One winter day two years ago, the phone rang in a West Seattle townhouse appointed with a thick carpet and wall hangings featuring Arabic script. It was 23-year-old Abdifatah Yusuf Isse phoning home with some surprising news. His family thought he was visiting his girlfriend in Minneapolis during an extended break from studying economics at Eastern Washington University. In fact, he revealed, he was calling from Somalia.

Isse didn’t know exactly where he was, he told his mother, Amina Ali. It was some campsite in the woods, where he was being kept up all night by the sound of hyenas and his fear of snakes.

He said he wanted to leave, but was stuck. The people who had lured him there with a free ticket and a chance to visit a homeland he hadn’t seen since he was 8 had confiscated his passport.

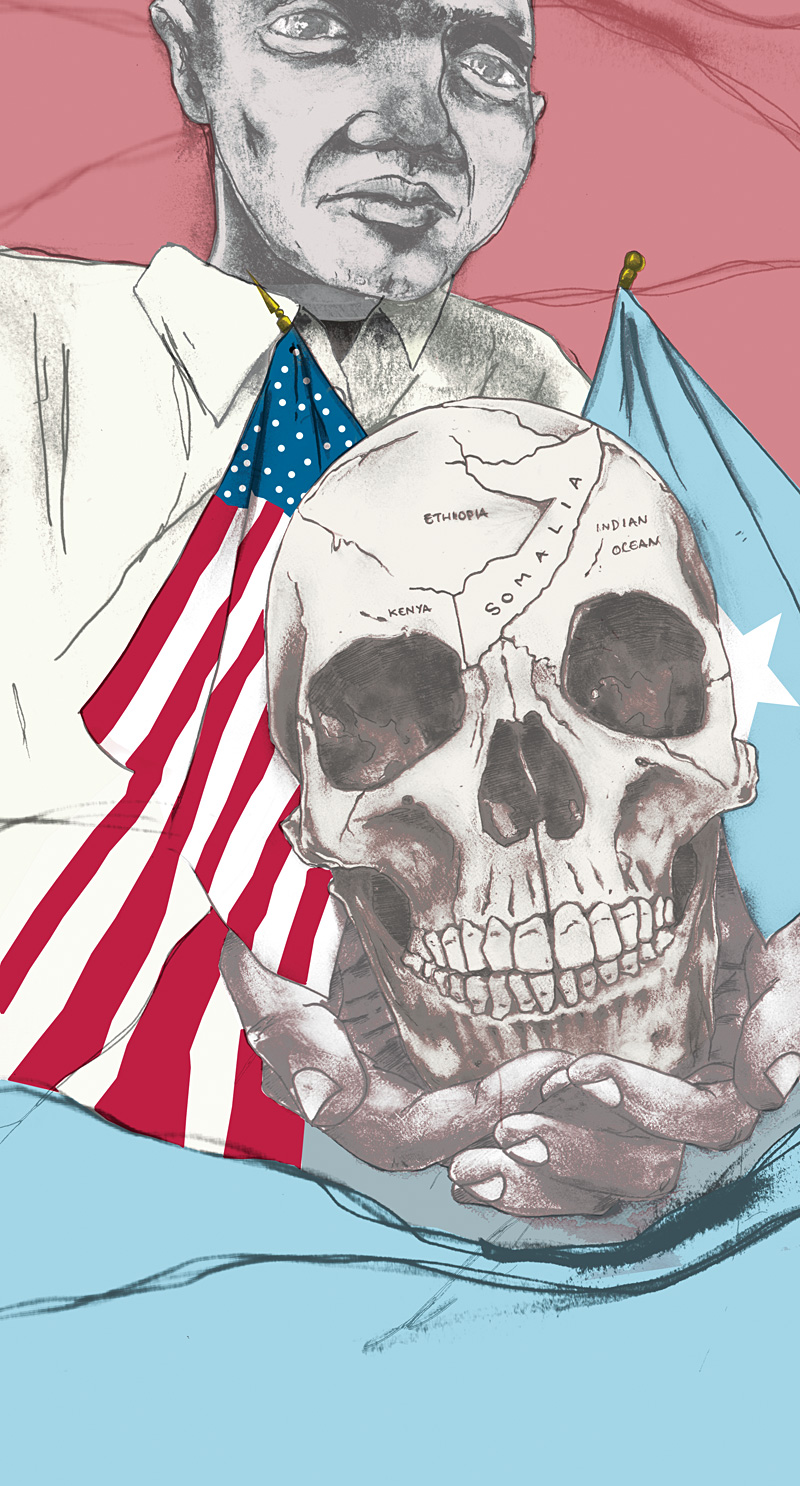

Ali considers her son, essentially, to have been kidnapped. The federal government, however, views him as having participated in terrorism.

