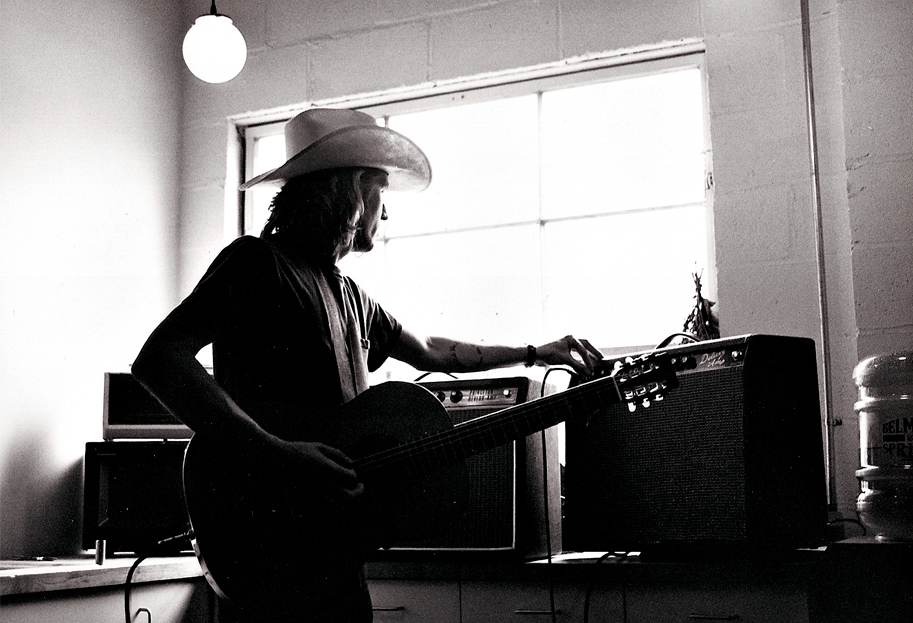

Gerald Collier’s career commenced with shiny power-pop outfit Best Kissers in the World, but it was the devastatingly dark and beautiful solo work he did in the wake of that band’s demise that made him one of the most important singer-songwriters the Northwest has produced. His inimitable ability to mix pathos and wicked humor with honest, utterly humane insights about love, lust, grief, and vice should have put him in the same class as Kurt Cobain. Collier took the lessons of Lennon to heart as much as our patron saint–he just never received as broad a platform.

That incisive and occasionally disturbing wit first revealed itself in 1996 on his now-out-of-print solo debut for C/Z Records, I Had to Laugh Like Hell. Shortly after its release, Collier hooked up with a perfect storm of collaborators: guitarist William Bernhard, bassist and vocalist Jeff Wood, and drummer John Hollis Fleischman. Despite the presence of an undeniable chemistry, the band only lasted a couple of years, eventually imploding under the stresses brought on by a sour major-label deal with Revolution Records and Collier’s self-admitted struggles with his notorious temper and ego.

Nearly a decade later, thanks to the release of How Can There Be Another Day?—a collection of B-sides and live performances lovingly resurrected and restored by Bernhard—that original lineup of musicians will share a Seattle stage again for a one-off reunion show. What follows is an oral history of that unforgettable time, told in the words of the players, producers, and people surrounding them.

Gerald Collier: Bill [Bernhard] had been after me for a year or so just to come over and play with his band; he was really into the idea of his outfit backing me up. I had just come off Best Kissers in the World and really didn’t want to do a full-blown band thing. I kept saying no . . . no . . . no . . . no. I was tired, deaf, and was really into being quiet at the time. I just assumed that they were, well, I don’t know, loud, I guess.

Jeff Wood: I’m a sucker for a clever turn of phrase, a vivid picture painted with few words, and Gerald’s got that talent in spades. A potent blend of smart and smart-ass that spares nothing and no one. I listened to Gerald’s first solo record, I Had to Laugh Like Hell, nonstop to get ready for our “audition.” Not only were the lyrics great, but the music really got me, too. Fantastic songs with undeniable melodies. Harmonies just began popping into my head. I couldn’t wait to give it a run.

Collier: One night I agreed to come over and was just blown away at how dynamic they were. It didn’t hurt that they knew my stuff inside and out as well. It was just a magical thing. It was something that I just couldn’t walk away from.

Wood: We got together with Gerald one night in the basement, played the songs, and realized that there was some serious mojo at hand. The mood in the room was more like we were all discovering a band rather than joining one.

