Niilartey De Osu walks into his studio and toward his tools. He’s soon holding a pair of cutting shears in one hand and a dish filled with clothing pins in the other. He pauses a moment to visually measure the drab skirt and jacket he will soon transform, and moves in to make the first cut.

“You look like the person at the party that nobody wants to talk to,” he jokes to Richael Manisha Karter, the woman wearing the garments. It’s De Osu at his most comfortable, creating while gently teasing his muse: five feet 11 inches of ethnically ambiguous former model who grows more naked with every snip.

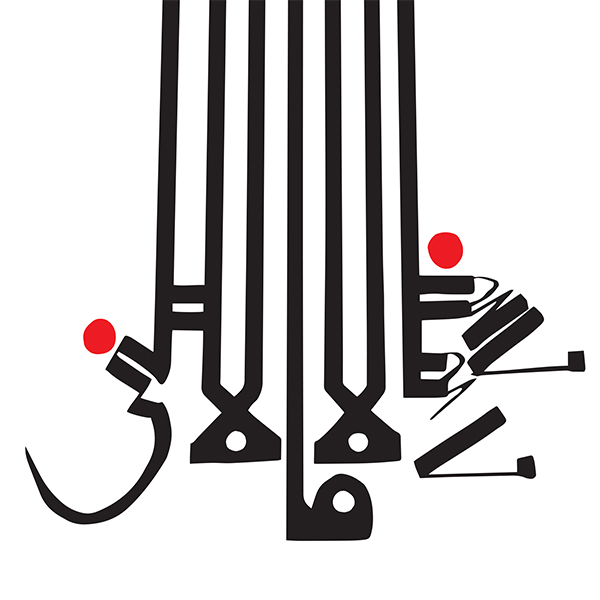

The converted art gallery De Osu is designing in serves as studio, showroom, and base of operations for Neodandi—the name not only of De Osu’s fashion line, but of a movement he hopes will spur a fashion renaissance in a town famous for its no-frills sensibility.

De Osu—44, handsome, short—stands eye to clavicle with a stiff-backed Karter in front of double full-length mirrors. The cutting continues, and wedges of fabric begin to pile at her feet. His goal for this afternoon is to create a woman’s jacket from the charcoal-grey two-piece ensemble one of his assistants secured from a local thrift store. As he describes it, it will fit as if it were just about to slip off the body. And as with many of De Osu’s designs, the end product will be a bit revealing.

Hung dramatically from a maze of pipes in the Neodandi showroom are men’s and women’s garments of various materials and types. There’s a slight military-uniform influence, as if he were designing for some post-apocalyptic officer who doesn’t mind texture and has little concern for consistent zipper placement. None of the designs, however, could exactly be described as understated. A prerequisite for becoming one of De Osu’s customers— Neodandis, as he calls them—would seem to be a lack of timidity.

De Osu looks every bit the stereotypical fashion eccentric in his own uniform: artfully ripped black trousers (which he designed himself), a flowing white button-down with unfastened French cuffs, and a turban. Nearby is Neodandi’s resident seamster, Lance Phromnopavong, also wearing a turban. Shortly after he began working at Neodandi, Phromnopavong told De Osu the story of his turban: A young girl gave it to him while he was waiting for a bus in Bangkok. Soft-spoken, lanky, and dressed in a flowing red suit coat, he’s worn it nearly every day since.

The two move in semi-tandem, with De Osu cutting here and fastening there as Phromnopavong hands him pins. In the parlance of the fashion design community, the technique is called deconstructing. It’s what De Osu specializes in: taking materials from different sources and tearing them down to build them back into something else. Unlike many designers, he doesn’t sketch his work beforehand; rather, he intuits the design. Like an improv comedian, he works without a net.

After a few minutes, the jacket starts to take shape. De Osu cuts another length of fabric from the skirt, then pauses a moment to wax metaphysical. The son of Ghanaian immigrants, De Osu speaks in an accent that is not quite African, just vaguely foreign. Fashion design, he explains, is about “energy that we can’t see but that we can synch with, energy that can turn two things that are mundane and bring them together to turn them into something beautiful. We can’t see it, but it exists.”

