Two evenings with Bill Rieflin and Peter Buck: Last week at the Tractor, the two full-time members of R.E.M. powered the Minus 5, fronted by former Young Fresh Fellow Scott McCaughey, through a set of non sequitur originals and garage-rock classics. The energy level was a notch or two below a furniture-breaking party, but it was probably the best frat-rock being played anywhere in Seattle that night.

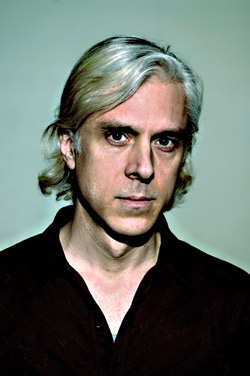

This past October, the pair joined to create a much different sound when Rieflin’s Slow Music sextet played three sets at the Crocodile. Rieflin, a veteran of the Telepaths and the Blackouts, not to mention industrial rockers Ministry, gave up his seat behind the drum kit to Matt Chamberlain to explore echoing piano chords and synthesizer textures, while Buck’s folky clangor gave way to something more subtle, and King Crimson/Bowie vet Robert Fripp added “triggered sounds” to his trademark guitar whir. The sense of open space in the music recalled—without sounding like—’70s Miles Davis, or the long, inexorable build of an Art Ensemble of Chicago performance.

Slow Music grew from Rieflin’s idea of playing “with that ambient style, those textured sort of sounds. That music seems to be made in the world of programmers, and I wanted to translate it to the world of players and performers.” The genesis was a composition built with “an old synthesizer, manipulating the sound and tinkering with it, and I kept wanting to slow it down. But it’s based in the idea of using sound to stop time and open space. That’s a contradictory idea, because music can only happen in time.”

He recalled a 1989 Swans gig: “There was one point when it was as if time stopped and sound opened up. I guess to put it in a more poetic way, you could say the silence behind the sound revealed itself, and they blended. It’s a very subjective thing, but I was with three other people, and afterward we were talking about the show, and each of these people had a similar moment. So I think it can be done objectively as well as subjectively. So Slow Music is very experimental in a way—asking, ‘How do you do that?’ It’s subjective according to each person in the group. What makes it work is staying alert, paying attention, and knowing when to join in.”

Though the band is organized around improvisation, Rieflin notes that there are some ground rules. He might name keys or throw out a “very general” adjective to guide a piece.

“I tell these musicians, when you don’t know what to play, don’t play. In our music, space is a tool to be used. It is wide open within a certain context. If someone is moved to go in a certain direction, then so be it.”

Finally, how does Rieflin deal with rock-crowd expectations when Slow Music is the sort of music often heard at the likes of the artier On the Boards?

“Slow Music,” he says, “builds up a certain electricity onstage, and that communicates to the audience. Even though the music isn’t normally what you think of as exciting, it is exciting. It’s loud.”

As for the group’s lone previous gig, “I thought the audience was fantastic. Rock clubs afford a thing that On the Boards can’t and vice versa. With this kind of music, people probably wanna sit down and listen. I mean, it’s not dance music. It’s not visceral on a physical level. On the other hand, a rock club is more casual, people can’t sit down, so that it doesn’t feel like a stuffy concert or something. But in either place, this music can hopefully break down some expectations.”