You may not have noticed, but we elected a few judges this summer. As usual, the races passed quietly. Of the 53 King County Superior Court spots up for election this year, only six were contested, and three of those were settled when one candidate got more than 50% of the primary vote. Forty-seven incumbents filed for and automatically received another term. All three state Supreme Court justices who are up for re-election also won in the primary. If you’re counting, that leaves three contested races out of a possible 56 for you to decide in November.

Judicial races are the ballot’s black hole, its flyover country. In fact, the backers of Proposition 1, the big Sound Transit package, worry about appearing on the ballot below the judicial candidates, as many voters traditionally call it quits upon reaching that list of unrecognizable names.

The irony is that judges can have far more direct and tangible impact on people’s lives than most anyone else you’ll vote for—deciding individual fates on a daily basis. Yet we hardly know anything about them. And that seems to be exactly what the legal establishment wants.

“The organized bar generally dislikes election of judges,” says Seattle attorney Michael J. Bond, who unsuccessfully ran for a Supreme Court seat this summer. “Most lawyers think the public is stupid and lawyers know best.”

Instead of a vigorous debate about the crucial legal issues of the day, judicial campaigns are largely bloodless and uninformative. Bar associations hand out ratings such as “Very Well Qualified” that do little besides remind you of those “Terrific!” stickers your teacher put on your homework in grade school. Candidates refuse to discuss anything substantive. And there’s rarely an open seat to prompt more vigorous contests. Most judges don’t wait until election time to leave the bench; they leave midterm, allowing the governor to select a replacement—who then runs as the incumbent.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia once wrote: “The first instinct of power is the retention of power, and, under a Constitution that requires periodic elections, that is best achieved by the suppression of election-time speech.” That perfectly sums up the state of judicial elections in Washington—and why it needs to change.

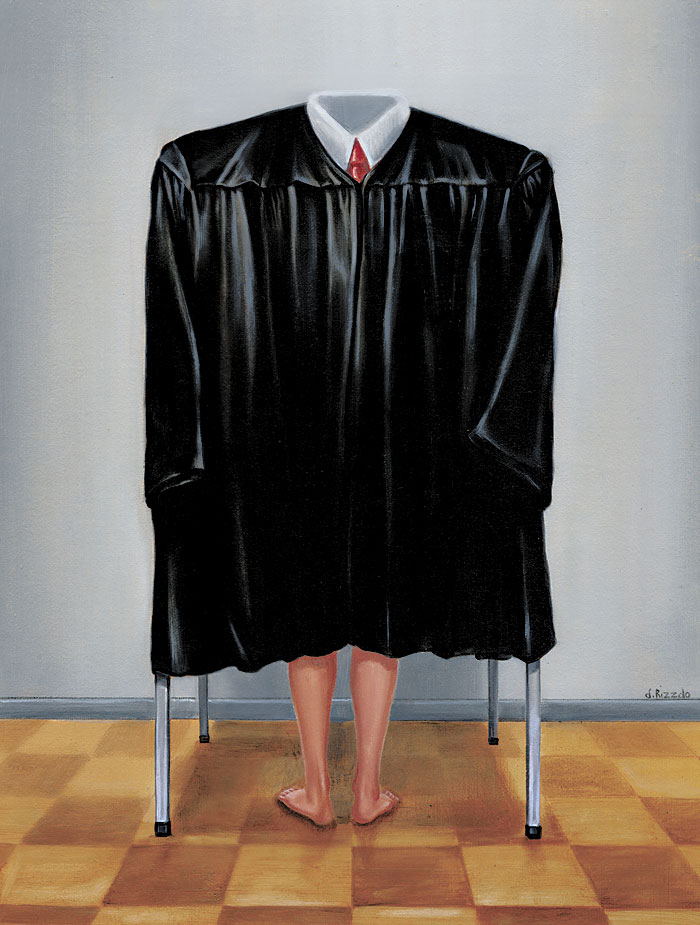

Former Washington Supreme Court Justice Phil Talmadge told The Seattle Times in 2006, “I want my judges to be just as the robes are supposed to symbolize—a blank slate.” This desire is consistent with the traditional model of judicial elections: genteel affairs in which candidates tout their character but not their views on the law, lest they appear to be biased or demagogues. The culture is underscored by Canon 7 of the Washington Code of Judicial Conduct, which prohibits “statements that commit or appear to commit the candidate with respect to cases…or issues likely to come before the court.”

But that prohibition has been used to justify a blanket refusal to engage in substantive discussion. “When it comes to [commenting] on specific issues or even old cases, you come closer to the line, and may even cross it,” says Michael Spearman, a former King County Superior Court judge who ran for the state Supreme Court in 2002. “The better course is simply not to put yourself in that position.”