The fitting continues, as does the lecture. “Neo,” he says, shortening the name of his line, “is a perpetual state of birth. It’s the thing that never is because as soon as it comes out, it’s no longer what it was.”

In 2004, after struggling for years on the borders of Seattle’s arts scene, De Osu began to design apparel with material begged from local wedding shops. Six years later, he’s one of just a handful of local couture designers who have managed to gain a level of notoriety—though in his case, infamy is also an applicable term.

De Osu takes one last look before Karter heads to the back rooms to change back into her own clothes. From the first pinning to the last, the entire process took around 45 minutes. Afterward, she passes the jacket on to be “dissected and perfected” by the seamsters—one of whom will quit two weeks after Christmas, citing the repeated tardiness of her scheduled pay.

She’s not the only employee who’s quit Neodandi in frustration. Since he began designing, De Osu, who cannot sew a stitch, has been disgruntling the people he’s commissioned to do it for him. One former staffer who spoke on condition of anonymity says, “It’s like he’s a cult leader. He has people buy into the idea that Neodandi is not just a fashion line, but that it’s this grand way of life—and then he doesn’t pay them on time.” It’s not uncommon for Neodandi’s staff to put in 80 hours per week, she adds. Those who aren’t willing to do that, she continues, don’t last long.

But De Osu’s business-related missteps aren’t limited to personnel management. For a period he was rarely on time with rent, and he was sued for failing to make the deadline on a commissioned wedding dress. He’s also earned the eternal disdain of one former business partner who sank what she claims was more than $200,000 into Neodandi, a maneuver which bankrupted her.

De Osu admits he’s made mistakes. It’s just that he refuses to allow anything to shake him from the path he started on years ago, when he left his father’s Raleigh, N.C., home and birth name behind and became Niilartey De Osu.

But given that his focus on the creative sometimes comes at the expense of his professionalism, will Neodandi the concept eventually be the death of Neodandi the business? That’s a question for another day. Right now, racks need filling, work that won’t continue until Karter finishes her meet-and-greet with the potential patron who has just wandered in off the street.

De Osu gingerly peeks from behind the curtain that separates the showroom from the production space. For a guy who’s made it his job to coax people into outward displays of self-confidence, De Osu is, behind the Eastern mysticism and showy tailoring, painfully shy.

“Designing,” he says, “can be a terrifying experience.”

Seattle doesn’t so much have fashion circles as it does pockets of awareness. And among those who pay attention, De Osu’s work has been described as “slick” and “innovative.”

A May 2005 Seattle Post-Intelligencer review breathlessly described Neodandi’s multi-themed, 100-piece fashion show at the nightclub Trinity in Pioneer Square thus: “This is the look of an international street tribe—cool kids who don’t give a flip about fitting in (but can still swing $325 for a Reconfigured Denim Star Skirt).” Further legitimizing his enterprise, Neodandi scarves and other accessories are now being carried at the Seattle Art Museum’s retail shop. (For a few weeks in December, a linen Neodandi scarf and bag were displayed prominently in SAM’s front window.)

Renata Tatman, SAM’s chief buyer, says that after seeing De Osu’s work, she was immediately drawn by the “sculptural nature” of his designs. “He has perspective,” she says. “He has that raw creativity that you see in people who are thinking outside the parameters.”

Seattle is often characterized as a city without a fashion scene—the kind of town where people attend the opera in tennis shoes. “There just isn’t the culture to support a high-couture scene here,” says Joan Kelly, instructor of fashion marketing at the Art Institute of Seattle. “Seattle is too understated of a town. There are charity events where someone can wear high fashion, but is it couture? No.”

Thirty years ago, Seattle was anchored fashion-wise by department stores, says Dr. Robert Whaley, Instructor of Design at Ballard’s New York Fashion Academy. Back then, the trend was for the well-to-do to leave town when the need struck to blow serious coin on clothing.

“It was about fashion as status symbol,” says Whaley. “People wanted you to know who they were wearing.”

Then came the tech boom of the 1990s, and a commensurate shift in buying patterns. “Labels became less important than finding your own personal style,” he says.

