Close relationships strained to the breaking point against the backdrop of a modern West: Book-It’s Plainsong (through Sunday, March 5; Book-It Theater, 206-216-0833, www.book-it.org) bears only a passing resemblance to Brokeback Mountain, yet I hope the movie inspires people, in a roundabout way, to see the play, a less tragic but no less heartfelt piece about how families uncouple and recouple, like trains at a switching yard.

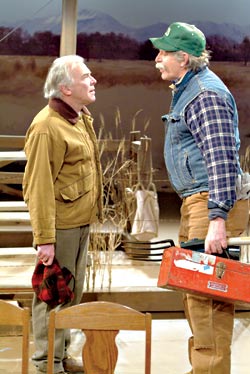

Kevin McKeon, who adapted Kent Haruf’s 1999 novel (a National Book Award finalist), stars as Tom Guthrie, a brooding schoolteacher in rural Colorado stuck between two women, his depressed wife and an interested fellow teacher, Maggie (Annie Lareau). His problems don’t end there—he’s also got a bully of a student to deal with and two precocious preteen boys to raise. Just outside Tom’s frame of vision, a pregnant high-school girl, Victoria (Joy Anuhea Medeiros), bounces from home to home until two aging bachelor brothers, the McPherons (Wesley Rice and Clark Sandford), reluctantly take her in.

In the wrong hands, this material could have ended up treacly as hell, but director Myra Platt gets straightforward performances from her extremely strong cast. (There’s some particularly deft double casting; most impressive is Marissa Price, bringing languid sadness to Tom’s wife, Ella, then turning vicious as the mother of one of his students.) Platt also gets a lot of mileage out of Bill Forrester’s smart set. A movable fence, a couple of barn doors, and a painted backdrop evoke a Colorado of the mind—but once the show’s vivid characters start living, working, and wooing in and around them, the setting begins to seem very real.

The story’s various plotlines emerge in vignettes, then gradually intertwine; most moving is the tentative relationship between the McPherons and Victoria. Her need for solid parental figures is obvious, but their need for her—for someone other than themselves to take care of—emerges much more subtly. When it does, in a great scene set in a department store, Rice and Sandford avoid easy sentimentality. (Medeiros, superb at depicting Victoria’s fluctuation between strength and vulnerability throughout the show, is also excellent here.) The quiet, unemotional man (the “strong silent type”) is a Western cliché, but these two actors imbue the brothers with a specific, believable will to break the silence and lead lives more connected to their community.