Yeah, yeah, the Internet is killing the printed page—it was in all the papers. But four-color inks may yet rescue publishing from the gray dawn of Kindle-dom.

Exhibit A: Darwyn Cooke’s The Hunter (IDW, 144 pp., $24.99), adapted from the novel by Donald Westlake (a/k/a Richard Stark). Handsome antihero Parker—betrayed by a fellow thief—is more cauterized than hard-boiled, threatening hookers and blasting holes in crime bosses with the aplomb of Mad Men’s Don Draper lighting a cigarette. Cooke brilliantly captures New York’s early-’60s skyline, fashions, and cars, integrating cool gradations against black brushwork as smoothly as a jazz soundtrack.

Delving deeper into the underworld, Dino Buzzati’s astonishing 1969 Poem Strip casts a rock star in Milan as Orpheus (NYRB, translated into English for the first time by Marina Harss, 224 pp., $14.95). To soothe the dead, “Orfi” sings of “when the autumnal sorcerers trail their long dark shadows through the gardens of joy” while searching for his girl across a limbo resembling one of de Chirico’s metaphysical plazas. Buzzati (1906–72) melded his swinging drawings of witches and urbane Milanese to a prose poem that embraces civilization’s divine contradictions, a world in which “the nun on a pilgrimage glimpses a black sabbath in the forest.”

A lucid nightmare, Al Columbia’s dazzlingly well-drawn Pim & Francie (Fantagraphics, 240 pp., $28.99) features vignettes of its young protagonists menaced by creepy relatives or starring in exceedingly grim fairy tales. These inky visions seem unearthed from the deepest vaults of Uncle Walt’s id.

If Harry Potter is your cup of tea, avoid writer Mike Carey and artist Peter Gross’s The Unwritten (Vertigo, ongoing monthly, $2.99). The plot centers on Tom Taylor, the inspiration for his father’s insanely popular Tommy Taylor books about a boy wizard who battles world-destroying vampires. Dad disappeared long ago, bequeathing Tom nothing more than a weary regimen of book signings, which ends when a shadowy cabal manipulating world literature frames him for mass murder, sending this meta-lit romp into mordantly witty overdrive.

Ken Dahl confronts his herpes affliction through comically grotesque drawings and tongue-tied dialogue with prospective dates in Monsters (Secret Acres, 208 pp., $18). The virus itself grows into a large blob that mutters, “I’m just another lifeform trying to survive in this weird, fucked-up world.” Caldecott Medal–winning artist David Small shares this sentiment in Stitches (W.W. Norton, 336 pp., $24.95), which movingly recounts his bleak 1950s childhood with a closeted lesbian mom and pipe-smoking radiologist dad. Small’s often-wordless ink-wash panels shift between the smokestack pall of Detroit and brightly lit hospital corridors with graceful fluidity.

Upping the word count, Boom Studios’ Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (24 monthly issues, $3.99 each) includes the entire text of Philip K. Dick’s classic 1968 sci-fi novel. Does appending “he said gloomily” to an obviously glum character’s dialogue balloon negate the premise of graphic novels—that visuals can replace text? Maybe. But Tony Parker’s volumetric art fleshes out Dick’s wide swings between pulp verbiage and pithy insights (his electronic “Mood Organ” presages our current cornucopia of mood-altering pharmaceuticals). If you’re a fan of Blade Runner but have never read the source material, this experimental adaptation should be just the ticket.

Bertrand Russell’s struggle to reconcile philosophy and pacifism through the purity of numbers proves a surprisingly lively tale as told by writers Apostolos Doxiadis and Christos H. Papadimitriou in Logicomix (Bloomsbury, 352 pp., $22.95). Artist Alecos Papadatos uses changing fashions and technological updates to propel the English mathematician’s bio from rigid Victorian upbringing through tortured personal relationships to his enduring humanistic legacy.

Anything but Victorian, Nell Brinkley (1886–1944) celebrated the Roaring ’20s with sinuous lines and colors as lurid as William Randolph Hearst’s presses could muster. Author Trina Robbins notes, in the lavishly oversize The Brinkley Girls (Fantagraphics, 136 pp., $29.99), that the illustrator “closely resembled the girls she drew.” But Brinkley, with her thrilling fantasias of pirate abductions and aviatrix romances, remains an inspiration beyond flapper flamboyance to any young lady seeking to break into the boys’ club of high-end illustration.

The 15 cliffhangers on huge broadsheet pages in each of DC’s weekly Wednesday Comics (12 issues, 16 pp., $3.99) featured franchise players Batman and Superman, of course. But it was Paul Pope’s trippy take on Adam Strange, replete with blue apes against op art backgrounds, and Kyle Baker’s slashing and comically arrogant Hawkman that proved it’s often secondary heroes who are ripest for artistic extravagance.

Political cartoonist Herbert Block’s career spanned 13 presidencies bookended by two lemons—Hoover in 1929 and W. in 2001. Herblock (W.W. Norton, 304 pp. plus DVD, $35) features more than 18,000 cartoons that skewer demagogues (Joe McCarthy with his tar brush), hypocrites (Nixon hides behind an American flag labeled “National Security Blanket”), and ineffectual leaders (Jimmy Carter pounds the Oval Office desk, demanding, “Who’s in charge here?”).