The people who flew him to Somalia were operatives of al-Shabaab, an extremist Islamic group backed by Al Qaeda that has kept the country in a prolonged state of violent chaos. Isse stayed at an al-Shabaab safe house when he got to Somalia, was issued an AK-47 assault rifle, and helped build a training camp for a week or two before sneaking out and finding relatives in nearby towns.

He returned to the United States the following spring. Five months later, Shirwa Ahmed, a Somali American who had traveled with Isse to the al-Shabaab camp, drove an explosive-laden Toyota truck into a government office in northern Somalia as part of a coordinated string of suicide bombings that day that killed 20 people. U.S. authorities began investigating Ahmed’s peers, and this past February they arrested Isse at Sea-Tac Airport as he was about to board a flight back to Somalia. He said he was going to work for an uncle there.

Isse has since pled guilty to a charge of providing material support to terrorists, and is in jail in Minneapolis awaiting sentencing. His attorney declines to discuss details of the case, saying he is forbidden to by court orders sealing much of the relevant information due to an ongoing federal investigation.

Isse is cooperating with that investigation, which has discovered approximately 20 young Somali Americans who in the past three years have traveled back to their country of birth to become entangled with al-Shabaab. At a press conference in Minneapolis last month announcing the indictment of eight of these men, federal authorities stressed the danger of this first wave of homegrown terrorists. (Last week came news of a second wave, with the arrest of five young Americans in Pakistan suspected of plotting terrorism in Afghanistan.)

“The national-security implications are evident—Americans with U.S. passports attending foreign terror camps,” said Ralph Boelter, special agent in charge of the FBI’s Minneapolis field office, according to an Associated Press report.

In the FBI’s field office in downtown Seattle, David Gomez, assistant special agent in charge, elaborates: “The question is whether there’s a potential for someone to go over there and then come back and commit a terrorist crime back here”—or, he adds, in Europe, where American passports usually guarantee easy access. He calls the investigation of Somali terrorists “among the highest priorities in anti-terrorism” since 9/11.

For his office, he says, “our major investigative concern is to determine whether or not a recruitment network exists in Seattle.”

The most recent indication of such a network came with the Sept. 17 suicide bombing of an African Union peacekeeping base in Mogadishu, Somalia’s capital, which killed 21 people. A Somali-language Web site called Dayniile.com identified one of the terrorists as a Seattle man, according to CNN. Local Somalis tell the Weekly they have spoken to the man’s father since then. A resident of the Rainier Valley, he tearfully acknowledged his 18-year-old son’s death, these sources say, although the FBI is still working on confirming the suicide bomber’s identification. (The Weekly could not reach the father directly for comment.)

Seattle has one of the three largest Somali communities in the country, along with Minneapolis and Columbus, Ohio. While the U.S. Census does not track Somalis specifically, a report using data from 2006 through 2008 documents approximately 22,000 East Africans in the Seattle metropolitan area. Local Somalis believe the current number is as high as 40,000.

They have grappled with the news of terrorists from their community in different ways, with some trying to downplay the threat and others sounding the alarm. Many feel as if they’re under increased scrutiny in their new home. “We are a community under investigation, basically, for a few bad apples,” Halima Dahir told some 100 Somalis gathered at the Rainier Vista Boys and Girls Club on Oct. 20. The forum was organized by a coalition of Somali groups that came together in the wake of revelations about a local terrorist connection.

About six months ago, for example, law-enforcement authorities caused a stir when they showed up at a parking lot outside a South Seattle apartment building populated by Somalis. The officers were showing pictures of Somali men and asking residents if they knew them, according to Arsalan Bukhari, executive director of the state branch of the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR). Bukhari, who received a call from a disturbed resident, says he doesn’t know what agency the officers were from or who the men were in the pictures.

But Bukhari aims to make sure people in his community know that they don’t have to talk. In fact, he highly recommends they don’t.

