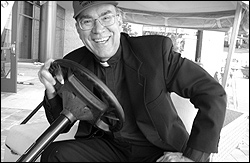

A lawyer is deposing a potential witness in the case of a woman who alleges that in the 1970s, when a child, she was abused and impregnated by a Jesuit priest in Alaska. The lawyer represents her, and the man he is questioning, in preparation for trial, is a key figure who later served as the priest’s supervisor. Key and prominent. Father Stephen Sundborg today is president of Seattle University.

Sundborg has just said that he can’t talk about conversations he had with Father James Poole about sexual behavior because they were confidential communication between a priest and his supervisor, called “manifestation of conscience.” At the time of those conversations with Poole in the early to mid-1990s, Sundborg was head of a regional Jesuit domain known as the Oregon Province.

Deposing Sundborg on Oct. 11, attorney John Manly offers a fantastical scenario to discern just how far the university president is willing to take such secrecy.

Manly: “If a priest while you were provincial, manifested to you that he had raped a seven- or eight-year-old little girl on the day of her first communion, he chopped her head off after the rape, buried her body, had sex with her body after he chopped her head off and was hiding it, and you knew that the parents and the police were looking for that child, would you alert the authorities?”

Sundborg: “There is nothing that is said that I would learn in a manifestation of conscience that I would reveal to another person.”

Manly: “So you wouldn’t tell the police in that situation.”

Sundborg: “I would not.”

The case of Jane Doe 2, as she is known in the lawsuit, raises questions about the legality and ethics of clerical secrecy, particularly in child-abuse cases. It is also a potentially explosive situation for Sundborg, given his position at the Jesuit university. Manly claims there were “complaints about misconduct with girls and women dating back to the early ’60s” involving Poole. But Jim Gorski, an attorney for the Jesuits, says the first allegation against Poole of child abuse was in late 2002 or early 2003. “I received no reports of abuse of minors by James Poole,” Sundborg wrote in a letter to the Seattle University community last week. He did acknowledge meeting with “adult victims of sexual misconduct.”

At the time of the private conversations, Poole was working as a hospital chaplain in Tacoma. In 1994, Sundborg sent him to a Catholic facility in New Mexico for treatment related to sexual transgressions, after which Poole returned to his Tacoma post.

“While I could never reveal anything said to me by a Jesuit in a manifestation of conscience,” Sundborg continued in his letter, “I could have and would have acted to guarantee that young persons were protected, if ever sexual abuse of children were mentioned.” He did not specify how he would have done so, and Sundborg could not be reached for elaboration.

Meanwhile, the Jesuits’ lawyers continue to fight in Superior Court in Alaska to prevent Sundborg and other former and present provincials from testifying about what was said to them during Poole’s manifestations of conscience. Besides Poole, the defendants in the lawsuit in Nome are the Catholic Bishop of Northern Alaska; the Society of Jesus, Oregon Province; and the Society of Jesus, Alaska. It is set for trial in February.

The appropriateness of clerical secrecy is coming under increasing scrutiny. It arose, too, in a King County Superior Court lawsuit that led to a $4.2 million jury award last month. In that case, a woman brought up in the Mormon faith, Jessica Cavalieri, said she had told church officials that her stepfather was abusing her. The officials did not report this to police, even after the stepfather began abusing Cavalieri’s sister as well, according to Cavalieri’s lawsuit. The officials claimed in the court case that what they had been told by Cavalieri and her stepfather, Peter Taylor, was privileged information, and they would not speak about it unless they received a waiver from Cavalieri and Taylor.

Jim Wellman, chair of the University of Washington’s comparative religion department and a Presbyterian minister, says confidentiality between an individual and a pastor is intended to encourage openness. “It’s giving people someplace to go and to confess where they feel safe,” Wellman says. He recognizes the thorny question that arises when an individual is confessing a crime, such as child abuse. But Christian tenets provide for such individuals, too, Wellman says. “Every person is redeemable finally and is a child of God,” and the way to redemption is through repentance. “As a clergy person, you have to be responsible to all people, not just the victim,” Wellman says. “That’s the radical nature of grace.”

But lawyers for Jane Doe 2 (Jane Doe 1 is one of two others who have settled similar but separate suits against Poole) point out that the information that the Jesuits claim is privileged was not communicated in a confession. A manifestation of conscience is something different. At least every year, the head of every Jesuit province has a meeting with the priests under him. In those meetings, priests are supposed to reveal, or “manifest,” their actions and sins. Sundborg, in his letter, explained how he saw those meetings. “As a provincial I had a sacred duty to know and guide the Jesuits under my care. Every Jesuit needed to know that he could open himself up totally to me during this required, special accounting so that he could live his vows of obedience and could trust that he was completely known by me as his provincial.”

Yet provincials also use these meetings to help determine a priest’s proper placement. Ken Roosa, an attorney representing Jane Doe 2, argues that the manifestation of conscience is essentially a job review, not a spiritual activity. “It’s no different than General Motors declaring itself a religion and saying that anything employees tell a supervisor can’t be used in a state of law,” he says. Co-counsel Manly asserts that the Jesuits are using the term “manifestation of conscience” to cover up information that they don’t want known.

In the Mormon case, too, plaintiff lawyer Timothy Kosnoff says, the clergy were trying to expand the confidentiality privilege beyond confession. He notes that Cavalieri was not confessing to Bishop Bruce Hatch when, as a young teenager, she told him about being abused since age 7. “This was a girl who went to her bishop and wanted concrete help,” he says. Attorney Tom Frey, who represented the Mormon church in the case, says that according to doctrine, when an individual meets with a bishop seeking counsel or advice, whatever transpires is confidential—a sweeping privilege that Kosnoff calls “a ridiculous extreme.”

Hatch eventually did testify about his meeting with Cavalieri after she issued a waiver. He claimed that she denied, in fact, a rumor that she was being abused. A bishop and stake president who met with her stepfather years later, after the allegation of abuse came to their attention, never testified about what was said because the stepfather refused to waive confidentiality. The court agreed that they did not have to testify.

Washington law dictates that a member of the clergy not be required to testify about any “confession” made to that clergy member in “his or her professional character.” While the word “confession” is used, some case law provides for a broad interpretation of what constitutes a confession. In Alaska, where the Poole cases are being heard, the law is even more broadly written, referring not to confession but to a “confidential communication” between an individual and a clergy member.

Other professionals who enjoy similar confidential privileges—psychotherapists and doctors, for instance—are nonetheless subject to a mandatory reporting law that requires them to break confidentiality when child abuse is involved. In Washington, the clergy used to be mandatory reporters, too. But the Legislature changed that in 1975.

Even if clergy are not legally bound to report criminal activity that is harming children, are they morally bound to? “The leader in a church is responsible to protect the children,” says Patricia Killen, chair of the religion department at Pacific Lutheran University. “Whether you protect the children by reporting to civil authorities or not, that is the point of debate.” The answer depends in part on whether you think the church can effectively handle these cases internally. Given the flood of clergy sex-abuse cases in recent years, Killen believes the public is increasingly doubtful. “We’re reaching a point in the U.S., in terms of the credibility and durability of church communities, that it’s much harder to make the argument for not reporting,” she says.