program of identifying and responding to skin infections appears to be effective,” Shansky says.

Monitoring of the jail can continue into 2012, and if the facility is not fully compliant to the DOJ’s satisfaction, the feds can return to court and seek further relief. Obviously, the county wants to avoid more extensive penalties, including costly fines. King County expects a $60 million budget gap next year, but, helpfully, overall jail costs have been decreasing due to its population decline. As well, Seattle and some suburban cities recently signed a new jail agreement with the county that is expected to add $900,000 more in revenue. Meanwhile, seven south-county cities are building a jail slated to open next year in Burien, taking pressure off the county system.

“I have asked DAJD and Jail Health to build on their progress,” says a hopeful Constantine, “and continually review their systems with a critical eye to all practices involving inmate care.” The county’s working to make jail a nicer place to visit, he says, “and the Justice Department has taken note.”