Recently, after a light meal at a lady friend’s accompanied by a bottle of wine (for the two of us), I decided to drop by some Capitol Hill bars. At the first establishment I dropped into, I remember pausing near the entrance to look up at a video screen. Next thing I know, I’m being interrogated by a number of hunky firefighters. Was I conscious? Did I remember my name? Had I recently partaken of amyl nitrate or Viagra? A plastic stretcher was deftly inserted beneath me, and the next thing I remember is the ceiling of the Swedish Hospital emergency room rolling by.

My doctor quickly determined my blood pressure to be catastrophically low, that I was anemic, and that my fainting had been caused by extensive internal bleeding, probably over several days. If I left, he said, I might die.

Such advice, coming from a peremptory man in green scrubs, is hard to ignore. So I allowed myself to be rolled upstairs to a private room in intensive care, where saline drips were attached to me and a tab of Demerol was proffered. The next morning, another doctor appeared and proposed an immediate endoscopy to find the source of my blood loss. A few hours and another Demerol later, he returned to tell me that he’d found no bleeding in my stomach—but if I’d drop by his office in a few days, he’d slip another mini-cam up my other end and attempt to track it down there.

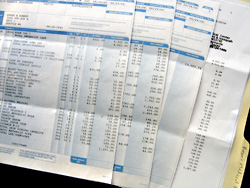

By this time, I was feeling considerably better, and insisted on being discharged from the hospital. After a stiff tussle, I was allowed to leave. For days, I continued to feel in peak condition—until the bills began coming in. The total pre-insurance tab: $17,214.74—which comes to about $956.37 per hour. So I asked the hospital to provide a detailed accounting of my treatment. The stack of papers I received made for interesting, if sometimes disturbing, reading.

The first thing I learned was that I had not fainted but suffered from “TLC”—physician-speak for “temporary loss of consciousness.” My blood pressure on arrival was 90/50, which is very low. On the other hand, my heart rate sat at a relatively normal 80 and my breathing rate a similarly placid 14. More disturbing was the blood they claimed to have found in my stool.

Everything else that happened that evening depended on that blood. Due to its alleged seriousness, by the time I left the ER, the meter stood at $2,669 (including $426 for installing the saline drip). The ER doctor also sent me to intensive care ($4,500 per day) instead of an ordinary room ($1,600). I’ll be interested to see what accounts for the $2,900 difference, since the ICU services, apart from topping off the already installed drip, consisted of attaching a clip to one of my index fingers to monitor my blood oxygen saturation.

The rest of the bill? Lab tests ran around $2,650. The squint into my stomach cost $1,702—reasonable, I guess, though $436 for the little single-use dingus that scraped up some tissue and found nothing wrong seems a little steep. The later colonoscopy that showed no bleeding was billed at $1,820. Everything else was, by comparison, chump change, down to the $44 for a “nutrition consult–IP” that I never had.

Trouble is, the whole business was based on evidence of blood in my stool—and nobody had taken a stool sample from me (it’s the kind of procedure you don’t forget). Bottom line, I fainted—maybe from the heat, maybe for some other reason. On that basis, and because my blood pressure was low, I was given full-bore ICU treatment for, it turns out, no earthly medical reason.

Had an auto mechanic made a similar call leading to similar unjustified expense, he would not see a lot of cars passing through his garage portals once word got round. Doctors are different. They need not concern themselves with the cost of the measures they recommend. Indeed, most of them are proud of the fact that they don’t know how much a Q-Tip costs, let alone a “disposable BX sterile forceps.” And their expertise goes largely unchallenged.

The patient, meanwhile, doesn’t have an advocate by his side as a litigant has in court. And as long as physicians, hospitals, and insurance companies continue to play their intricate game of absurdly high charges tempered by equally absurd write-offs for each enigmatic item, the patient will never have the slightest idea what he’s paying for, let alone whether he’s gotten his money’s worth or whether he should have had the procedure in the first place.

As I was leaving the hospital, the doctor who was signing my hall pass remarked shyly, “If you ever find out what actually happened, let me know.” I’d love to, Doc. But so far, I’m as in the dark as you are.