You can be forgiven for never having heard of Brad Walker, but the former University of Washington star’s name is one you ought to remember next year, at the 2008 Olympics in Beijing. The Mountlake Terrace resident won a gold medal in the pole vault at the world track and field championships earlier this month in Osaka, Japan. He earned the silver medal at the 2005 event, after failing to make the Olympic squad in 2004. Thus, having steadily improved since graduating from UW four years ago, he’s now a favorite for Beijing.

So how come Walker’s such an unknown in his hometown? Speaking by phone fromZurich before the super-prestigious Weltklasse meet on Sept. 7 (where Walker placed fourth), the 26-year-old says, “As an NCAA champion, I would receive significantly more press than I do as world champion. I definitely don’t get recognized in the Seattle area. I leave Seattle [for Europe]…and people come up and shake my hand and ask if I’m the world champion.”

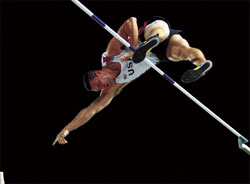

Walker won the gold in Osaka with a vault of 5.76 meters, and his current personal record stands at an even 6 meters, or 19 feet, 8 inches (that’s the equivalent of three Hummer H2s stacked on top of one another). His 5.95-meter vault in Australia this past spring is tops in the world this year. Incidentally, the world record of 6.14 meters by Ukraine’s Sergei Bubka—generally considered the greatest ever in his sport—is now 13 years old, and longoverdue for breaking.

Unfortunately, says Walker, his chronic back problems (bulging discs) will likely prevent any new personal records this season. Two years ago, he missed the landing pit after a jump in Russia, hitting his head and briefly conking out. That, plus the grueling training the sport requires, means “you’re in pain as an elite athlete most of the time,” he adds.

And unlike a gimpy player for the Seahawks or Mariners, managing that pain—and one’s medical costs—is the responsibility of the individual. “If your world ranking’s high enough,” Walker explains, “you do get a little bit of support. We basically have insurance that covers non-athletic-related injuries. A lot of money, and I mean a lot of money, is spent to keep yourself healthy—massage therapy, chiropractic, acupuncture, seeing doctors. It’s a significant cost that all athletes pay out of pocket. You basically look at it as return on investment. If you’re not healthy, you’re not making money. You sometimes have to suck it up and swipe the credit card more than you like to get the treatment that you need.”

On the revenue side, he explains, “There’s appearance money on the line for most of the places you go to. If you’re No. 1 in the world versus No. 10 in the world, there’s a hugediscrepancy in the money you make. That being said, this has been my sole job. There’s a lot of people who aren’t that far down the totem pole who are working at Home Depot.”

This is why American track-and-field pros live like gypsies. Says Walker, “We need to make our money over in Europe,” where significant TV coverage makes the sport financially viable. “It’s a long season. Almost a third of the year I could be gone for any given time.”