On first glance, Georgia’s Dark Meat fits snugly into underground rock’s current zeitgeist. Like Feathers and Espers and all them other hairy freak-folkies, they’re a large quasi-hippie ensemble wrapped in a cultish aura. All 17 or so members are known formally as Dark Meat/Vomit Lasers Family Band/Galaxy, a name consciously modeled after Parliament-Funkadelic’s love for cozmic-trickster nomenclature. Even better, they tour the country in a silver bus retrofitted with beds, a bathroom, and a kitchen nook. The 1972 relic, purchased on the side of the road just outside Atlanta, even boasts green ‘n’ yellow stripes and a painting of an eagle landing atop a mountain.

So yeah, those People’s Temple/Merry Prankster vibrations are unmistakable.

“We’re very much a real collective,” explains bassist and co-founder Ben Clack. He’s phoning from the bus, which the current driver has just now pulled off the interstate at the North Carolina–Virginia border—unexpected brake problems. A bandmate up front suddenly shouts: “EVERYBODY OFF THE BUS.”

“We might have an emergency here,” warns Clack. “But anyway, we pretty much live together by touring six months or so a year. We all live in five or six different houses around Athens that are all within a few miles of each other.”

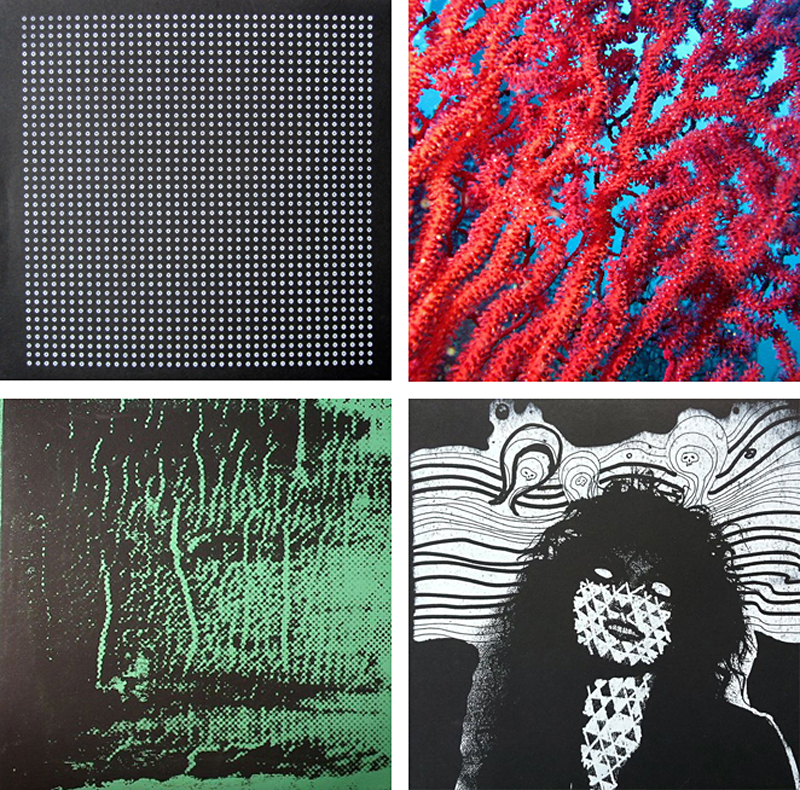

Yet Dark Meat also resembles those weirdos in Lightning Bolt and Friends Forever in the way their live shows are art-punk spectacles torn from the pages of the most acid-fried comic books imaginable. Neon costumes and all manner of day-glo stage ephemera swirl about like a drunken kaleidoscope. In fact, very few fans of noise-rock would’ve scratched their heads had Lightning Bolt’s label, Load Records, released Universal Indians, Dark Meat’s 2006 debut.

There can be no doubt that all these avant-shenanigans have exerted a significant influence on the band. Dark Meat’s inner core, as Clack points out, is a bunch of hardcore record nerds in love with obscuro-sounds both modern and old. But the way these sounds are filtered is where the group’s uniqueness really shines through. Dark Meat, unlike the overwhelming majority of freak-folkies and noise-rockers out there, is a band of down-home Southerners. And as is the case with nearly every underground musician from the South since the ’60s, they remain forever tethered to their roots: rural rock and roll, Delta blues, New Orleans jazz, and country twang.

“We feel like a Southern band. That’s who we are. And I love it,” says Clack, now standing beside the bus along with everybody else. “I think the South is a wonderful place. It’s just a fascinating culture. We live in the fuckin’ woods. We live in the middle of nowhere. That’s where we’re from. That’s the way we like it.”

Clack then compares Dark Meat, which started out as a Neil Young cover band, to the Allman Brothers (circa ’69, of course), as well as free-jazz saxophonist Albert Ayler, who hailed from Cleveland (a town the bass player calls “very Southern”). Both, he explains, were playing, “free shit, but coming at it from traditional roots music that everyone recognizes. I feel like that’s what we’re trying to do, too.”

After repeated spins, Universal Indians (which Vice has just reissued) reveals this intent. The disc, full of hyper-charged Stooge-rock (front man and guitarist Jim McHugh even wears a pair of Ron Asheton shades), is as punishing and claustrophobic as anything from Comets on Fire or Dead Meadow. Certain tracks, including “There Is a Retard on Acid Holding a Hammer to Your Brain” and “Assholes for Eyeballs,” even recall the twisted psych-punk of vintage Butthole Surfers. Yet despite such gnarly song titles, Dark Meat are no sonic primitives. A full horn and string subsection, the Vomit Lasers, can howl like a Dixieland band on PCP or bust airtight funk as if they’re augmenting Booker T at a Memphis nightclub in 1964.

The same goes for the Sub Tweeters and Key Bumps—respectively, Dark Meat’s backup singers and percussionists/flag corps. Both subsections of the large outfit help transform Dark Meat’s wild-ass stage show into a kind of post-apocalyptic Mardi Gras. On record, however, they serve as key musical components, infusing the band’s manic rock and roll with authentic white gospel ecstasy. The Sub Tweeters in particular exude more soul than most modern R & B pinups.

Ultimately, Dark Meat is that rare band that can sum up the entire history of rock and roll in a single song, erasing divisions between subgenres with every howling riff. They can venture from wildly experimental to stone-cold classic and make it all sound so damn natural.

According to Clack, this ability to “put it all together” is another Southern trait. And while that’s certainly true, it also makes Dark Meat a truly democratic band at a time when democracy in America is a hard thing to come by.

So get on the bus…once it’s fixed, of course.