That’s one message he delivered in a presentation at the Abu-Bakr Islamic Center after prayers one recent Friday night. The mosque is housed in a squat former casino on Tukwila International Boulevard, next to a Pawn X-Change. Bukhari was invited to give a presentation there by the recently formed Somali coalition.

He addressed various kinds of discrimination Muslims may face, as well as how to handle questioning by law enforcement.

“We at least want people to know their basic rights,” said Dahir, a coalition leader who organized the event. A willowy Harborview Medical Center nurse attired in a black headscarf and dress, Dahir moved around an enclosed chamber of the mosque reserved for women, handing out CAIR pamphlets and trying to drum up attention. It was a challenge because the 30 or so women sitting on a plush, patterned carpet—the only furnishing in the big, white-walled room—couldn’t see Bukhari through the darkened windows that look out onto the men’s chambers. They read prayer books or listened listlessly.

But a few visibly perked up when Bukhari got to the point about what to do if police or the FBI came knocking. “You never have to let law enforcement into your home unless they have a warrant,” Bukhari says. “Otherwise, you can simply say ‘I don’t want to talk to you, please leave.’

“There’s nothing to gain from talking to law enforcement,” he continues. “There are too many things happening to Muslims recently.

“I can’t emphasize enough,” he repeats, “you have the right to remain silent, so please practice it.”

The motivations of Isse, and others like him, remain obscure. Ayan Musse, another organizer of the new Somali coalition, notes that most of the men who returned to Somalia were in their 20s—too young to remember much about the country they left after it dissolved into civil war in the early ’90s. She concludes that the flight of these young men says more about their life here than their loyalty to any particular Somali cause. “You have to be out of hope in order to go to a country you can barely remember,” she says.

The poverty rate for East African families in metropolitan Seattle is 32 percent—four times the rate for families as a whole.

While many Somalis work as taxi drivers or day-care and home health-care workers, they often rely on subsidized housing. It’s hard to walk through Rainier Vista and NewHolly—Seattle Housing Authority complexes in the Rainier Valley—without seeing Somalis, the women particularly recognizable by their flowing headscarves and ankle-length skirts, or by the more conservative billowing cloaks known as jalabib. There’s even a little Somali grocery store fronting Rainier Vista—one of numerous such stores and cafes that dot Rainier Avenue South, Martin Luther King Way, and Tukwila International Boulevard, where imports like moong beans, powdered ginger, dried figs, and huge bags of basmati rice sit side by side with American staples such as Corn Flakes, Cream of Wheat, Pampers, and baby formula.

Those who work with Somali kids say they face steep challenges to succeed in school. Ubax Gardheere, who runs an after-school tutoring program funded by a Massachusetts nonprofit and located at the Matt Griffin YMCA in SeaTac, says that some of the children she encounters occupy a linguistic no-man’s land. Often growing up in refugee camps outside their homeland, they are less than fluent in Somali; new to this country, their English isn’t great either. Naturally, they don’t just have trouble speaking, but reading and writing as well.

At a tutoring session one day, between handing out test-prep worksheets and after-school snacks, the 29-year-old Gardheere explains that parents, often poorly educated and coping with large families, may not be able to help with homework. She points to a 12-year-old working industriously at one table, whom she notes is the oldest of six born to a mother not yet 30.

News accounts of the 20 men lured back to Somalia reveal that some were indeed struggling here. They include a community-college dropout and a one-time gang member.

Yet immigrants of all nationalities struggle, and few turn to terrorism, or even retreat to the land they left. For all their hardships, most say they are better off here, and Somalis are no exception. Collecting her third-grader one day at Gardheere’s tutoring program, Fatumo Ali tells of the day a gang of gun-wielding teens walked into her Mogadishu house. “They say ‘Go, go, go, or else we’re going to kill you,'” the 42-year-old, draped in a black headscarf and dress, recounts.

Ali grabbed her three kids and ran, joining a flood of refugees attempting to leave the country, some by way of the Indian Ocean along which Mogadishu lies. She found a small boat going to neighboring Kenya, but there wasn’t enough room for her entire family. She sent her kids off with relatives.

On the journey to Kenya, the boat capsized. Her six-year-old daughter died.

