Since 2005, when Hunter S. Thompson committed suicide, friends and colleagues have steadily exploited his legacy by writing uninspired “My friend, Hunter”–type memoirs. His longtime illustrator Ralph Steadman wrote The Joke’s Over, a weak memoir that, given their legendary friendship and Steadman’s strong writing skills, should have been better. Thompson’s wife Anita set out to shed light on his work ethic and wrote a disposable book called The Gonzo Way. Sheriff Bob Braudis of Pitkin County, Colorado, where Thompson had lived since the ’60s, wrote a relatively unfunny book called The Kitchen Readings. And Rolling Stone founder Jann Wenner, naturally, rushed an oral biography to publication that was, as Thompson would have said, a real hamburger job.

The prospect of any new “this-is-what-Hunter-was-like” narrative gets fans salivating. But the truth is, nobody wrote about or documented Hunter S. Thompson better than Hunter S. Thompson. He was a textbook narcissist, and if you need proof, check out The Proud Highway and Fear and Loathing in America, which reprint nearly every piece of correspondence the man typed from his late teens to his early 30s. How did editor Douglas Brinkley obtain copies of these letters? Easy: Thompson kept carbon copies of each for himself. And that’s not all: He also kept photos and videos of himself, ideas scribbled on napkins, drafts of his books, and faxes to his editors.