“I think sometimes these canons are used as a pretext not to talk about what you believe,” says Washington Supreme Court Justice Richard Sanders, who is known for being outspoken on the campaign trail. “Maybe incumbents think that they can get more votes by not giving people a reason to oppose them.” Asked if he would call it a dog-and-pony show, John Strait, a legal ethics professor at Seattle University Law School, says, “It’s worse than that. It’s as though we tell voters, ‘There’s a dog-and-pony show behind this door. Trust us.'”

Where candidates in other branches of government discuss issues and philosophies, judicial candidates tout their integrity and invoke their credentials, endorsements, and ratings of qualification, as if those should suffice. It’s reminiscent of the Saturday Night Live sketch in which an insecure middle manager played by Will Ferrell attempts to assert his authority and quash dinner-table dissent by declaring, “I manage 49 people! I drive a Dodge Stratus!”

Like the virgin bride, the blank-slate judge is a counterproductive fantasy whose time has passed. The legal academy abandoned the idea that judges can simply mechanically apply the law more than a century ago, when a young mustachioed jurist named Oliver Wendell Holmes called bullshit on an old bearded one named Christopher Columbus Langdell. To pretend that highly experienced candidates haven’t formulated strong opinions on the law and the act of judging is a farce. “Every sitting judge or justice has a judicial philosophy,” says Sanders. “They are predictable, depending on how well you know them or research them. We have patterns of thought that we repeat. Everyone has an opinion.”

Yet today we ask judicial candidates to pretend that they haven’t developed such opinions, so as not to give the appearance of favoritism or commitment. Why shouldn’t a judge be able to opine generally but rule specifically? If we’re going to trust voters to select judges, why shouldn’t we trust them to make informed, responsible decisions?

“The current way of regulating judicial elections is unrealistic,” argues Sanders. “It propagates a myth that someone who has personal opinions cannot be a good judge.” Sanders is in favor of scrapping the whole regulatory apparatus, minus campaign contribution disclosure rules. “I’d even repeal the prohibition against announcing how you’re going to rule in advance. If a candidate already knows how he’s going to rule without knowing the facts, having read the briefs, and having listened to the arguments, I want to know that. Because I’m not going to vote for that guy.”

Sanders, who was first elected to the bench in 1995, campaigned on a libertarian platform of individual rights. [The sentence has been changed to reflect that Sanders was first elected in 1995, not 1998.] Contrary to election opponents’ fears of law-and-order demagoguery, he spoke out forcefully in favor of the rights of criminal defendants. His Web site features articles and speeches in which he details his thoughts on a number of legal issues and provides critiques of recent rulings and legislation. Seattle attorney Bond ran a similarly substantive campaign, arguing that the judiciary’s role is “to protect the people from the power of government and vested interests.” He maintained a blog in which he criticized his opponent Mary Fairhurst‘s rulings and answered voters’ questions in the comment threads. Neither Sanders nor Bond was accused of violating Canon 7.

The lack of information available to voters became most visible in 1990, when a relative unknown named Charles Johnson won a seat on the state Supreme Court despite running a quiet campaign. Many speculated that Johnson won because he shared a name with both a Tacoma newscaster and a popular King County judge, and because his opponent, the sitting Chief Justice, was named Callow. Johnson, who won the August primary, is widely considered a solid justice, but his ascension to the bench ruffled the feathers of a legal establishment that had been accustomed to seeing incumbents benefit from higher name recognition than challengers.

To remedy the situation, a number of groups recently banded together to sponsor the Web site VotingForJudges.org, which serves as a clearinghouse for information about candidates. It’s clear, user-friendly, and admirably thorough in its aggregation of the available information. Where it suffers is from a lack of decent information to aggregate.

Candidate statements are short and not terribly informative. (You’ve seen one Dodge Stratus, you’ve seen ’em all.) So what’s left for voters to base their choices on? Endorsements and ratings. Broad, nonpartisan groups like the King County Bar Association and the Municipal League aim to rate candidates’ fitness for office irrespective of ideology. Smaller, more focused groups, like the Washington Association of Prosecuting Attorneys or the Washington Conservation Voters, have a more transparent agenda and are likelier to favor a candidate based on his or her tendency to rule a certain way.

All these ratings systems suffer from a lack of explanation. It’s as if all you got were Roger Ebert’s thumbs-up or thumbs-down, with no review to accompany it. At best, a rating of “qualified” from the KCBA or the Municipal League is testimony to a candidate’s ethical and relatively courteous behavior, baseline of experience, and willingness to keep his or her rulings within what famous jurist Richard Posner calls “the zone of reasonableness.” But that hardly gives you much basis for a choice between candidates.

