It’s one thing to buy a black light and some nag champa from Hot Topic, and quite another to grab an organ and guitars, find some knee-high brown boots, and sing your own hallucination. Luckily for dudes still waiting on the chest hair, Austin sextet Black Angels fit the second category better than a pair of eggplant corduroys. Named after the Velvet Underground’s “Black Angel’s Death Song,” a cheerful little thing about fate and Armageddon, the Angels released Passover, their first full-length album, on April 11. Their label, Seattle’s Light in the Attic, is hyping it as “Native American Drone ‘n’ Roll.” We’re not sure what that means; then again, we used to shop at Hot Topic.

Either way, Passover lives up to the urgent “Wake up!” chorus of “The Sniper at the Gates of Heaven,” its third track. The opening song, “Young Men Dead,” starts with a metronomic bass line, then bursts wide with tambourine, electronic drone machine, echoing floor tom, and frontman Alex Maas’ call: “Fire for the hills, pick up your feet, let’s go.” This isn’t so much a battle cry as a sudden plunge, something like a Tilt-a-Whirl coming to a stop while you’re still spinning.

Such disequilibrium is intensified in the Angels’ live performances, where they play awash in old film clips. Warhol used polka dots and colored lights, but Black Angels projectionist Richard Whymark splices zombie flicks and talking heads. His girlfriend, Jennifer Raines, plays the organ and the drone machine. She’d been a music fan since age 8, when her mother gave her a copy of the Doors’ L.A. Woman, but had never played an instrument until two years ago. “[Maas] came up to me and asked if I wanted to learn keyboards for a show that weekend.” Was she nervous? “No. I loved it.”

Maas and lead guitarist Christian Bland went to high school in a small Texas town where Maas was scolded for singing “Walk on the Wild Side” on a street corner. Bland is a preacher’s son who has yet to convince his dad that the band is not “a waste of time.” (Maybe they should have named themselves the White Stripes instead.) Drummer Stephanie Bailey had better luck with her parents. “My family has always been really supportive,” she says. “But I had to get a degree first.” While working on her English degree from the University of Texas, Bailey spent four years drumming inside bathrooms and coat closets. “There just wasn’t enough space,” she explains. “I’d put down some towels, and drum on the floor.”

It’s true that the Black Angels wear their heroes on their sleeves—and on their instruments, in the case of Velvet Underground singer Nico, who graces Bailey’s drum kit. The Angels celebrate ’60s noir, the hazy, daisyless part of the decade, more ‘Nam than Aquarius. The mood manifests itself in Passover‘s black-and-white packaging and its songs about death, bloodhounds, and compulsive addiction. Not to mention the band’s favorite live covers, “I’m Waiting for the Man” and “All Tomorrow’s Parties.”

This reads like a cliché, especially because the chromatic “Manipulation” is basically a “Femme Fatale”/”She’s a Rainbow” mash-up, albeit with a sweeter-than-Jesus solo. However, the Angels’ most revealing idol is the late, scotch-swigging rock critic Lester Bangs, possibly the only man who loved Lou Reed even more than Alex Maas does. But as Bangs wrote, “[T]he only reason to build up an idol is to tear it down again. . . . A hero is a goddamn stupid thing to have in the first place, and a general block to anything you might wanta accomplish on your own.”

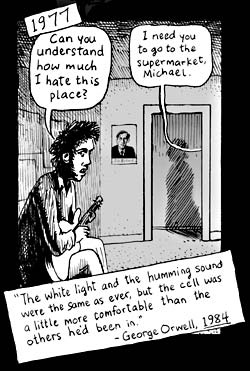

This is the Black Angels’ dilemma. Like Janis Joplin and Leonard Cohen in the Chelsea Hotel, first they loved, and now they’re leaving. At the end of Passover, there is a hidden, untitled track that plays on a previous one, “The First Vietnam War.” The bonus track’s lyrics are written as a series of letters from a soldier in Iraq: “Don’t worry about me, and tell Lindsay that I love her.” The idea is plain enough—we’ve been here before. It’s the first time on the album that the Angels try to drag the late ’60s toward today. For all their skill in re-creating a bygone era, the question is whether they can find a way to make it new.