She and her surviving family members nevertheless made their way to the U.S. “We came here, we get work, we get peace, we get a house, we get everything,” she says. She runs a small day care in her SeaTac home. Her husband drives a taxi. They live in a house given to them by Habitat for Humanity.

Her view of the United States: “I love it. I love it. I love it.”

Abdifatah Isse also met the difficulties of life in a new country with aplomb. At Roosevelt High School, he was taking regular courses, not those for English Language Learners. He struck his school counselor, Wendy Krakauer, as “very sharp, very verbal. He just had a spark about him.”

He was also ambitious. Although he had not done well enough in school to meet his goal of attending the University of Washington Business School, he settled on Eastern Washington University as the next-best choice. “We talked about what it would be like to be an African student east of the mountains,” Krakauer says, adding that he was up for the challenge of being a minority there. Enrolling in 2003, he called himself “Abdi” and talked with his advisor, economics professor Grant Forsyth, about his desire to use his bilingual skills by working with an international organization like the World Bank or the International Monetary Fund. Forsyth says he encouraged Isse to enroll in a graduate program that focused on international development.

Isse struggled with some of his courses, Forsyth recalls, but he found that typical of a lot of students who come out of public schools without the math skills they need for studying economics.

In other ways, too, Isse struck Forsyth as an average American kid. “He had a very slight accent—that was about it.” He was “fastidious” with his appearance and wore “baggy but stylish” jeans, Forsyth adds. “Always very polite,” he moved easily among immigrants and non-immigrants alike.

And though Islam frowns on alcohol and drugs, Isse seemed to have typically college-age attitudes toward those as well. In 2003, according to municipal court records in Cheney, Wash., he was charged with being a minor in possession of drugs and alcohol. In 2005, he was also charged with issuing bad checks.

Forsyth does not remember precisely the last time he saw Isse, but says he was close to having enough credits to graduate. University records indicate he left in 2007 without a degree. His 22-year-old brother Hussein says Isse was taking a break before taking the class or two he needed to complete his requirements.

Hussein and his mother talk about Isse on the doorstep of their West Seattle home, with Hussein translating for his mother, who wears a vivid blue headscarf. Hussein, sporting braids, a baseball cap, and a key chain with a Pepsi logo around his neck, also went to Eastern Washington University, but says he dropped out for financial reasons. He is currently studying criminal justice at ITT Technical Institute.

He asserts that his brother was not excessively religious, although Isse did observe the Islamic call to prayer five times a day. However, Hussein says his brother “wanted to learn more,” and the men who recruited him in a Minneapolis mosque offered “to teach him a lot of things he didn’t know.”

Hussein and his mother profess a hazy knowledge of who these men were and what exactly they told Isse. Hussein says the men asked his brother questions about his education and study of economics, giving him the impression that he would be used in some “political” capacity. The main thing he knew, according to Hussein, is that the men offered a free ticket to Somalia and financial support once there.

As a child, Isse had lived a comfortable life in Mogadishu. His now-deceased father owned several gas stations and earned enough to support two wives (as was legal in Somalia) and their children, according to Hussein. But Isse’s memories of that time were fleeting: visiting a movie theater, going to an aunt’s grocery store, playing under couches. With an ailing grandmother and other relatives there whom he had last seen 16 years prior, he seized the opportunity to go back, his family says.

“He just wanted to experience it—to smell it, to feel it,” Hussein says, adding that his brother particularly looked forward to visiting the country’s beautiful Indian Ocean beaches.

In other words, it may have been precisely because he could barely remember his homeland that he was drawn back to it.

Was that all? Judging by court documents, it’s plausible that Isse may not have understood everything his recruiters represented when he boarded a Dec. 8, 2007, Northwest Airlines flight to the Netherlands, with a final destination of Somalia. The U.S. government had not yet designated al-Shabaab a terrorist organization; that didn’t happen until March 2008, when Isse had already left the al-Shabaab camp. The feds nevertheless accuse him of maintaining contact with people who had “knowledge” of al-Shabaab recruitment upon his return to the U.S.

Still, court documents in his and related cases suggest that, at least for some, a return to Somalia was driven by more than a yearning to see a land of distant memory. Isse left the U.S. as “part of an agreement” with several others to “travel to Somalia and fight against Ethiopian soldiers whom they believed to be occupying the country,” the government alleges.