To get a feel for how wide that zone is, consider that state Supreme Court Justice Fairhurst, who famously argued that Washington’s Defense of Marriage Act prohibiting same-sex marriage violates the state Constitution, was rated “exceptionally well qualified” and “outstanding” by nonpartisan services. Now consider that Antonin Scalia—who thought striking down Texas’ prohibition of homosexual sodomy might lead to Constitutional rights to bestiality and masturbation—would likely receive the same rating.

Similarly, ratings of trial court judges won’t tell you anything about their approach to setting bail, a daily decision that “has a huge influence on whether a defendant decides to plead guilty,” says Scott Carter-Eldred, a public defender with The Defender Association. A defendant who can’t make bail may accept a guilty plea to get out of jail and return to his or her job, or may take out a bail bond and go into debt. A judge’s decision to set bail is based mainly on two factors: whether the defendant is a danger to the community, and whether the defendant is a threat not to appear for his or her next court date. But bail decisions are almost never reviewed, which gives judges a lot of discretion. “I want to know a judge’s approach to bail,” says Douglas Hiatt, a veteran defense lawyer (for whom this writer has worked in the past). “How do they decide when someone’s a danger? Is it just if they’re violent, or is it if they use drugs, if they’re mentally ill?”

At worst, the ratings are an indecipherable hybrid of competence and ideology. “I think they’re pretty phony,” says Sanders of the KCBA ratings. Seattle attorney Bond (“Well Qualified”), who unsuccessfully challenged Fairhurst (“Exceptionally Well Qualified”), says bar association qualification ratings have a value “next to zero. These are political entities.” Strait, who chaired the KCBA’s Judicial Screening Committee for several years, disputes the notion that politics is a factor. “If you could see behind closed doors, you’d find that it has a culture that is adamantly opposed to any kind of ideological test.”

To their credit, the KCBA and Municipal League publish their questionnaires and the candidates’ responses (one of the questions on the KCBA’s: “In 50 words or less, describe your judicial philosophy.”). They also seek out references, and not just those cherry-picked by the candidates. (Unfortunately, these aren’t published.) The Municipal League even invites the general public to apply to help with the ratings process. Nevertheless, there is no way to know how the groups got from the questionnaire and the references to the rating. The voting public is once more left merely to trust the experts.

Washington State has been conducting judicial elections for over 100 years. Twenty-nine other states do it as well. After all, why should one-third of our government be unaccountable to voters? And why should the other two-thirds be responsible for choosing those who would check their power?

By contrast, federal judges are appointed by the President and serve for life, like nobility or herpes. The idea—first advanced by Alexander Hamilton—is that job security, coupled with high-thread-count robes like the Arbiter H-178 (Murphy Robes, $230), will insulate jurists from political pressure and enable them to worry only about making correct rulings, popular or not. Judges are tasked with, among other things, protecting the rights of individuals and minorities; the correct decision isn’t always popular, and a judge should neither lose his or her job for ruling correctly nor rule incorrectly to keep it.

Judicial elections have done their part to validate Hamilton’s concerns. Several studies have indicated that judges tend to rule against criminal defendants and in favor of in-state litigants as re-election approaches—something commonly referred to as pandering. There’s also evidence of favoritism toward campaign donors. And on the anecdotal level, there’s Alabama. In 1994, Karl Rove targeted the state’s Supreme Court for a Republican, business-friendly makeover, employing high-level fundraising and, reportedly, a whisper campaign insinuating that his candidate’s opponent was a pedophile. In 2007, the state’s eight Republican Supreme Court justices, who had received a total of $5.5 million in campaign donations from ExxonMobil, threw out a $3.6 billion judgment against the oil behemoth.

In Washington, the group that has done the most to attack the traditionally dormant and nonpartisan nature of judicial races is the Building Industry Association of Washington, which aims to expand private-property rights. A red organization in a blue state, the BIAW heavily backed former Tim Eyman lawyer James Johnson for state Supreme Court. Johnson lost in 2002, then won in 2004, spending more than three times as much as his opponent, Mary Kay Becker.

The BIAW was even more aggressive in a 2006 race between incumbent Chief Justice Gerry Alexander and BIAW-supported challenger John Groen. With newly passed campaign contribution limits kicking in, the BIAW funneled its money into political-action committees that ran advertisements characterizing Alexander as senile and soft on drunk driving. Several Democrat-friendly PACs countered with their own ads on behalf of Alexander, whose campaign manager said that Groen “attempts to avoid compliance with any law he does not like.” Despite being outspent, Alexander won the race. [The story has been corrected since it was first posted to reflect that it was Alexander’s campaign manager who made the comment about Groen, and not Alexander himself. The quote has also been slightly corrected.]