William Bernhard: I really loved I Had to Laugh Like Hell, and my band at the time, the Superstitions—which was composed of Wood, Brandon Milner, and myself—used to do shows with Gerald and Marc Olsen during that time period [Editor’s note: Fleischman later replaced Milner on drums]. I could really hear our sound couching Gerald’s songs. He was skeptical at first, but I bugged him about it till he was willing to try us out. After we finished the first song, we all looked at each other and realized, “Holy shit—we’re onto something.” It was magic. We played our first show three weeks later.

Don Yates (KEXP DJ, programming director): Best Kissers in the World was a fun power-pop band, but not terribly deep, which made his subsequent solo career all the more remarkable. The guy fronting the short-lived and somewhat shallow power-pop band was all of a sudden a dark singer-songwriter of considerable emotional depth and melodies to die for.

Barbara Mitchell (publicist): [C/Z Records owner] Daniel House gave me a copy of I Had to Laugh Like Hell, and I freaked out over it and made him let me do publicity for it at no charge. Gerald just had that special “something” about him that appealed to me. He’s an amazingly intelligent guy who has a way of putting things into words that is simultaneously funny, poignant, and sarcastic.

Stuart Hallerman (engineer): Gerald’s songs were well-formed and full of lyrical wit. He told of characters in seemingly real lives, with a story in each song. Mini–Raymond Carver tales.

Mitchell: I can’t alchemize chemistry into a handful of words, but I can say that every single person I dragged out to see those four people play music together came back to me utterly floored.

Collier: Aside from the fact that they were lightning fast and damn near perfect in the studio from take to take, they were really nice guys with no pretension at all. They made me a better player.

Dave Dederer (engineer, musician): This is stuff that sounded good when it was done almost a decade ago, sounds good now, and will still sound great in 20 years. For me, music is all about those serendipitous moments when the right people come together at the right time and the resulting whole is greater than the sum of the parts—something amazing and transcendent happens. These recordings document one of those rare moments.

Johnny Sangster (engineer): I think the group had mutual respect for one another, but it was clear who the star of the show was. Gerald could be impatient with his bandmates. I remember him having a big personality, very charming with an undercurrent of “don’t fuck with me.” At one lunch, he was telling about a girl he knew who had told her girlfriend not to get involved with him because he was the devil. Maybe I’d been watching too many X-Files, but it seemed strangely possible.

Wood: Gerald had a quick fuse and an acid tongue, and even if you weren’t the target, it was nobody’s good time to be anywhere nearby.

Collier: I’d like to think that [the band breaking up] . . . well, I know why. It was all by my hand. We had come back from a mini-tour that was more than a little strange. I recall driving all night through snowstorms in Montana or Idaho just to play for six people at an art opening that was canceled because of the weather. You know, crap like that. It was surreal. The guys were not sure of their future with me and were justifiably getting concerned. The bookings were not getting better, and it seemed to everyone that something was wrong. Things were flat. You could just feel it. I was the only one without a job at the time, and they were being paid meagerly at best. They were juggling day jobs, touring schedules, and waiting for things to get better. They never complained once, just played their asses off every show.

All the while, the label [Revolution] was set to release “Fearless” as our first single. I kept saying to myself: “We just need to hold on, everything will work out.” Storm clouds were on the horizon with Revolution. I kept getting these messages that all was not well and that they were going to fold. The person who signed me there was a president, was on some shaky ground, was going through a psychotic meltdown stemming from pressure from the top, etc., etc. I did my best not to let on. With that said, when Jeff, Bill, [drummer] Hollis, and I started playing together, I was the guy with the most experience. I had been through this before with the Kissers and MCA. I had made all the classic mistakes, and I was going to be sure that none of them got made again this time around. I was the leader. In my mind, that comes with a lot of responsibility. The band and those guys I looked at as a family, and they looked to me to guide the ship. I was gonna take care of my family no matter what. You see, I’m a VERY prideful guy. I also used to be VERY competitive, and I’ll be the first one to admit that I have one hell of an ego as well. I enjoyed the fact that I was able to take these guys on this “Major Label Ride.” I enjoyed the fact that the band were being recognized as great players when nobody would give them the time of day before. I was the guy taking the underdogs to the championship game, and we were gonna get that goddamn ring. I was the guy with the songs making it all happen. Ego, ego, ego. It made me feel good.

Well, when we got home from that tour the guys wanted to talk to me about things like pay, the future, and how things were going. You know, real things. Make no mistake. They were “green,” but they were all very smart and well-intentioned people, ya know? I just broke. I knew what was about to happen. I was going to be found out. I was not the great leader I had convinced everyone that I was. I was not going to be able to hold back the flood. But instead of confiding in the band the way they had always confided in me, I chose to burn the house down with everybody in it. For that there is no sympathy to be given. The truth is: I, at that time, would rather have flamed out under the circumstances than given my band the chance to make a decision to do what was best for their respective futures. I feared that they would leave me. I feared I would be left alone to suffer the indignity of yet another failure. Selfishly, cowardly, and dejectedly, I fired my family.

