Almost a year ago, after five years of on-again, off-again, rancorous negotiation and litigation, the Pong family, Bellevue-based hotel developers, agreed to sell a beautifully located piece of South Lake Union real estate to the city of Seattle for almost $3.9 million. At one time, the city had threatened to take the property by eminent domain, according to the Pongs, which is why they decided to sell at a price they could negotiate.

Now, though, Mayor Greg Nickels and the Seattle City Council have decided the city doesn’t need the property it once wanted so badly. On March 27, the council voted unanimously to put the property into the hands of Vulcan, billionaire Paul Allen’s holding company, which owns property that adjoins the former Pong property and had sought to buy it from them before the city started talking about eminent domain. Paul Pong, who works for his family’s business, is furious. “Vulcan used the city to kick us out because we wouldn’t sell to them,” says Pong. “When the government tries to condemn you, how do you stop it?” The mayor’s staff says there was no collusion with Vulcan against the Pongs. Moreover, officials say, the city had abandoned plans to take the property when the Pongs initiated a second round of negotiations that resulted in a sale. Vulcan has no comment. City Council President Nick Licata finds the city’s behavior troubling, but not illegal or unethical.

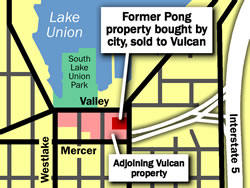

The property in question is two parcels on the corner of Fairview Avenue North and Valley Street in the South Lake Union neighborhood, where the world’s sixth-richest man and Nickels are working to create a wonderland of development that includes biotech laboratories, hotels, fancy condos, and a $22 million to $28 million makeover of 12-acre South Lake Union Park.

The Pongs bought the property for around $1.4 million in 1997. Since the neighborhood was not ready for large-scale development, they rented the building. In 1999, the Pongs assert in court documents, Vulcan approached the family and offered $3.6 million for the site. “We rejected it,” says Paul Pong.

In 2000, the city told the Pongs that it wanted the property for the Fairview/Valley Realignment Project, a transportation plan of then-Mayor Paul Schell. The city wanted to make traffic off the Mercer Street exit of Interstate 5 flow more smoothly westbound through South Lake Union. That route now involves a weave—two sharp turns to get onto Valley. If the family wouldn’t sell, the city would take the property using eminent domain, according to the court documents. The Pongs and the city began a long, drawn-out battle over the property.

Meanwhile, in 2001, to encourage development on the three blocks of Valley Street across from the new park, including the Pongs’ property, the city changed zoning to allow buildings as high as 65 feet. That same year, Schell arranged the sale to Vulcan of eight city properties, intended in the early 1970s for a freeway to the waterfront that never came to be, for $20.1 million. Several of the properties adjoined the Pongs’ parcels in the three-block section of Valley across from the park. The city’s actions provoked two feelings in the Pongs: They were excited by the apparent increased value of their property, but they worried about the encroachment of Vulcan.

The Pongs’ lawyer then was Phil Talmadge, a former state Supreme Court justice and state senator. While representing the Pongs, Talmadge discovered that the legislation that authorized the sale of the freeway properties said that any remnants from the Fairview/Valley realignment were to be sold to Vulcan at $114.67 per square foot. Some of the property in question belonged, at the time, to the Pongs. “It was the goddamnedest thing I’ve ever seen,” says Talmadge. “It purported to sell the remnants of the eminent domain, but they hadn’t done the eminent domain yet. I didn’t know a city could sell something it didn’t own.” The Pongs’ fear that the city and Vulcan were colluding increased. Mayoral staffer Mike Mann, deputy director of the Office of Management and Planning, who did not work for the city at the time, says the city was simply trying to protect the public interest. “We wanted to make sure that we weren’t stuck with unvaluable property.”

Around that time, Paul Pong visited an architect’s office in South Lake Union. He saw a model for a large, three-block development along Valley that included his family’s property. The developer was Vulcan. Throughout the ordinance authorizing the sale of the freeway property, the city referred to the potential of a three-block development along Valley Street by Vulcan, even though the developer did not, and does not now, own all of that property.

When Mayor Greg Nickels took office in 2002, transportation plans in the South Lake Union area changed. Schell’s modest idea of a Fairview Avenue North–Mercer Street realignment was replaced with the $75 million, Vulcan-backed “Two-Way Mercer Corridor Project,” which would widen Mercer, narrow Valley, and make both two-way. By January 2003, the city says, it abandoned the effort to take the Pongs’ property, except for some frontage that it needed for the corridor plan. In court documents, the Pongs say the city did not disclose that the properties would not be needed under alternative projects under consideration. The city itself asserts in court documents filed in 2004, “There are now two options, the initial plan to change the intersection angle of Fairview/Valley and a widened, two-way Mercer Street.”

On Sept. 23, 2003, the Pongs’ new lawyer, H. Peter Sorg Jr. of Lane Powell Spears Lubersky, wrote the city indicating that the Pongs were willing to sell their property for $3.5 million. The city accepted the offer and now explains it wanted to use the property as a construction staging area for the corridor project, although there is no mention of that in court documents. The Pongs, however, backed out of the deal. The next month, the city sued the Pongs, saying the family should be legally compelled to sell for the price it had named. Another round of acrimonious negotiations ensued.

In the summer of 2004, the mayor’s office directed Shiels Obletz Johnsen’s Ken Johnsen, a consultant working on the proposed 1.3-mile, $50 million South Lake Union streetcar, to find a location for the trolley’s maintenance barn. Johnsen suggested the Pongs’ property and an adjacent parcel. Those three parcels became the preferred site for the maintenance barn, although it is never mentioned in court records and the Pongs were evidently never informed of the plan.

On April 22, 2005, the city and the Pongs settled on $3,875,000 for the properties.

The next month, the South Lake Union Friends and Neighbors Community Council (SLUFAN)—an organization that enthusiastically backs development plans for the neighborhood and has a Vulcan representative and former Seattle City Council legislative aide Phil Fuji on its board—wrote the city that the preferred site of the maintenance barn was a poor location. SLUFAN wrote, “We believe that the selected site at the important Fairview and Valley intersection, while functional, may be a shortsighted solution. There is a strong feeling that this site has much greater long term potential for the City and the neighborhood. . . . ” SLUFAN’s Chris Tucker, an employee of Shurgard, which has a self-storage facility across Fairview from the Pongs’ property, says Vulcan did not initiate the suggestion.

Last summer, Vulcan did, however, call the city and suggest a property swap. The city would get property at Fairview Avenue North and Harrison Street that is better suited for a streetcar maintenance barn, and Vulcan would get three parcels of waterfront at Fairview and Valley— including the former Pong property. As part of the agreement approved last week, Vulcan will pay the city $1.8 million in cash, most of which will be needed to lay additional streetcar track to the maintenance barn location, and agreed to give the city the frontage that it needs for the Mercer Corridor project. In exchange, Vulcan gets to take control of all but three parcels in the three blocks along Valley Street across from the park, including the former Pong property.

Licata says, “The question is whether Vulcan used the city through timing and opportunity, or was there collusion?”

Pong believes it’s very clear what happened. “The city intervened and helped out a large developer,” he says. “They forced us out in an unjustified way.” Mayoral staffer Mann says, “The city has made a series of transportation decisions that have benefited the city at each step of the way.” Licata says he is unhappy about the outcome of the city’s actions. “It raises serious doubts in my mind about whether this is the morally right thing to do, even if it is legal.”