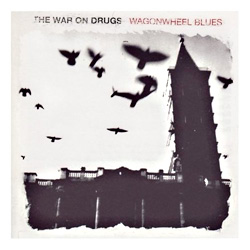

The War on Drugs Wagonwheel Blues (Secretly Canadian)

We’re only halfway through 2008, but Philadelphia’s The War on Drugs claims one of this year’s most exciting debuts. On Wagonwheel Blues, songwriter Adam Granduciel precisely fuses together the best elements of rollicking folk and classic rock with experimental ambience and post-punk deconstruction. The disc coalesces shades of Dylan, Springsteen, Sonic Youth, and the Velvet Underground into a uniquely visceral musical reverie.

Several swirling instrumental moments pepper the album’s 45 minutes, conveying the record’s intricacies and emotional resonance. But Granduciel’s road-trip narratives, buoyed by textured arrangements rooted in harmonica, organ, and layers of guitars, are the driving force. Opening track “Arms Like Boulders” is a Dylanesque loose blues romp, while on “Taking the Farm,” Granduciel channels the Boss over locomotive percussion and droning keyboards. Daydream Nation atmospherics wash throughout “There Is No Urgency,” Granduciel’s reedy, trembling voice warning, “There’s trouble down here, there’s trouble down there, there’s trouble everywhere.” Trouble never sounded so inviting.

Though The War on Drugs seemingly came out of nowhere, many of these songs were recorded at various points over the past few years. Nevertheless, Wagonwheel Blues feels unified, the product of dingy, beer-stained American rock tradition and progressive experimentation. JONAH FLICKER

CSS Donkey (Sub Pop)

“Your mouth is stuck to a thousand fags,” cheerfully raps the one known as Lovefoxxx at the end of the one called “Jäger Yoga.” And this is Cansei de Ser Sexy’s serious album. No, really—next song’s about spousal abuse. But fuck the heck, you guys: No one knows what to do with CSS. Not Sub Pop, not Apple, not proponents of, uh, “nu-rave.” I guess we’re supposed to dance, guiltily: “Let’s Reggae All Night” has a nice locked-in squelch to it, but I wish the line I heard as “let’s break the bed in half” wasn’t actually “break my back in half.” Which prompts the question: Does this band even get its own shtick? Why did they call the album Donkey? Why does “Reggae All Night” have nothing to do with reggae? And why did they sandwich it between two Sleater-Kinney-style one-finger new-wave riffers? “Life is just too serious,” complains the best song (“Give Up”), which makes me feel a pang of guilt. This is one of those unquantifiable litmus-test groups for sticks-in-the-mud, like the Go! Team, where you feel bad kicking dirt on some kid’s sand castle. However ill-conceived their tinny beats, swiped hooks—”Rat Is Dead (Rage)” grooves on a chuggy Hives riff—and questionable “fun” quotient, these dance-punk displacements here present a tuneful, synth-shined step up from their more annoyingly hit-or-miss debut (which began with a chant called “CSS Suxxx”). But their newfound tastefulness comes at a cost: less personality, annoying or not. Where song titles once delivered concrete jokes (“Meeting Paris Hilton,” “Let’s Make Love and Listen to Death From Above”), sometimes in not-so-concrete English (“Fuck Off Is Not the Only Thing You Have to Show”), they now read like tracks from any generic-alt hangers-on: “Give Up,” “Left Behind,” “I Fly.” Maybe they are generic-alt hangers-on. But their bid for a career is at least as good as, say, Santogold’s. “You’ve gotta get your move on”—who can argue with that? It’s called Donkey, eh? Just go with it. DAN WEISS

Nas Untitled (The Jones Experience/Def Jam/Columbia)

Since his classic debut, Illmatic, Nas has been mostly coasting on his charm, his gift for public relations, and his skills as an MC. But on Untitled he’s clearly hoping that by name-dropping big issues (reparations, single motherhood, media control) and dazzling you with his acrobatic flow (“I’m over they heads/Like a bulimic on a see-saw”) you’ll gloss over the fact that he’s not saying anything coherent. Credit Nas for understanding that relevant pieces of art should speak to big things, and indeed Untitled—partly through its original title, Nigger—takes on the incendiary intersection of politics, race, and language. But bits of intelligent rumination are overshadowed by hypocrisy: Nas speaks of inclusion while paying tribute to Louis Farrakhan and decries poverty while glorifying materialism. One can’t help but conclude that the rapper chooses his subject matter simply for its shock value. (What will he call his next album? Nazi? Abortion?) Even the songs that should be slam dunks—like the Murdoch-critiquing “Sly Fox”—clank off the rim with erroneous claims like “they own YouTube.” (No, that’s Google.) “I am tuned in,” says an ominous voice later in that song. So are we. Nas has a forum, passion, and talent. Too bad his message is muddled. BEN WESTHOFF