Joe Sacco’s Footnotes in Gaza (Metropolitan, 416 pp., $29.95) also traverses contentious history, combining archival research with frayed memories to piece together a half-century-old tale of Israeli soldiers massacring Palestinians. One survivor, an old man now, says, “At that time I didn’t deserve to be shot. But now I deserve it.” Sacco draws him with a grin that captures the brutal merry-go-round of killing and revenge that forever blights the Holy Land.

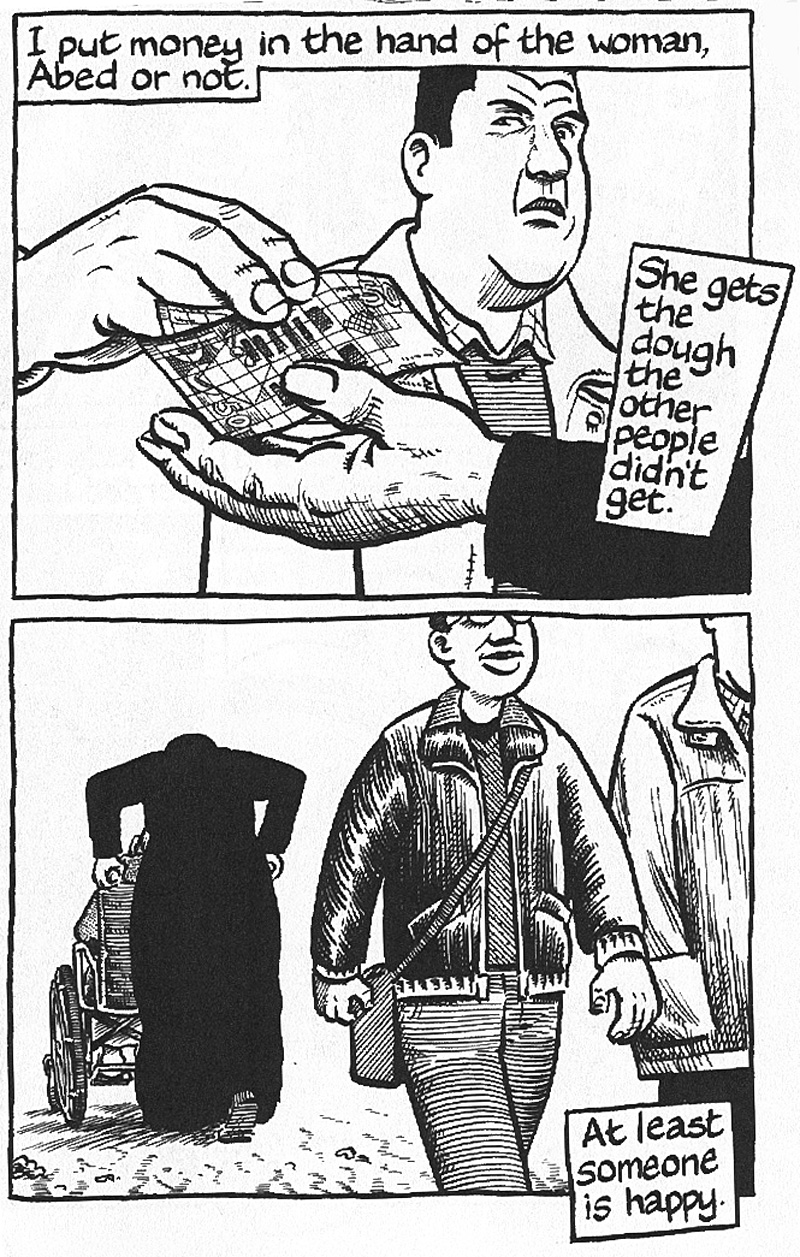

In Studs Terkel’s Working (The New Press, 224 pp., $22.95), various artists and writers adapt parts of the Pulitzer-winning author’s most enduring book, originally published in 1974. Lance Tooks’s layers of Zip-a-tone add jazzy panache to an interview with saxophonist Bud Freeman, and Ryan Inzana’s rough inks lend hardscrabble texture to Harvey Pekar’s take on “Elmer Ruiz, Gravedigger.”

Studs would have appreciated the pathos of Craig Yoe’s scoop in Secret Identity (Abrams, 160 pp., $24.95). Artist Joe Shuster, with writer Jerry Siegel, created Superman in 1938, but the pair earned only piecework rates for their efforts, eventually losing control of their lucrative creation and falling on hard times. A few years ago, Yoe stumbled across some bondage comics from the ’50s, whose brawny men and bent-over buxom babes resembled Superman and Lois Lane. And wasn’t that Jimmy Olsen pushing reefer? Never the subtlest artist, Shuster—whether desperate for cash or indulging an unsuspected dark side—proved incapable of concealing his style in these anonymous porn pamphlets, which the Supreme Court eventually deemed obscene.

Comics. Good work when you can get it.