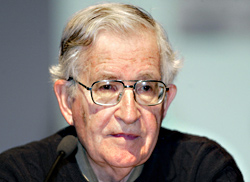

For more than 40 years, MIT professor Noam Chomsky has been one of the world’s leading intellectual critics of U.S. foreign policy. Chomsky, who turned 77 last month, vows not to slow down “as long as I’m ambulatory.” I admire and respect Chomsky, but I’ve never been that much of a fan of his writing. His conclusions are invariably well documented, but they carry a certain snide “well, of course I’m right” tone that wears thin fast. I suspect it’s also alienating to people not predisposed to agree with him.

Nonetheless, Chomsky’s achievements as a political analyst are truly remarkable. And he still has a lot to say, invariably focusing on the longer term, the big picture. Last month, I interviewed him twice by phone from his office in Cambridge, Mass. He spent lots of time on the morass in Iraq and the War on Terror. I asked how the U.S. could measure victory in an antiterror “war” set up as an open-ended crusade against a tactic.

“There are metrics,” Chomsky replied. “For example, you can measure the number of terrorist attacks. Well, that’s gone up sharply under the Bush administration, very sharply after the Iraq war . . . it increased terror. In fact, it even created something which never existed—new training ground for terrorists, much more sophisticated than Afghanistan. . . . There is no War on Terror. It’s a minor consideration. So invading Iraq and taking control of the world’s energy resources was way more important than the threat of terror.”

In general, Chomsky said, the Bush administration isn’t terribly concerned with that or other ramifications of U.S. foreign policy. “They don’t care that much,” he said. “Same with global warming. They’re not stupid. They know that they’re increasing the threat of a serious catastrophe. But that’s a generation or two away. Who cares? There’s basically two principles that define the Bush administration policies: stuff the pockets of your rich friends with dollars and increase your control over the world. Almost everything follows from that. If you happen to blow up the world, well, you know, it’s somebody else’s business. Stuff happens, as Rumsfeld said.”

I asked Chomsky what he thought the U.S. should do in Iraq.

“We are under a rigid doctrine in the West, a religious fanaticism, that says we must believe that the United States would have invaded Iraq even if its main product was lettuce and pickles, and the oil resources of the world were in Central Africa. . . . If you have three gray cells functioning, you know that that’s perfect nonsense. The U.S. invaded Iraq because it has enormous oil resources, mostly untapped, and it’s right in the heart of the world’s energy system. . . .

“Take any day’s newspapers or journals and so on. They start by saying the United States aims to bring about a sovereign democratic independent Iraq. I mean, is that even a remote possibility? . . . If it’s more or less democratic, it’ll have a Shiite majority. . . . So you get an Iraqi/Iran loose alliance. Furthermore, right across the border in Saudi Arabia, there’s a Shiite population which has been bitterly oppressed by the U.S.-backed fundamentalist tyranny. . . . That happens to be where most of Saudi Arabian oil is. OK, so you can just imagine the ultimate nightmare in Washington: a loose Shiite alliance controlling most of the world’s oil, independent of Washington and probably turning toward the East, where China and others are eager to make relationships with them, and are already doing it.”

While that sounds like incompetence, there’s another explanation. “We’re not allowed to concede that our leaders have rational imperial interests,” Chomsky said. “We have to assume that they’re good-hearted and bumbling. But they’re not. They’re perfectly sensible. . . . Yes, I think there should be withdrawal, but we have to talk about it in the real world and know what the White House is thinking.”

I asked about Chinese resource consumption and what it means for the future relationship of the U.S. and China. He essentially shrugged.

“If you believe in markets, the way we’re supposed to, compete for resources through the market. So what’s the problem? The problem is that the United States doesn’t like the way it’s coming out. Well, too bad. Who has ever liked the way it’s coming out when you’re not winning? China isn’t any kind of threat. We can make it a threat. If you increase the military threats against China, then they will respond. And they’re already doing it. They’ll respond by building up their military forces, their offensive military capacity, and that’s a threat. So, yeah, we can force them to become a threat.”

There was more—much more (Full interview). But on balance, despite all of the world’s turmoil, Chomsky is optimistic about popular opinion in America.

“It turns out that, you know, I’m pretty much in the mainstream of public opinion. . . . On most crucial issues, the ones we’ve been talking about, I find myself pretty much at the critical end, but within the spectrum of public opinion. I think that’s a very hopeful sign. I think the United States ought to be an organizer’s paradise.”