For a musical that strove—with unprecedented vigor—to be timely, to tackle contemporary issues, West Side Story has held up magnificently 50 years after its premiere. The subtexts of immigration and racism are as relevant as ever, of course. Love and hate, mistrust and misunderstanding, are eternal; and even the elements that most risk seeming dated—the dance music and the daddy-o slang—don’t. Nor has the show become a Grease-style exercise in camp nostalgia. It’s proof of the work’s strength that it remains fresh even in a staging specifically intended to re-create Jerome Robbins’ original, as the 5th Avenue current anniversary production is. Under director Bill Berry, this is a live, sweating, bleeding West Side Story, not a reverent museum piece.

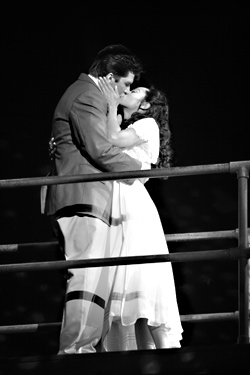

The production is less successful, though, at realizing the show’s balance (again, unprecedented) of comedy and tragedy, pathos and exuberance. There’s a certain breadth missing here, almost as if they’re wary of the work’s gravity, that keeps it from being something you can fully immerse yourself in. It’s an issue of pacing; there are moments that ache to be more expansive, like the “Tonight” balcony scene, which needs time to blossom, and the rushed final death scene. (They might also rethink that gunshot; the startled audience giggled nervously as Tony lay dying in Maria’s arms, and only fully calmed down after he was gone.)

There’s something hyperkinetic about Maegan McConnell’s Maria in particular, a certain shrillness she never sheds, though she does mesh believably with Louis Hobson’s fantastic Tony: at once idealistic and romantic, street-smart and gutsy, charismatic but never slick. His likability projects easily, as does his voice, which has an unpolished boyishness perfectly in character. Manoly Farrell brings Anita a glowing, coiled energy, combusting with Miguel A. Romero’s suave, smoldering Bernardo, but both cast slightly darker shadows as well: a weary, seen-it-all emotional weight that’s a good example of the sort of thing the production wants more of. Most affecting of all is Seán G. Griffin’s elderly Doc, played exactly on the mark, despairing to see yet another generation repeat the same old mistakes.

–G.B.

Too old to be contemporary, too young to be historical, West Side Story represents a time that we think we remember clearly but no longer inhabit. When this anniversary production gets close to the works thematic elementsthe grind of poverty, the distrust one immigrant population has for the group following them, the volatile combination of hope and frustration that is adolescenceit erases whatever awkwardness time might have created and justifies the efforts put into resurrection. Choreographer Bob Richard worked with Jerome Robbins on the latters last revival of West Side Story; in an uncertain dance world, this is the closest that we will get to the original material.

Most contemporary audiences know the musical from the 1961 film, but its arcing New York City crane shots and the in the middle of the action dance sequences arent a part of the theatrical production. Instead we see the world of the Sharks and Jets as an enclosed space, with the front curtain replaced by a chain-link fence that literally makes the stage into a kind of jail. Instead of spreading out, this production stacks up layers of people and their problems, making the gangs desire for their own inch of turf into a visceral reality. The moments that read the best are the ones that play on this sense of compression: the tight shoulders and intricate footwork of the mambo in the Dance at the Gym are a kinetic translation of the Puerto Rican gangs anger and desire, but the Jets goofy chicken-necked gymnastics in response are historically accurate but not as evocative. Even less convincing now is the wishful thinking Somewhere, with a ballet-tinged lyricism that looks more like Agnes deMilles contributions to Oklahoma. Robbins did urban much betterthe more grit involved, the more believable it is.

–S.K.