The grunge aesthetic fattened the wallets of Seattle thrift-store owners, and the market for locally made apparel also exploded. “People, mostly the Eastsiders, wanted glam,” says Kelly. “[But] it didn’t last.”

Not many of the boutiques that opened during the mid-decade boom survived after the tech bubble burst, says Whaley. According to Whaley, smaller designers and boutiques are akin to so many indie bands. “They have the people who know who they are, and the folks who patronize them—but outside of those people, nobody has ever heard of them,” he says. That’s why it makes no sense, in Whaley’s opinion, to open a “house of couture,” a term he and most others reserve only for fashion’s well-funded old guard.

Enter De Osu, who claims to have recently secured financial backing, though he won’t divulge how much or from whom he got it. De Osu is making a conscious grab for this town’s couture market, such as it is. To entice Seattle’s deep-pocketed fashion consumers, he’s selling the experience of couture as much as the clothing itself.

“Fashion has gone so far into production, into ready-to-wear, that they miss the human being, which is why they’re creating in the first place,” he says. “We’ve found that in Seattle you have to train people to appreciate the experience of couture.”

Walk into Neodandi on any given day and you’ll most likely be greeted by Karter. A tour will lead to conversation, then a glass of champagne—and if you’re the type who can afford something more exclusive, a personal fitting.

But the full Neodandi experience can only be had at one of the weekly salons. Each Saturday night, there’s an open invitation to all interested parties to attend a small-scale fashion show inside the Western Avenue showroom. Each has a theme, conceptualized by De Osu and his brain trust beforehand. The champagne will flow, and the Neodandi staff, as well as whatever models can be conscripted into service, will take part in a “fashion installation,” in which they’ll try on various pieces from the racks.

A few Saturdays back, the salon included a reading of Hamlet, followed by a themed interactive fashion show dubbed “Who’s Watching Who.” That night, each staff member took turns filming one another while a video feed played against the side wall. “It’s a commentary on the fashion show itself,” said De Osu. “We’re trying to break down the walls and get the people who are going to actually be wearing the clothes involved.”

Located on the north edge of Pioneer Square, De Osu’s showroom is nestled between a furniture store and a vintage sneaker shop. Near the front entrance is a stage. The sewing machine that sometimes rests there is moved to accommodate the models: Karter, and De Osu’s soon-to-be wife, Russian émigré Julia Sandetskaya, rumored to be fronting much of the money for Neodandi’s latest push.

According to Neodandi’s articles of incorporation, Sandetskaya, who has taken the name Ullie De Osu, is the president of the company. She won’t reveal exactly how much she has personally invested in the company, or how much outside financing the two have received since incorporating last August. Like De Osu, however, she does acknowledge that starting a sartorial playground for the rich and fabulous at a time when even those folks are pinching pennies is a chore.

Just before midnight on the night of the show, the crowd is sparse. So the two women take to entertaining each other. From the piping that serves as the central clothing rack, they begin pulling down items and trying them on, giggling like two young girls playing dress-up. Every few minutes, a confused-looking pedestrian passes by the front windows to stop and stare. When Karter changes directly onstage, baring her back to the street, one man lingers a bit longer than usual.

De Osu is in good spirits despite the shortage of attendees, and banters with the regulars who trickle in. He then tries on his menswear and mugs for the cameras along with the rest of the staff, watching as a middle-aged first-time attendee gingerly slides into a revealing mock-hoodie. Before the end of the night, he’ll have another disciple.

Michael Cepress is, along with De Osu, one of only a handful of local designers who own their own storefront. It’s a key step, Cepress says: having a place where your clothes can be seen and not just made. This, he adds, is especially true if your goal is to move beyond commission-based work to the more difficult task of building a brand.

Since opening his eponymous shop on Capitol Hill in 2008, the Wisconsin transplant has tailored the usual in classic menswear—shirts, ties, and trousers—with a chic flair. There’s crispness to his designs, whereas De Osu’s are artfully rugged. During Cepress’ latest open house, he was in full master-of-ceremonies mode, doling out champagne flutes as lithe attendees poked through the racks.

