In August, the city of Spokane Valley wanted to prohibit panhandling near automatic teller machines, to people getting in or out of cars, at intersections and freeway on/off ramps, and after dark. (Somewhere, former Seattle City Attorney Mark Sidran smiled.) Then the Spokane Valley City Attorney’s Office looked into the idea and decided it was unconstitutional, and the proposed ordinance was shelved.

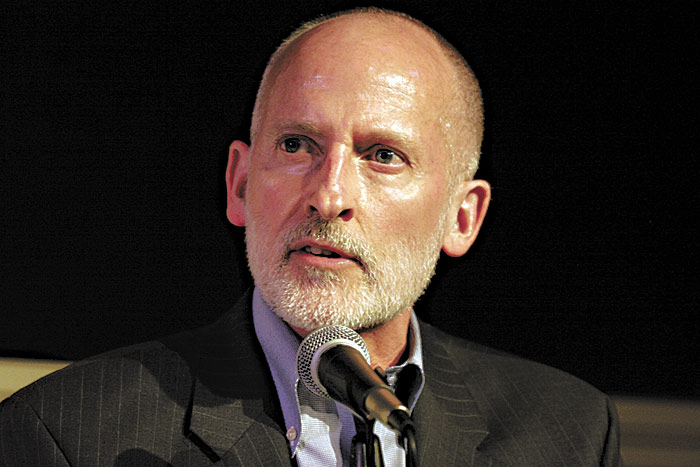

But it lives on—in Spokane, for example, where it’s already on the books, and now in Seattle, where City Councilmember Tim Burgess is looking to get a similar ordinance passed before year’s end. Burgess appeared on KUOW’s “The Conversation” on Sept. 16, arguing that the prohibitions are necessary because of a “pervasive problem we have with street disorder in many of our neighborhoods and downtown.” As evidence, he noted that his office receives one to two calls a week complaining about aggressive panhandling. Allowing it to continue, he argued, will just lead to an escalation of crime, as potential lawbreakers perceive a culture of permissiveness.

A few problems stand in the way of Burgess’ proposal, however. To start, much of the conduct that is the source of Burgess’ complaints is already prohibited—which raises questions about the necessity of a new statute and may make it more subject to constitutional challenges, as laws that restrict free speech must be narrowly written and necessary to accomplish their aims. Seattle’s pedestrian interference law, passed by the City Council in 1993, already makes it illegal for a panhandler to make a reasonable person feel fearful or compelled to give money, or to obstruct pedestrian or vehicle traffic while panhandling.

When asked by KUOW host Ross Reynolds whether the whole approach doesn’t constitute picking on the poor and homeless, Burgess replied that the city already has many programs to help the homeless, insinuated that most homeless don’t panhandle (he cited a conversation he had had with a social worker, none of whose 100-plus clients allegedly panhandles), and added that most of those cited for aggressive panhandling are under supervision for previous criminal offenses.

When the Seattle Displacement Coalition’s John Fox heard those comments, he “had a very visceral reaction. A significant proportion of the homeless do panhandle,” he asserts, citing his own experiences working with homeless youth. “But the bigger issue is the inference that all panhandlers are criminals. Violence against the homeless is very real, and this sort of typecasting makes it easier to ignore them or abuse them.”

Fox sees Burgess’ proposal as part of a larger effort to remove the poor from public view “to appease a certain segment of the merchant community,” he says. “The whole idea is to get an array of laws in place so that, at one point or another, this population is going to run afoul of one of them.”

Another potential problem for Burgess is constitutionally protected free-speech rights. Advising against Spokane Valley’s proposed law, Deputy City Attorney Cary Driskell cited an analysis by the Spokane Center for Justice that “assert[s] that the proposed ordinance is likely an illegal content-based restriction on speech. Because it is content-based, it must be narrowly tailored to a compelling government interest, such as public safety.” Driskell’s memo cites the case Berger v. City of Seattle, which centered on a balloon artist’s right to peddle his wares at Seattle Center. In that case, the 9th Circuit ruled that preventing “captive audiences” from feeling uncomfortable when solicited is not a compelling government interest.

To go ahead with the restrictions, continues Driskell, “There would have to be something like an identifiable public-safety concern, supported by statistical data.” A councilmember’s assertion of one to two phone calls a week about the problem of aggressive panhandling might not cut it.

Driskell contends that ordinance supporters would need to be able to point to statistics showing that when there’s panhandling and a captive audience, there’s a higher incidence of crime. “You’d need some sort of nexus, a direct tie,” he says. “Absent that, I think courts are going to be reluctant to uphold an ordinance that is restricting free-speech rights.”

Moreover, Burgess wants to exempt Real Change vendors from the law. “It would not apply to [the vendors] because they’re not presenting a problem,” he said on KUOW. Similarly, he argued that while panhandlers holding signs at street corners would be subject to the law, political campaigners holding signs would not—a questionable distinction if the aim, as Burgess contends, is to avoid distracting drivers, not to suppress the speech of panhandlers. Told of these comments, constitutional scholar Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the University of California, Irvine School of Law, writes, “My sense is that the exception for vendors of newspapers and those in the street will make this particularly vulnerable [to constitutional challenge].”

For now, the ACLU of Washington is expressing unease. “We have some concerns based on what we heard,” says spokesperson Doug Honig, “but we haven’t seen anything in writing. We look forward to talking with the councilmember and learning more about what he has in mind.”

As for Burgess, the man who said we “can’t afford not to” pass these laws is suddenly mum. In response to a request for an interview with the councilmember, Burgess aide Nate Van Duzer says: “The councilmember wants to hold off on making further comment on this until we have legislation on paper. He started the conversation, and now he’s waiting to hear back from stakeholders.”

He will hear from some of them shortly. When Fox caught wind of Burgess’ proposal, he sent the councilmember a letter expressing his concern that civil-liberties and homeless advocates had not been consulted, requesting a meeting. Burgess agreed to meet with Fox on October 9.

Fox says he plans to bring attorneys and homeless advocates with him, in the hope that they can help convince Burgess to abandon the proposal. “We’re going to lay out all the arguments why he should simply drop this idea, from constitutional questions to divisiveness it will cause,” Fox says. “I don’t think Burgess knows what he’s getting into.”