Indictments of others unsealed last month describe a meeting in Minneapolis between a former taxi driver named Cabdulaahi Ahmed Faarax and potential recruits. (It’s unclear if Isse was among them.) Faarax, who had fought in Somalia and returned to Minneapolis, told of experiencing “true brotherhood” while fighting, promising that “jihad will be fun.” He let recruits talk by phone with current fighters in Somalia.

Despite the religious implications of the mention of jihad, Somalis and federal authorities speculate that nationalism, rather than Islamic extremism, is the dominant force leading Somali Americans to join al-Shabaab.

In 2006, Ethiopian forces, with the aid of the U.S., came into Somalia to battle an Islamic coalition that had seized power. The Islamic Courts, as the coalition was known, was hailed by many Somalis inside and outside the country for finally imposing order, albeit along the lines of the strict Islamic laws called Shariah. But the U.S. suspected the coalition of having ties to Al Qaeda. Ethiopia, a largely Christian country, also viewed the neighboring Muslim regime as a threat. The Ethiopians ousted the Islamic Courts and left their troops in Somalia for several more years to prop up a struggling, Western-backed government.

The occupation reignited historic tensions between Ethiopians and Somalis. “Al-Shabaab was just a vehicle to fight the Ethiopians,” says the FBI’s Gomez.

Abdulkadir Aden, a former president of the Somali Development Bank who now runs a MaidPro franchise out of Tukwila, says al-Shabaab Web sites broadcast this message: “Let us liberate our country.”

It’s a message that still has currency, even though Ethiopia has officially left Somalia. (Ethiopian soldiers continue to make periodic sorties across the border, according to Gomez and Somalis who follow events back home.) And it’s one that resonates with some local Somalis, regardless of their feelings about al-Shabaab. Nordin Wassame is the proprietor of Banadir Super Store, a Rainier Avenue establishment selling Islamic fashions he designs himself and has made in China and Thailand. In his store one day, the soft-spoken 43-year-old shows a flash of anger when asked about the Ethiopians.

“The Ethiopians try to oppress our people,” he says. “They come in [to Somalia], they kill the people. They take people’s money, their cars. They kidnap people’s sons and daughters.”

It’s nothing less than “genocide,” he continues. “They’re saying they want to fight the Muslims and eliminate them.” He lauds the Somalis who “stood up and fought back.”

Nevertheless, he says doesn’t support al-Shabaab, which attacks not only Ethiopians but the government it hopes to depose.

He does, however, follow the Web site of another rebel group, the Ogaden National Liberation Front, which represents ethnic Somalis living in eastern Ethiopia who are fighting for their region’s independence.

The name of the group has come up before in Seattle. In 2006, federal agents deported Abrahim Sheik Mohamed, then the leader of Rainier Valley’s Abu-Bakr Mosque. Although immigrant groups questioned the evidence, the feds claimed that the imam was a covert fundraiser for the ONLF.

They also said Mohamed acted as a spiritual advisor to a group of young men who congregated at Crescent Cuts, a Rainier Avenue barbershop run by a charismatic ex-con named Ruben Shumpert. In late 2004, the African American barber, a convert to Islam, was charged with illegal possession of a weapon and passing counterfeit money. But the feds implied that he had the makings of a terrorist.

At his shop, where he welcomed troubled young men to hang out and even sleep if they needed a place to, “jihad” was a subject of frequent conversation, according to court documents. Shumpert would play motivational videos like 19 Martyrs, a tribute to the 9/11 terrorists.

Shumpert protested in a lengthy statement to the court that he was merely allowing the subject of jihad to be openly discussed. “If we don’t address ‘jihad,’ which means striving and not Holy War, we are leaving our people to be taught by the very extremist [sic] we oppose,” he wrote.

Yet when he skipped the country in advance of his November 2006 sentencing, saying he felt persecuted because of his religion, Shumpert sought refuge in Somalia and apparently joined extremists there. In a call from Somalia to an FBI agent here, he promised to “destroy everything the United States stood for.” Internet reports, yet to be confirmed by the FBI, say al-Shabaab announced that Shumpert was “martyred” last year while fighting the Ethiopians.

The ramshackle two-story building that used to house Shumpert’s Crescent Cuts now contains Shangani Bandiri Groceries and Deli. It has a couple of tables in the back where diners can eat Indian-influenced Somali fare such as kati-kati, a spicy scramble of meat and strips of chapati, or Indian flatbread.