The morning after the occasion, Cepress eases onto his stool, apologizing for the clutter atop his drafting desk. Like De Osu, the 28-year-old is self-taught. But he’s been designing clothing since receiving a bachelor’s degree in art from the University of Wisconsin at Green Bay. He later received a Master of Fine Arts degree from the University of Washington, then began a crash course in costume design at Seattle Opera, eventually graduating to a career in fine tailoring.

“To be a clothing designer,” he says, “it’s important to put forth a professional image, always. When people commission you for a project, they’re saying that they have great confidence in you, and you want them to know that they can count on you.”

If Seattle’s fashion designers have a failing, it’s that some don’t keep that particular commandment, says Cepress. Case in point: De Osu, whom Cepress nevertheless includes on his list of local designers doing “quite solid” work. Logan Nietzel, of Project Runway fame, concurs. Speaking from New York, where he moved two months ago, the former Seattleite says, “You walk into Neodandi and you immediately get a feel for the aesthetic that he’s going for. And that can be rare.”

Along with the plaudits, there are complaints. Reese Henderson, a massage therapist whose offices were once kitty-corner to De Osu’s previous studio inside the OK Hotel, says that De Osu nearly ruined her wedding. She’d seen his designs and was impressed, she says. Desiring an untraditional wedding, she commissioned De Osu to design the outfits she and her fiancé would wear on their trip down the aisle. According to Henderson, the contract went into effect in April 2008, with the agreement that De Osu would be paid $5,000 total, with half paid up front. They agreed that both pieces would be completed by the summer before her February 2009 nuptials.

Ten months after the agreement was signed, she filed suit against De Osu in small-claims court for breach of contract.

Henderson says the June deadline came and went with no discernible progress made on her outfits, while De Osu began demanding more money. By Thanksgiving, says Henderson, he’d ceased returning her phone calls. She won a judgment for $2,250, the total amount she’d paid him in installments.

De Osu won’t address the specifics of the case, confessing only that the experience has made him more careful about taking commissions for wedding dresses. “Brides are really finicky about their desires,” he says. “And that’s understandable. It’s the most important day of their life, and they want the best.”

In De Osu’s estimation, some customers don’t “bring the best” energy to the process of creating. “Some people come with less than adequate [energy],” he says, then complains about having to adhere to a production pace dictated by other people. “And that’s when you realize that brides are really hard to deal with,” he says.

Henderson has since taken to the Internet to ward people off from patronizing Neodandi. The sole review posted on Neodandi’s Yelp.com page, as written by Henderson, reads: “If you hand over your $$ to Nillartey [sic] De Osu or Neodandi Designs, know that you will never see it again nor receive a complete garment in return. Avoid at all costs.”

Tamara Lily and De Osu met in 2004, when the latter walked into the Ballard fabric shop Lily (then named Fidler) was managing at the time. By then, De Osu had already begun designing for local consignment shops, like Synapse 206, whose owner, Tina Bueche, had seen some of his work and encouraged him to continue designing, later buying some of his wares on consignment.

Bueche, who used to own Dutch Ned’s Saloon in Pioneer Square and has long been a fixture in the neighborhood, still has a few Neodandi pieces in her First Avenue shop, though her professional relationship with De Osu has soured. Bueche says she loaned the designer money to sustain Neodandi—money he still owes her. Unfortunately for Bueche, she and De Osu never entered into a formal agreement. And neither did De Osu and Lily.

Coming off a divorce, nearing middle age, and suffering from an unhealthy case of naivete, Lily made Neodandi her life, and tied up her fortunes with a man who gave her confidence.

“He knows how to make you feel good about yourself,” she says. “If you haven’t got it, he knows how to give it to you. Whether he’s sincere or not, his talent, his personality, they suck you in.”

What Lily brought to the table was an ability to sew. De Osu was at the time renting studio space at the OK Hotel. He asked her if she wanted to collaborate, and she agreed. According to Lily, the two had an incredible working dynamic. It was like “falling in love with someone so hard that you don’t have to speak to communicate,” says Lily.

De Osu confirms as much, saying, “There were things that I didn’t know could be sewn by a human, and she’d say ‘Let’s try it'”—and soon it would be “a real garment.”

The apex of their relationship came in 2005, at the fashion show at Trinity the P-I raved about. Things started to fall apart from there.

