If ever you’ve breathed the competitive, hierarchical air of the corporate office, you know how easily it can happen: Some empty-souled pimp of opportunity, “scarce half made up” and thrust before his time into the adjacent cubicle, determines to “prove a villain.” Thus is born “hell’s black intelligencer,” the corporate climber. The reign of terror begins harmlessly enough, with a sugar-coated e-mail or two, some innocuous bit of interoffice gossip that sows the seeds of your downfall. Before you know it, you’re packing up your desk wondering what hit you.

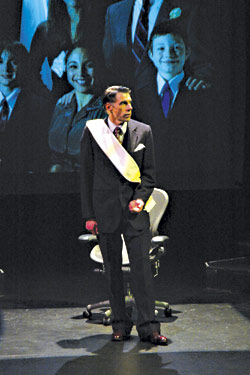

Seattle Shakespeare Company’s chamber production of Richard III (through Sunday, Jan. 29, at Center House Theatre; 206- 733-8222, www.seattleshakespeare.org), a retelling of the rogue’s dastardly rise and fall set in a modern high-tech corporation, opens onto a set as bare and cold as a snowstorm at midnight, as the audience is treated to a slick videotaped presentation outlining the historical background of the Wars of the Roses and the houses of Lancaster and York. Finally, Richard III (Todd Jefferson Moore), gaunt, limping, with an oily swoop of dark hair accenting his ashen complexion and piercing eyes, takes his place behind a lone podium. “Now is the winter of our discontent,” he states dryly before shooting off the first of many scheming e-mails: Someone named “G” will murder Edward’s heirs. A laptop, a laptop, my kingdom for a laptop.

This first scene, with its technological shock of recognition, is more comic than menacing, and sets the tone for everything that follows. This Richard, though devious and twisted to the end, is less God’s grand defiler than devilish file clerk, a cunning, smarmy player whose every calculated move reveals a heart shriveled by small lusts and self-loathing. Director Gregg Loughridge sidesteps any question of whether such corporate politicking is sufficient fodder for the depth and breadth of Elizabethan tragedy by loading the play with pop-cultural signifiers and technological baubles while downplaying the historical sweep of Shakespeare’s original. Such give-and-take is less a matter of dramatic necessity than aesthetic choice: Baz Luhrmann, for example, in his surprisingly effective adaptation of Romeo and Juliet, was able to transplant the troubles in Verona to an L.A.-style gang turf war (complete with shiny rims, gunplay, and an MDMA party) without losing any of that play’s elemental power or cosmic fatalism. Despite the havoc wrought by Richard’s machinations, it never feels like there’s much at stake here—nothing so significant as the fate of England.

Large scale or small, the spectacle itself is a pleasure to behold, thanks mostly to the acting. Moore takes the full measure of Richard’s unctuousness, discovering dark and gleefully cynical humor in every nook and cranny of his character. His reptilian seduction of Lady Anne (Alyson Bedford), a seething blend of charm and self-abasement, is almost too hideous to watch, and his oration in the final act is a biting satire of right-wing demagoguery. Lori Larsen is especially good in her primary role as the sharp-tongued Queen Margaret (she also plays Brakenbury and Lord Ely), and both Richard Ziman (as Buckingham, Clarence, and the moderator) and Connor Toms (as Rivers, Richmond, and Tyrell) turn in noteworthy performances.

Purists may be displeased with the way Loughridge forgoes the play’s more tragic elements, but it’s hard to dismiss the unity of his vision and its execution. The play is filled with clever and telling details of corrupted humanity: Richard sending Tyrell his plans for the princes’ murders via Federal Express, or the Battle of Bosworth Field played out as a town hall–style debate, with England divided into red and blue provinces. Such well-integrated flourishes shift the play’s perspective in the direction of gallows humor. Without pushing too hard, Loughridge draws lacerating satire from Shakespeare’s text. If this Richard III lacks swordplay, at least the language still cuts.