The scene opens with a grainy, out-of-focus shot of a sun-bathed coast cast in a red-orange hue. There’s not a cloud in sight. At the shoreline, waves are crashing and seabirds are flying in to feed. The wind is blowing, the tall grasses swaying. An attractive couple—a young man and a young woman—come into the frame, stare off, and say nothing. They could be lovers, they could be siblings. Either way, there is a strong connection between the two. Despite all the breezy motion and the subtle action, something is absolutely still about the shot. There’s not a sound to be heard.

Cue “Saltwater,” the opening track off last year’s self-titled debut from Baltimore duo Beach House. Its slow, fuzzy beat glides along, opening up to a twinkling, sweeping melody driven by a handful of vintage organs, caked in a gritty hiss, and the gentle words of a lucid vocal siren. “Love you all the time, even though you are not mine,” a woman sings. First you see the ocean. Then you feel it hit you like a wave. Then you hear it suck you under.

That voice belongs to Victoria Legrand, and it has ethereal qualities not heard since Naomi Yang (Galaxie 500/Damon and Naomi) and Hope Sandoval (Mazzy Star), two female vocalists whose ghostly ambience transformed slow-core into a movement. Legrand, who studied theater in college, is as powerful vocally, lyrically, and physically as her predecessors. But whereas Yang and Sandoval came from a time predating portable, instantaneous information, Legrand is spearheading a movement to help return the hyperspeed 21st century back to a period when slow times really felt slow, when technology didn’t allow us to have an obsession with immediacy, when life’s simple moments could be uninterrupted and taken in stride. As descriptive as they are emotional, the lyrics briefly tell the stories of first- and third-person characters, and it’s Legrand (either drawing from personal experience or her own theatrical background) voicing the character, the plot, and the scene.

The sounds of Beach House are washed and lightly brushed with visual delight, the picturesque audio equivalent of what a still-life watercolor painting, made by a kind old man in his Adirondack chair on the coast of Martha’s Vineyard in August, would be.

It’s fitting that the band first came together in 2005 during the late-night hours, during that perpetual state of slumber when the heart beats slower, and the only time that a majority of the outside world completely shuts down. With Beach House, there’s a lullaby in every story, where darkness and vibrant, starry fantasy interact.

“Once when I saw her there, white light she stood so still, in the hallway, they’re lying there, in the red blossom of the days” sings Legrand on “Tokyo Witch.” “I want your picture, but not your words.”

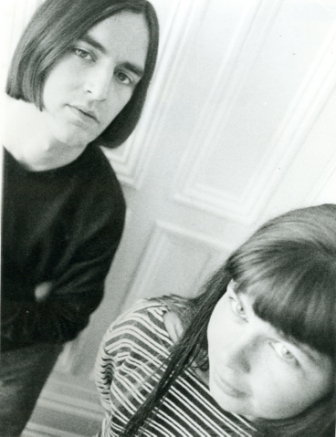

There’s an incredible energy between Legrand and Beach House’s multi-instrumentalist Alex Scally—his gentle, airy guitar tones (reminiscent of Mazzy Star’s guitarist David Roback) never feel detached from Legrand’s commanding voice or calculated melody, where the music is engaged with delicate simplicities. But unlike other musical duo/couples like Mates of State, who put their own relationship at the forefront of their music, Scally and Legrand have never been romantically involved with each other. They’re strictly good friends who connect through music.

Album closer “Heart and Lungs” evokes a grainy scene similar to the one playing during “Saltwater,” though it’s played in reverse, as if going from light to dark. The sights of the shoreline, the waves, the birds, the sand, the grass, the man, and the woman are slowly moving further away as we listeners drift out into the darkness of the sea, and the sounds of everything besides the music are instantaneously silenced.

Legrand sings, “From all eyes, the land disappears/All that is left is a hollow leg of tears.”

Fade to black. Roll credits.