The BIAW encountered significant backlash for its tactics and stayed out of this year’s races. “I think they realized they did more harm than good,” says Strait. Though the homebuilders’ lobby won’t have a court to kill the Growth Management Act anytime soon, it may have killed gay marriage: Along with Sanders, James Johnson went out of his way to trash gay marriage in the court’s 5-4 ruling upholding the state’s Defense of Marriage Act. His ’04 opponent, Becker, is perceived as being more socially liberal.

The reaction to the Alexander/Groen race demonstrates that it’s not a lack of information so much as a disturbance of the old order that irks the legal establishment. When an incumbent is challenged or attacked with ads that would hardly raise an eyebrow in the other branches of government, look for a firm and loud response from the organized bar. When a challenger with a substantive platform drowns in the apathy of judicial campaign culture, while the incumbent opponent coasts on endorsements and ratings and offers nary a peep of a defense of his or her record, nobody seems the least bit concerned.

Since the Alexander/Groen race, we’ve seen the creation of a new judicial campaign watchdog group, led by William Baker, a former judge in the First District Court of Appeals. Like the KCBA’s Fair Campaign Practices Committee (pdf), the Washington Committee for Ethical Judicial Campaigns (pdf) has no legal authority, but uses the carrot and stick of publicity (good and bad) to attempt to get candidates to sign its pledges and renounce campaigning that the group deems misleading.

This year, Baker’s committee condemned a mailer accusing Appeals Court Judge J. Robin Hunt of “a record of hiding the truth” in her open government rulings, but deemed a fundraising letter in which Hunt called her opponent “a threat to the cause of injured people” and “a tool of the BIAW” OK. The letter “was not alleged to be inaccurate in any way,” explains Baker. “It was from a group of lawyers to a group of lawyers, so there was not much chance that anyone was going to misunderstand that it was indulging in hyperbole for fundraising purposes.”

Meanwhile, the Fair Campaign Practices Committee warned against the practice of lower-bench candidates implying incumbency on the higher bench they’re running for by referring to themselves as “Judge” or wearing judicial robes on their yard signs. (The former is a ploy that can be ethically used only by one famous Mr. Reinhold, as the sitcom Arrested Development has shown.) Such heavy policing of lightly disputed campaigns has the feel of hiring hall monitors for summer school.

“The end result,” according to a 2002 paper on Washington’s judicial elections by David C. Brody, “is that a small minority of the electorate, many of whom do not have a rational basis for their vote, often decides contested judicial races.” The success or failure of multi-county, non-statewide ballot measures (which appear last on the ballot) is sometimes pinned on how many voters give up when they hit the judicial section. Dropoff averages around 25% from the big races like senator, president, and governor to the top appellate races. And it continues as the ballot moves to the Superior and District Court races, where, with the possible exception of small towns, voters frequently have never heard anything about the candidates.

The solution isn’t clear—as Baker points out, educating voters on the potentially dozens of lower-ticket judicial races in King County seems next to impossible. And there have been plenty of examples in other parts of the country of highly contentious, issue-filled judicial elections creating disillusionment. But the Washington judicial race that’s had the least dropoff in the past eight years? The 2006 contest between Gerry Alexander and John Groen. It says something about our approach that the race that most engaged the electorate is viewed as the worst-case scenario.

While expressing respect for the intelligence of voters, Baker confesses that he thinks judicial elections “are not a very good idea” and that he retired early to allow his replacement to be appointed. He supports “robust debate,” and notes that his committee plans to provide comprehensive, nonpartisan performance evaluations of sitting judges to help inform voters. But, he adds, “I think the Constitution allows for and must allow for some limitations on judicial campaign comments. Unless you want a judiciary that has public support only by the 51% that voted for the judge.”

When you stop to think about it, it’s hard to see why the legal establishment would ever want to open up elections. Why should those relied upon as counsel in the appointment of judges and who call the shots in sham elections want to cede their role to an apathetic, uneducated, and potentially reactionary electorate? Better to retire early and keep the selection process in house.

The story’s not that simple, of course. The bar is also trying to look out for the powerless—the criminal defendant who will plead guilty if he can’t make bail, the gay couple looking to make a civil-rights claim in a deeply conservative region. But beneath that rationale is the assumption that the public can’t distinguish from demagoguery.

You can learn a lot about someone by looking at their bookshelf. According to a 2000 study, the second most-cited book in legal scholarship was Law’s Empire by Ronald Dworkin. Beyond claiming for the field an empire, the book features as its protagonist an imaginary super-judge named Hercules.

The title of the most-cited book? Democracy and Distrust.