ONLY LAST WEEK, Seattle saw the power and voice of immigrants in the Northwest, most of them Hispanic. Monday’s downtown march of some 15,000 to 30,000 demonstrators (depending on who you ask), along with others around the state, certainly gives credence to estimates of 200,000-plus illegal aliens living in Washington state. (Of course, that’s a loaded term. The “illegal aliens” who’d be criminalized and/or deported under pending and controversial congressional legislation, by no means guaranteed to pass or be signed by the president, are “undocumented workers” to marchers and opponents of the bill.) If you haven’t recently hired cash workers to mow your lawn, till your fields, paint your house, tend your cattle, pick your apples, or perhaps care for your young children or aged parents, the logical question is: Who are all those people? And where did they come from? Enrique’s Journey (Random House, $26.95), Sonia Nazario’s book-length adaptation of her Pulitzer Prize–winning 2002 Los Angeles Times series, powerfully supplies the answers.

Though this is definitely a nonfiction narrative, reconstructed from Nazario’s reporting and retracing some of her young protagonist’s path, this crucially important book is like The Grapes of Wrath in Spanish. Its long subtitle, “The story of a boy’s dangerous odyssey to reunite with his mother,” really isn’t long enough. Nazario begins her tale in impoverished Honduras, omitting surnames to protect the identities of her principal figures. Made a mother too young, Lourdes is basically raising her two children alone. “She’s never been able to buy them a toy or a birthday cake,” Nazario writes. “[She] scrubs other people’s laundry in a muddy river.” Dividing her two kids among family members, 24-year-old Lourdes decides to improve her prospects in the U.S. in 1989, when Enrique is 5.

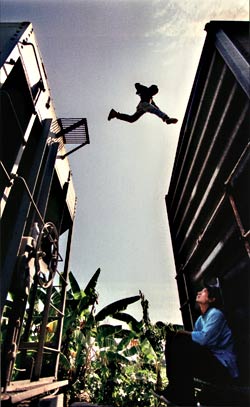

Eleven years later, desperately missing Lourdes, and somewhat socially maladjusted, he sets out to find her—hoping to become one of an estimated 48,000 children who illegally cross the U.S. border each year in search of their parents. (Some are as young as 7, Nazario reports.) Enrique starts out by foot and bus, trying to avoid Honduran and Guatemalan authorities. He and other migrants seek the railroad, dubbed “El Tren de la Muerte” (the train of death), in Mexico’s southernmost state of Chiapas—also the most dangerous region of his trek.

RIDING THE rails through Chiapas means evading both the federal police (la migra), who are notoriously corrupt and brutal, and the gangs who specifically target migrants with even more brutality. Rape, robbery, and kidnapping are commonplace; those traveling with only a U.S. phone number on a scrap of paper—their only link to family up north—can have it stolen or used for telephone extortion schemes. Migrants routinely lose limbs and lives while trying to board the trains; branches also knock them off the freight cars—as almost happened to Nazario when she traversed the same route.

She writes, “Sometimes, a madrina [man with machete] rides the train and pretends to be a migrant. The madrina radios ahead to report how many migrants are aboard.” It’s a perfect system: the madrina robs you, and la migra send you back to Honduras. En route, 5-foot-tall Enrique gets busted and detained a few times, is robbed repeatedly, and runs afoul of gangsters who knock out several teeth. (Later, he’ll use the folk remedy of gargling with urine to dull the pain.)

Nazario makes Chiapas sound horrifying, especially compared to the friendlier northern Mexico states, where peasants toss food to those on the train. Why such hostility to Central Americans? She doesn’t really delve into the macroeconomics of the situation (nor explain why Honduras is so poor). There is, however, an ugly echo of our own border dynamic—those living closest to it are often the most opposed to those trying to cross from the south. It’s “they’re taking our jobs” in a different language.

Nazario met Enrique in 2000 at a church shelter in Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, with Texas in view just over the Rio Grande. It is here that Enrique also gets stalled for a long period, waiting for that critical shot—partly dictated by luck, partly by the $1,200 his mother wires to a coyote—to cross the river. Here, Enrique is named “El Hongo” (the mushroom) for so patiently saving his pesos—earned washing cars—and studying which coyote he can trust and which he can’t (i.e., the many drunks and drug addicts). The former Honduran glue-sniffer incrementally moves closer to being a man (he’s left a pregnant girlfriend back home), closer to the U.S., closer to his mother.

I’ll leave you in suspense—so much as the subtitle permits—about the crossing and what follows. (An HBO miniseries is in the works.) Nazario’s reporting in the U.S. bears comparison to Barbara Ehrenreich’s Nickel and Dimed—how to stretch the groceries, how to share the rent—along with citing some eye-opening economic statistics. Illegals in the U.S. annually send $30 billion home to Latin America. They also contribute somewhere between $1 billion and $10 billion in goods and services here. Yet at the same time, according to a Harvard study, this pool of cheap, undocumented labor decreases wages by around 7 percent for American workers with no high-school diploma. Black Americans in this subgroup are thought to be the most adversely affected by illegal immigration.

A child of immigrants from Argentina, Nazario remains neutral, too much the reporter on these big-picture benefits and costs. California’s schools and health care system have been overwhelmed since the ’80s surge in illegal immigration—hence Proposition 187 and the new push, led by conservative Republicans, against such immigrants. One of Nazario’s chapter headings, “Schizophrenic Policies,” sums up the current national mood. A 1980 RAND study concluded the benefits exceeded social costs; then it reversed its conclusion in 1997.

Nazario alternates her narrative of Enrique’s progress with that of his girlfriend (and later, baby) back in Tegucigalpa. She asks one family member what it would take to slow emigration to El Norte, how future Enriques could remain home with families intact. “There would have to be jobs,” she’s told. “Jobs that pay okay. That’s all.”

But, as with the global economic imbalances that drive Africans to Europe, and impel Chinese peasants to Seattle, the gulf that drives Enrique’s story is only likely to widen. Though Nazario makes no predictions, one can only conclude that his incredible journey is but one of many more to follow—no matter what laws we pass, no matter how many fences we build.