The house is easy to find. It has an immense hedge, hot-pink trim, and a dilapidated 1969 Ford truck parked out front. It’s a standout even by Ballard standards. And it suits Joe Reno to a T. He’s lived in it since his family moved here from Everett in 1950, when he was 5 years old. Reno says he doesn’t need to go anywhere: “I travel with my mind.”

The house is full of art. No, make that overflowing with art. Prints and paintings cover the walls, but just as many are set directly on the floor. There are piles of etchings and block prints spilling off the tables, which, in turn, are surrounded by various vintage printing presses that take up the better part of what may have formerly been a living room. Reno tells me he recently got rid of his stove to make room for more storage. It doesn’t sound like he used it much anyway, preferring the gourmet meals of curator and critic Matthew Kangas, with whom he’s enjoyed hundreds of dinners in a friendship that dates to 1980. “Twenty-six years of gobbly gobbly gobbly, yum yum yum,” Reno says. He’s shown his appreciation to Kangas—whom he describes as a phenomenal cook—with a number of drawn pieces. Kangas isn’t alone in accepting Reno’s work. A number of collectors have known Reno since his Ballard High days.

“You barter much?” I ask. “You bet,” he replies. “Food, medical, dental bills….” He flashes me a winning smile.

Reno’s talk is casually peppered with the names of legendary Northwest arts figures, such as Morris Graves, who praised the young artist’s efforts when they showed together in 1967, and Guy Anderson, who owned a Northwest Coast Native American mask that served as the model for Reno’s drawing Guy’s Dog. (Anderson introduced Reno to the joys of Pernod as well.) Too young to be part of the Mystic School himself, Reno nevertheless has strong mystical leanings. He believes, for example, that American artists—and Northwest artists in particular—benefit from a psychic power emanating from our natural surroundings. His conversation is interspersed with two prominent phrases: “To make a long story short” and “What I’m driving at is this.” We rarely get there, but it matters not at all. His work, like his conversation, is a joyride. At one point, he spontaneously breaks into song. Complimented on his voice, he replies, “Oh, well, I was using that high one, but I have two better ones.”

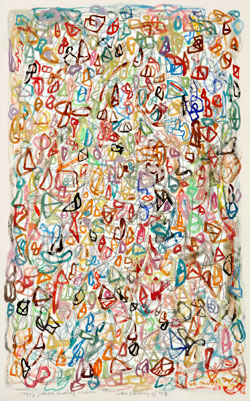

His art reveals multiple voices as well. “Joe Reno: Works on Paper Retrospective,” now entering its final week at the Kirkland Arts Center, displays about 50 prints and paintings from three decades of work, all of them owned by Kangas (the exhibit’s curator). They cover an impressive amount of stylistic ground. Figure Study (1996), for example, shows an almost calligraphic reclining female figure in egg tempera and ink that recalls Edwin Dickinson’s penchant for rapidly executed portraits done in a single sitting. (And no wonder: Reno studied with Dickinson in New York.) But more impressive are Reno’s abstract works, some of which playfully reproduce Mark Tobey’s “white writing” in color. (Wall Painting of ’48, done in 2000, is at left.) Other works, including a number of landscapes, exhibit an intense expressionism. Made up of shimmying lines in electric colors, Olympic Mountains, February, and Self-Portrait 12/30/96 reveal passion, frenzy, and unrest.

Reno embodies the creative pluralism of the Northwest while remaining a native son. Though his work is in a number of Northwest institutions, including the Henry and Tacoma Art Museum, it also shows up in less-established venues, such as his old high school, where he created a 16-foot mural of Golden Gardens Park for the hallway west of the library. The Kirkland show exhibits an astounding range of styles that reference the Northwest’s best-known artists, but ultimately reveals Reno’s particular vision: His writhing marks suggest half-submerged animal and human forms, and the people and places of the Puget Sound radiate with intensity and pulsing color.