Lily, who was sitting on a divorce settlement, had been fronting money for rent, marketing, fabric, and production. But even with sales from Synapse 206, commissions, and miscellaneous other streams of revenue, Neodandi would sometimes bring in less than $1,000 a month. Thus they were continually late paying rent on the studio; court records indicate that the two were nearly evicted from their space multiple times.

Meanwhile, the jet-set lifestyle she and De Osu were living was being funded by Lily’s credit cards, which financed scouting trips to New York, production runs on the latest line of garments, and their various fashion shows (which both parties now concede are a relative money pit)—all to build the Neodandi brand.

By July 2006, Lily says she could no longer afford the rent on her Capitol Hill apartment. A year later, she’d had enough. She nearly broke down as she told De Osu she was leaving Neodandi. The next day she cleared out a sewing machine, fabric, and anything else she thought was hers.

De Osu remembers things differently. He claims that Lily asked him to give her the business, and then left him in a lurch with no sewing equipment. “We were a start-up company and we needed to build a following before we started seeing the kind of money we needed,” he says. “But the locomotion process of pushing the business forward—she just couldn’t handle it.”

In the aftermath, Lily filed for bankruptcy. Court records show that in March 2009, she owed $203,782 to parties that she could not pay back, including a $65,000 personal loan from Bueche. Much of the other claims on her credit were Neodandi-related expenses.

Four years after Lily’s departure, De Osu looks back on the period with typical conviction. “I am Neodandi,” he says. “It’s my idea. I have an idea of where I want this company to go, so this was very difficult, because here is this person who doesn’t have a really deep-rooted understanding of where I’m coming from.”

For her part, Lily maintains respect for De Osu’s creative talent, if not his business acumen.

“He’s an artist with a mission,” she says. “But he just doesn’t have any concept for how to manage money.”

Atop the black-lacquered stage at the front of the Neodandi showroom, De Osu fields questions from behind a pair of sunglasses. He and the staff are fresh from a trip to New York, and he is refreshed artistically.

The trip wasn’t all leisure, however: He, Ullie De Osu, Phromnopavong, and Karter spent much of their trip scouting locations for retail space in the Big Apple. Neodandi East is in the works. The Seattle location will remain, but with an entirely different staff.

Ullie takes a moment to explain that New York is the logical next step for Neodandi. “It’s a very good business decision to start here [Seattle], to bring the business to life,” she says in her cheery Russian accent. “But we’re looking at the world market now.”

De Osu takes a sip from the glass of water brought by his doting fiancée, and for a moment there is a flash of the young man he used to be: the socially awkward kid who retreated into books when he found the adjustment to American culture too difficult, butted heads with his Ghanaian father “as if he was my enemy,” and began to envision himself as the King of Pop.

There is some confusion about the specifics of De Osu’s biography. Lily says he told her that he was of Ghanaian descent but born in England. Tatman, the SAM retail buyer so charmed by his designs, says it was her understanding that he is from South Africa.

What people know about him is that his name is Niilartey De Osu and he claims to be from Ghana. Previously, his name was Richard Wilfred Lartey Boye. But that was a different life, and perhaps, as Reese Henderson suggests, a different persona.

His current name is a construction. “Nii” is, by Ghanaian tradition, the name bestowed on the first-born child in a family. “Osu,” he says, is the name of the section of Accra, Ghana’s capitol city, from which his mother hails. “Niilartey De Osu,” he says, is the name of the person he is, rather than the name given to him by people who had their own ideas of who they wanted him to be.

Reached by phone at his home in New Jersey, a man who identifies himself as Sam Boye Sr., De Osu’s father, confirms that the family is of Ghanaian descent, but not much else. “We haven’t spoken to him in a very long time,” he says. “Last I heard he was in Seattle, but I don’t know much more.” He then hangs up the phone.

In De Osu’s account, he was born in Accra, the eldest of five siblings. For as long as he can remember, his plan was someday to move to the U.S, he says. And this is where things get murky. De Osu says that between the ages of 17 or 18—or as he estimates, 1991—he moved to Raleigh, joining his biochemist father. Four years later, he and two friends filled a rented truck with clothing and paintings and drove to Seattle.