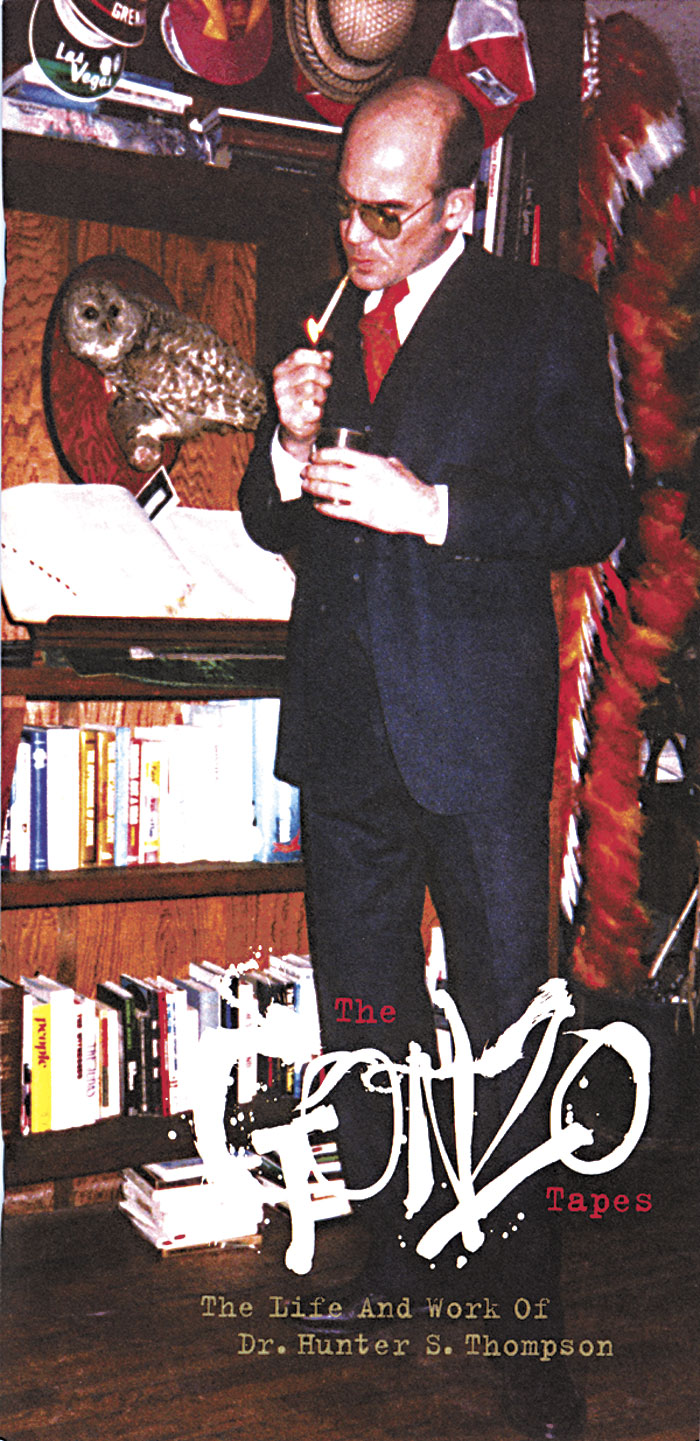

While other writers might keep journals, Thompson kept his on cassette tape (his Norelco recorder serving as both diary and reporter’s notebook). Hence, The Gonzo Tapes, a five-disc collection of those recordings, which were first unearthed and used by Alex Gibney in his excellent documentary Gonzo: The Life and Work of Hunter S. Thompson. Like you’d expect from a collection of someone’s journals and notebooks, much of this box set is sandpaper-dry with bits of juicy insight only the serious Thompson aficionado will appreciate. And by serious aficionado, I mean the type who would sit through two discs of coked-up ramblings from Oscar Zeta-Acosta (Thompson’s attorney, aka “Dr. Gonzo”) just to hear that Brewer & Shipley’s “One Toke Over the Line” was indeed playing on the convertible stereo while the two drove to Las Vegas as chronicled in Thompson’s most famous book, Fear and Loathing In Las Vegas.

While writers (Hemingway excluded) mostly lead boring lives, Thompson’s certainly appeared like a constant good time. Yet the content on Discs 2 and 3—tapes from the most famous drugged-up Vegas road trip in history—make for sober listening. We hear Zeta-Acosta badgering a phone operator for an excruciatingly long period of time about where to find the “American Dream,” because a friend told him “if you’re in Vegas, look for the American Dream, ’cause that’s where you’ll find it.” And later on, we hear Thompson driving his white Cadillac convertible “with a beer in my hand” as Zeta-Acosta talks about the hotels they’re passing by.

Whether or not you read (or watched) Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, this is an exercise in tedium, because drug use is boring to observe. But it is interesting to hear the things Thompson didn’t exaggerate about Zeta-Acosta, such as his willingness to offer unsolicited, sage-like advice; “Trust your eyes, forget your heart,” he says when Thompson fears he’s too fucked-up to be driving.

Slogging through these discs makes you wish they had included a full written transcript of every word uttered. There is good material here, but it’s often a long, uninteresting listen to get to it. Finest example: a priceless recording from the early ’70s in which Thompson explains that he’s on vacation in Cozumel, Mexico, and went there to “cleanse my body and mind of speed.” Apparently his rare moment of sobriety gave him perspective, because what he mutters is completely out-of-step with his legend: “I would advise all future generations against using any type of mind-altering drug.” Come again?!? Sadly, the average human hasn’t the patience to sit through the five preceding tracks, in which he mumbles about an apparently unfinished “masterwork” he called Guts Ball. But alas, casual fans aren’t likely to fork over $59.98 for this collection to begin with.

If Thompson were a different writer and this were a different era, these recordings would have been purchased for $2 million and stored in the Harry Ransom Center for Literary Archives in Austin and pored over (with permission) by scholars and critics. They’d write papers on how in Gonzo journalism the tape recorder took the place of pen and paper, about the impact of sound and rhythm on his sentences, and how his writing might have been different had he taken actual notes.

But the most important thing they’d discover is the similarity between his everyday speech and his writing style. The Gonzo Tapes proves that Thompson spoke very literarily, something most writers are totally incapable of. The recordings Thompson made the one night he first snorted cocaine, for example, contain brilliant wordplay: “My mouth feels like the inside has been gnawed by muskrats…I experienced an episode of soaking sweats and great fear and anxiety.” Later he surmises, “I would not be inclined after this experiment to actively pursue a life constantly flavored by, or under the sway of, cocaine.”

But like Rick James said, cocaine’s a hell of a drug, and those scholars and critics would no doubt mark those recordings as the night Thompson began his long literary decline.