Wood: Despite the inferno that burned it all to the ground, I’d been willing to reconcile for a long time—to get an explanation, a mea culpa, and then call it a day. But that phone call never came, so I just filed it under “MIA” and moved on. I don’t like leaving things undone, and this was like a book with the last chapter ripped out of it.

Bernhard: When Gerald dissolved the band, I was the only one who didn’t get fired. I tried to stick it out, but Jeff and Hollis are two of my dearest friends, and their situation and feelings were killing me: I couldn’t sleep, I felt like shit. It was awful. Secretly, I was holding on hoping that Gerald would realize he’d acted rashly and reassemble everyone, but that never happened. I quit a month or two later and joined Sky Cries Mary.

Wood: When this demos project started to take shape, enough time had passed that when Bill mentioned doing a show or two to promote it, I thought it would be worth seeing if amends would be made. This band was way too close to have been able to do it otherwise. I’d continued playing with Bill and Hollis in varying degrees up until I moved to New York, but it was obvious that Gerald and I needed a “come to Jesus” conversation or three for this to really happen. The first of those lasted two hours, and through a lot of grace on both our parts, we buried a pile of the rusty hatchets that had been lying around the yard for the last nine years.

Bernhard: I am archivist of sorts; I kept all of our B-sides and demos stashed away, but hadn’t listened to them in years. When Gerald moved to Portland (I lived there for two years while my wife, Iris, finished medical school), we started hanging out. One night he told me that [indie label] In Music We Trust was interested in putting out his unreleased country album. At that point I told him I had at least one album’s worth of B-sides, demos, and live stuff from when we played together. A couple of days later, he came over and listened to what I had and said that, without a doubt, it should be compiled and released first.

Collier: I was thrilled to learn that he was thoughtful enough to have kept the stuff. I threw the shit in a river somewhere.

Yates: I think it’s a pretty impressive album—usually these types of B-sides, demos, etc., compilations are pretty spotty. Most unreleased songs are that way for a reason, but damned if everything on this album isn’t worth hearing, and some of the songs and performances are outstanding. And I’ve no idea why he’s never gotten around to making an official recording of his own “For Taking My Baby Away”—the demo version here is just stunning.

Hallerman: Everyone was very musical; it wasn’t hard to pour a little whiskey in ’em and roll tape. “Hell Has Frozen Over” and “Don’t Discard Me” happen to be about the best acoustic recordings I ever made.

Bernhard: I whittled through all of the recordings, at least two hours’ worth, and started creating a list of songs that seemed to make a solid album. After I had the final list assembled, I set about trying to find the master recordings because most of what I had was on cassette. I managed to unearth a lot of them, but not the core of the album: “Sorrow,” “Jigsaw Puzzle,” “Night Comes In,” “Rocket Man,” and “Sometimes She Forgets.” Those songs only existed on my hissy, shitty cassette. I tried cleaning them up in ProTools to no avail. We thought we might be able to clean them up during the mastering process, but it only made them sound murky. I almost pulled the plug on the project, but in a final act of desperation I e-mailed [Collier’s former manager] Danny Bland to see if he had what I was looking for. He did, and I was back in the mastering studio a week later.

Wood: I’m just really glad all these songs are finally seeing the light of day, though I rue “This One Is Already Gone” not making it onto the record. That was part of the incredible Avast! sessions with “Hell Has Frozen Over” and “Don’t Discard Me.” They were dubbed the “3 a.m. sessions,” as we referred to the mood and ambience and the music created in those days in that cinder-block cavern, with its magnificently out-of-tune piano and Stu Hallerman being perfectly droll at the desk. It always seemed like the middle of the night during those sessions.

Bernhard: Gerald stopped playing music for five years or so, and I was hoping that this project would inspire him to revisit songwriting. I told [KEXP DJ] Cheryl Waters about the “new” album and asked if KEXP would be interested in having him play on the air. They were really excited by the idea, and when I told Gerald he asked me if I’d do him a favor and play with him. I thought we should have a full band and told him that I wanted to ask Jeff and Hollis first because it was the right thing to do. He agreed. Needless to say, I was blown away. There’s no real grand design at work here; it just seemed like a cool, if not far-fetched, idea at the time.

Collier: I’ll never forget the phone call. He called me up, and it basically went like this:

Bill: “I have an idea—what would you say to getting the band back together to do some CD-release shows?”

Me: “Bill, there may be bad blood . . . um . . . I don’t know . . . Jeff lives in New York now.”

Bill: “I’ve already called them, and they are all in.”

Listen to a sample of Gerald Collier’s “For Taking My Baby Away.”