Behind the counter on a recent day, sunglasses perched atop a tousle of curly hair and a cell phone held to his ear, stands Osman Omar Muhidin. When he gets off the phone, the 24-year-old explains in nearly accentless English that he’s from Somalia but has no desire to go back. His memories of the place include the death of his father, shot by machine gun–wielding gangsters in retribution for his father’s slaying of a man who tried to rob his house amid the chaos of the civil war.

In contrast to the gang of followers who used to gather here, the only people present this afternoon are the occasional customer and a chatty, 21-year-old Somali store assistant named Samira Ibrahim. She says she did return to Somalia three years ago—not to join al-Shabaab but to visit relatives and postpone an arranged marriage her parents had planned. She was stuck there seven months, after the Ethiopians invaded and the airports closed.

She describes a variety of harrowing experiences there: seeing police under the then-Islamic regime beat a man and a woman walking together on the street, in seeming violation of strict Muslim morals—although they were actually mother and son, she learned through talking to them; a hasty marriage to a local that ended badly; and an arduous drive, while pregnant and suffering from malaria, to ironically, Ethiopia, where she enlisted the help of the American embassy to come home.

“I went through a rough, rough time, when I should be kickin’ it with my friends,” she says. When her parents recently offered to take her to Kenya to see relatives, she declined, saying she never wanted to go to that part of the world again.

While it might seem that Shangani Bandiri Groceries and Deli is not now a breeding ground for terrorist repatriates, FBI and police officers have made a point of stopping by. “This place has some history,” Muhidin says he was told by a police officer, who suggested that the proprietor prove to law-enforcement officers that it had changed. So about six months ago, he invited the officer and a colleague to lunch.

Muhidin appears not to mind the law-enforcement attention. He says he wants to get some kind of program for Somali youth off the ground, and plans to ask the FBI agent who came around for help.

Local Somali blogger Abdirahman Warsame also doesn’t object to law enforcement’s investigation of his community. In fact, he’d like more of it. “I happen to believe there is a cell here,” he says, although he cannot point to proof beyond the several known cases.

His blog, Terror Free Somalia Foundation, regularly broadcasts the latest horrors of Somali terrorism to an English-speaking audience. Assembling stories and pictures from other media, he chooses the most graphic descriptions and images he can find. His blog’s coverage of a Dec. 3 suicide bomb at a university graduation in Mogadishu showed the limp body of a government minister drenched in blood. A September story on al-Shabaab’s enforcement of Islamic law features pictures of amputated hands and feet—belonging to thieves—hanging on telephone poles.

He says he’s trying to alert the West to brutalities in Somalia that are not fully appreciated. And he forecasts that this is just the beginning. “There is going to be another Taliban just like there used to be in Afghanistan—not only in Somalia but in the Horn of Africa,” says Warsame, a clean-shaven 38-year-old who works at Fisher Plaza.

When Dayniile.com implicated a Seattle man in the Sept. 17 bombing, Warsame tracked down his father at a Somali store and coffee shop on Rainier Avenue. “I’m sorry about the loss,” he says he told the 50ish man with a lame leg. The father confessed his grief and the FBI’s recent visit to his house to take a DNA sample, to be compared with that of the suicide bomber. Warsame says he gave the father his card and told him to get in touch when he was ready to talk.

The blogger says he wants the father to explain how this could have happened. “I’m trying to figure out the face of evil,” he says.

It’s personal for Warsame. He says his parents ran a string of grocery stores in Mogadishu until the war. Like so many, he had to flee suddenly as thugs confiscated his family’s house and stores. He escaped to Kenya by foot.

He seems settled now. He lives in a Bellevue apartment complex, near its pool, with his wife, a Macy’s sales associate, and his children, a 9-year-old girl and a 6-year-old boy. On a recent visit, he pulls out a picture of his kids dressed up for Halloween as a Somali pirate and an American Marine—inspired by last spring’s standoff near the Somali coast, an incident apparently independent of al-Shabaab terrorism. Laughingly, he makes his allegiance clear: He’s a proud American.

But now he feels that the same forces that once purged him from his home—under the guise of al-Shabaab—are haunting him in his place of refuge. “They’re following me,” he says. “They’re taking our kids.”