Court records and press clippings tell a slightly different story. Documents obtained by SW indicate that De Osu was issued a Social Security number in 1982. An April 1991 issue of the now-defunct Raleigh Spectator includes a review of De Osu’s first public art show. In it, his place of birth is stated as England, and his age as 25. Yet a recent write-up of Neodandi in Seattle Magazine dates his arrival in Seattle as 1985. Asked to account for the discrepancies, De Osu says his memory can at times be hazy, especially when it comes to dates.

What he can remember with some clarity is how difficult it was to adjust to American culture, and to a place where his blackness was “suddenly less.” Before long, he and his father began to clash. De Osu says his dad wanted him to enter a science-related field, or at least a more reliable occupation than professional artist.

In North Carolina, De Osu found friends in books—specifically, art books. He studied them, learned from them, and broke down their work layer by layer. This is why, he claims that despite being self-taught, he learned from the grand masters.

He then discovered Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead, and latched onto the story of protagonist Howard Roark’s struggle against traditionalism as if it were gospel truth. “I followed his path to a T,” says De Osu.

Years before he became an unwilling Tar Heel, De Osu was hanging out with friends in Ghana when Michael Jackson’s “I Want to Rock With You” came pouring through a nearby speaker.

“I believe there are souls that come from the same tree that can recognize each other,” says De Osu. “There was something in his voice that said this was home.”

Years later, after a succession of his Sanderson High School classmates told him he looked just like Michael Jackson, he felt the click again. He started to project an image of Jackson, just as an artist would project an image onto a canvas. He began to dress and walk like the King of Pop. Girls started paying attention to him. Classmates began inviting him to their respective houses. In his mind, De Osu had “transcended black”—just like Michael Jackson.

“And then I decided, ‘OK, I’m ready to paint,'” he says. Thus was Niilartey born.

Inside his back production room, De Osu is surrounded by models, who are getting the rundown of the evening’s events from Ullie De Osu, the coordinator of tonight’s salon. Her future husband stands with his back to his desk, beneath a wall plastered with pictures, including a trio of his heroes: Jackson, Obama, and Tupac. For the occasion, De Osu is wearing a silver sequined jacket similar to the one Jackson made famous. He looks like a disco ball.

The curtain closes, and from behind it Karter can be heard directing traffic. She manages Neodandi, and if fashion design is a form of art, then she is De Osu’s canvas—nearly every garment hanging in the Neodandi showroom was fitted on her.

A year ago, just a few days back from a brief and “unfulfilling” stay in Portland, Karter was walking around downtown Seattle, fresh from an interview at a clothing store she’s now too embarrassed to name, when De Osu abruptly stopped her on the street. He asked if she wanted to take part in a fashion show he was holding later in the week. She went home and logged on to his online gallery, fell in love with his work, and later got in touch to tell De Osu that she’d do whatever Neodandi needed. She’s worked for him ever since.

Tonight’s salon is a “fashion opera” in tribute to Michael Jackson. Karter, like the rest of the Neodandi staff in attendance, is one flute of champagne ahead of the rest of the crowd. Onstage, a Jackson impersonator is pantomiming dance moves to a mixtape of the singer’s greatest hits. About 40 or 50 attendees, who paid a $50 entry fee, mill about and try not to look square. They’re here in part to raise money for Seattle Children’s Hospital: Tonight’s show is also a charity event.

For the past few Saturdays, Neodandi has played host to less-grandiose affairs. But tonight they have sponsors, such as Seattle Metropolitan, and free booze. The show starts, and De Osu stands near the back, watching as the models walk by. On the wall overhead is stenciled the store motto: “In our wake, birds fly.” He is soon greeted by a familiar guy with a mop of gray hair and pants tighter than a 16-year-old emo kid’s. They banter about this motto, which De Osu and his staff have worked long hours trying to put together in time for tonight’s show.

Later, a woman who confesses to have spent a small fortune at Neodandi stands near the stage, as Karter and a succession of impeccably coiffed hipsters re-enact classic Jackson dance moves.

“No one is fucking doing anything like this,” she observes.

No one except Niilartey De Osu—whoever he might be.