Greenwich Village folksinger Karen Dalton was uncomfortable performing, uncomfortable in the studio, and heavy into drugs. But when the needle strikes vinyl on her 1971 album, In My Own Time, and her voice rings out like a January cold front, it’s impossible not to wonder: “Why wasn’t she huge?”

For Matt Sullivan, owner of Seattle label Light in the Attic Records, his interest in reissuing In My Own Time was piqued when he ran across her name in association with Bob Dylan.

“I was reading this book on him,” says Sullivan. “And at one point when he’s talking about New York City in the ’60s, Dylan cites [Dalton] as one of his influences. So I had to find out who she was. But it’s just so hard to find out any info about her.”

Yet Sullivan managed to find a friend with a copy of In My Own Time, and upon hearing the first few notes of Dalton covering Dino Valenti’s “Something on Your Mind,” the record took hold of him and wouldn’t let go. It wasn’t folk, it wasn’t blues, it wasn’t country, and it wasn’t soul; but rather an amorphous blend akin to The Band’s early work. The songs that followed were some of the most heartbreakingly beautiful numbers Sullivan had ever heard. He was determined to let the masses hear Dalton’s voice.

While labels such as Koch, Sundazed, and even Sub Pop had been planning to reissue In My Own Time for years, Sullivan ultimately proved triumphant by badgering the hell out of Woodstock promoter Michael Lang, who owned the rights to the record.

“I originally started trying to reissue this three or four years ago,” says Sullivan. “It was just constant calls and e-mails. But I showed Michael some of the other reissues we did, like [the soul-funk compilation] Jamaica to Toronto, and I think he saw that we were going to do something really special with this.”

For a guy who played bass on Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” and in Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew sessions, In My Own Time producer Harvey Brooks speaks of Dalton as if her talent transcended that of her iconic peers.

“She was extremely soulful,” says Brooks. “Billie Holiday comes to mind, just the way she phrased things. She had a voice that was so strong you felt the microphone crackle when she got near it.

“My first thought was ‘Wow,'” he adds. “Nobody sings like that.”

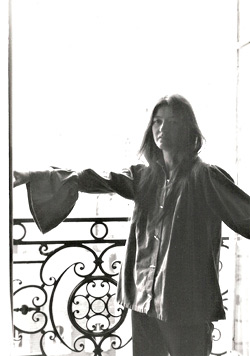

Brooks met Dalton in 1970, and by that time she had been on the Village coffeehouse scene for close to 10 years (a famous 1961 photo shows Dalton and Fred Neil singing with a chubby-cheeked Bob Dylan). As a half-Irish, half-Cherokee girl with regal dark hair and a 27-fret banjo, the Enid, Okla., native was considered one of the hippest chicks around.

“I thought she was the greatest,” says Richard Tucker, her singing partner and husband from 1960 to 1965. “I fell in love with her in 10 seconds. She had that strange paradox of having the biggest ego, but not having enough ego. She thought she was the best, but she couldn’t back it up in a consistent manner.”

Tucker says part of what kept her from fame was the fact that she was not a great recording artist and was only good live some of the time. But those nights she was on, Dalton was one of the most intense performers around, essentially convincing tragic folkie Tim Hardin that music was a worthwhile career path. “Tim always said he pursued music because of us,” says Tucker.

Tucker and Dalton functioned reasonably well together as a folk duo, but their marriage was a terrible one, he says. He never saw Dalton again after 1965, and was well aware of her addictions to heroin, speed, and alcohol. Through the years, he heard of her slow unraveling, something Brooks had to grapple with when he was hired to produce In My Own Time at Bearsville Studios in upstate New York.

“[Bearsville] was a comfortable place for her,” says Brooks of the rural studio. “And being away from the city, it’s a little harder to let the bad influences come in, and by that I mean people. She had some drug problems, so I had to keep it all in focus, and it took a little coaxing to keep her on the path. Drugs were not part of the album, but they were a part of life back then.

“It takes cognizance to make these things happen,” he adds. “You don’t get great performances in a drunken haze. I was a pretty heavy reefer smoker at the time, and even I had to put that on the shelf somewhat for this record.”

On the record, Dalton covers Richard Manuel’s “In a Station” and the haunting traditional ballad “Katie Cruel,” and turns in a sublime, weary cover of ex-husband Tucker’s “Are You Leaving for the Country.” She even makes listenable the overexposed soul numbers “When a Man Loves a Woman” and “How Sweet It Is.” The record has plenty in common with the Americana melting pot of The Band, who were wildly popular at the time. But ultimately, In My Own Time was loved by a select few and heard by almost no one else.

Brooks saw Dalton off and on through the ’70s, and watched her spiral downward amidst personal problems and addiction. They talked about doing another record, but it never came to pass. Dalton gradually drifted away from the scene entirely as her addictions grew stronger.

“She was living in uptown Manhattan, and my friend Danny Hankin was working with her,” recalls Tucker. “She’d perform every now and then, but mostly a gig would come up and Karen wouldn’t even get out of bed. She was like Billie Holiday in that way. But Billie Holiday had strength—she would punch out men. Karen was not a strong person.”

By all accounts, Dalton spent most of her final years on the streets of New York, destitute and homeless, and is believed to have died in 1993.

For the In My Own Time reissue (available Nov. 7), Light in the Attic has rolled out the red carpet, complete with superb remastering, rustic packaging, and a 30-page booklet of rare photos and liner notes by Lenny Kaye, Nick Cave, and Devendra Banhart. But what’s interesting is that no matter how much information on Dalton is revealed in the liner notes, there remains a sense of mystery surrounding her life and death.

“The more we started finding out about her, the less we could pin down,” says Sullivan. “Even the people who knew her, they don’t have any concrete details. We found out she had two children, but we couldn’t track them down at all.”

However, all that matters is all we have left: her songs and her voice.

“I’m just thrilled that this [record] is seeing the light of day,” says Brooks. “It was just one of those kinds of projects that was a labor of love, and a lot of times labors of love get lost.”