“In Chicago, at a signing I get like 10 people. In Seattle, it’s like 2,000.” So says cartoonist Dan Clowes in the 1994 documentary Hooked on Comix, Vol. 1. The film will be screening on continuous loop in the Olympic Room this weekend, part of an exhibit organized by Fantagraphics Books called “Counterculture Comix: A 30-Year Survey of Seattle Alternative Cartoonists.”

As much as for coffee or indie rock, Seattle has long been a national center for creative, and cynical, cartooning. Even before the grunge boom helped artists like Peter Bagge, Jim Woodring, and Pat Moriarty gain national exposure, there was a late-’60s flowering of the form—the Northwest children of Robert Crumb, if you will.

Larry Reid, who joined Fantagraphics in 1992 and today runs its bookstore/gallery in Georgetown, cites the example of the late Walt Crowley, who, before becoming a prominent journalist and historian, was a cartoonist at The Helix, which published from 1967–70. Why did Crowley eventually trade his pen for a typewriter? “He was a great artist,” says Reid, “but he wasn’t fast enough.”

By contrast, a prolific powerhouse trio emerged from The Evergreen State College in the late ’70s: Charles Burns (whose acclaimed graphic novel Black Hole was inspired by his teen years at Roosevelt High School), Matt Groening (future creator of The Simpsons), and Lynda Barry (perhaps best known for her 1988 novel The Good Times Are Killing Me, later made into a musical play).

The Bumbershoot show covers a period beginning in 1980, when, Reid recalls, “a cartoonist could live on air. I graduated from college and opened an art gallery in Pioneer Square. Kids can’t do that now.” (Well, maybe not in Pioneer Square, but kids are opening them elsewhere.) At that time, Burns and Groening had left the Northwest, but were contributing from afar. Groening’s soon-to-be-famous strip Life in Hell ran in The Rocket. Burns’ work in the Art Spiegelman magazine RAW led to Fantagraphics publishing his Big Baby and other titles.

But it was Barry who became the city’s alt-comics star. She began a regular strip, Ernie Pook’s Comeek, in Seattle Weekly in 1986. And her first books, collecting that strip and others, were published by Real Comet Press, run by Comet Tavern owner Cathy Hillenbrand. Her Poodle With a Mohawk poster became a snarling local icon during the Reagan/Angry Housewives era.

Barry left Seattle in 1989 but continues her art; her latest graphic novel, What It Is, recently won an Eisner Award. After looking back through his archives—and Fantagraphics’ and some private collections—Reid declares, “The biggest surprise is how well Lynda Barry’s stuff stands up…not cute or trivial or girly.” (Poodle and many other of her works will be on display this weekend.)

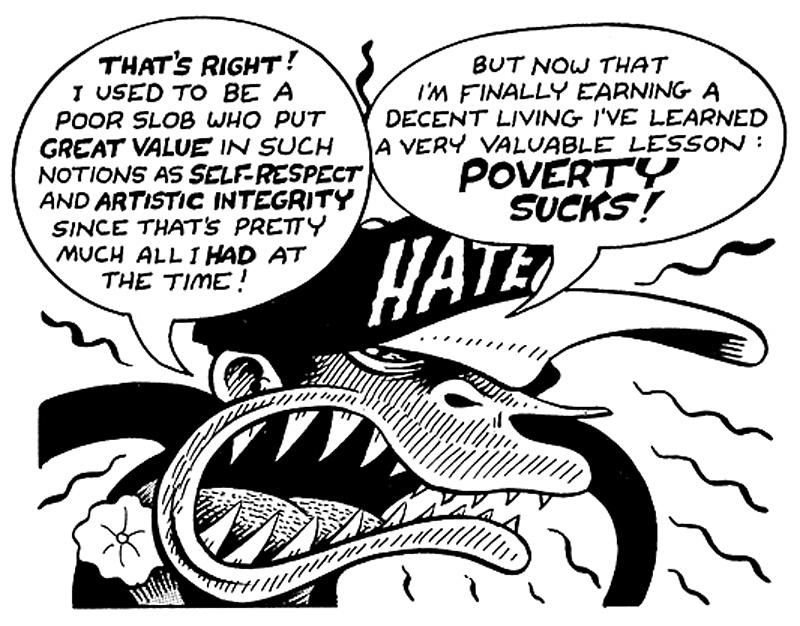

Then came grunge. Peter Bagge recalls with a chuckle in Hooked on Comix that “I’ve been able to ride on the city’s coattails.” He’s being too modest, of course: His bitter, wayward rocker-wannabe character Buddy in Hate is almost as much a grunge icon as Kurt Cobain. (The exhibit’s wall text quotes a 1992 Seattle Weekly story by Bruce Barcott that said: “Twenty years from now, when people want to know what it was like to be young in 1990s Seattle, the only record we’ll have is Peter Bagge’s Hate.”)

Bagge was among many local cartoonists employed by Sub Pop and other labels to do posters and album covers for suddenly national bands. The exposure helped everyone, Fantagraphics included. “The counterculture reached a critical mass,” recalls Reid, who lauds “how integrated those disciples were—comix, music, and graphics” during that boom. “Cartoonists not just satirized or documented, but really informed the grunge movement.”

Nearly 20 years later, the productive collision of Seattle’s graphic-arts and music scenes can still be seen on any light post or telephone pole on Capitol Hill. From the younger generation, work by Megan Kelso (Artichoke Tales) and Ellen Forney (I Love Led Zeppelin) will also be on view, along with some 300 drawings, artworks, and posters.

And lest you dread squinting at tiny wall panels, Reid promises “posters and paintings—not just little stuff.”

Several artists will be on hand, including David Lasky, whose Bureau of Drawers collective will provide cartooning demonstrations and instruction (as will Friends of the Nib). Vol. 2 of the Hooked on Comix documentary series, made in 2002, will also be screened; and director Moore will attend to show his in-progress Vol. 3.

Unlike at Flatstock, however, nothing will be for sale.