Digital cameras will be snapping across America during the holidays, and JPEGs will be duly attached to family members unable to fly in from Tulsa for the feasts. The photographic image has never been more ubiquitous; at the same time, printing advances (and cost efficiencies abroad) have made photo books more affordable than ever as gifts. And there’s a lot to choose from this year. Close to home, nature photographer Art Wolfe has extended his brand with two new titles. The paperbound, all-color Seven Summits (Sasquatch, $30) documents the seven major peaks of the Northwest and their habitats. He’s climbed them all, and the views will also appeal as a memento to any fellow alpinist. His large-format hardcover Vanishing Acts (Bulfinch, $50) reveals how animals conceal themselves through camouflage—a white grouse in the snow, snakes as thin and green as grass, bugs like twigs, and fish like coral. Several of his hard-to-find subjects are from Washington state, including the much-maligned northern spotted owl, which might truly be a vanishing act.

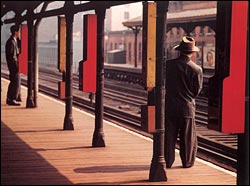

Though she never got the glamorous renown of Margaret Bourke-White or Dorothea Lange, a lenswoman receives her posthumous due in Esther Bubley: On Assignment (Aperture, $35). Bubley was very much the working photojournalist, doing magazine spreads and corporate shoots from the ’40s through the ’60s. Assignments that sound mundane—and therefore like second-class “women’s work”—she made acute and penetrating, especially when she switched from large-format cameras to the more agile 35 mm idiom. In the golden age of Life (where she also received commissions), she brought stark, street-level realism to slick pages. Shooting mental-ward patients for Ladies’ Home Journal in 1949, for example, she frames a distraught girl, hand held protectively over her face, without making her schizophrenia either naked or noble. In this way, Bubley’s a precursor to Diane Arbus and Frederick Wiseman. She rarely composed in color; a study of New York City’s Third Avenue El shows the influence of Hopper on her art.

More in the contemporary art photography vein, and also from Aperture, are David Hilliard: Photographs ($50) and America ($40) from Katy Grannan. Hilliard’s the older and more established artist; he foregrounds his gay identity through a strongly horizontal color montage that’s sometime narrative and other times purely formal. His great love for his father—scruffy, tattooed, and often bare-chested—is a repeated subject. One witty series of panels features Dad in an overwhelming supermarket cereal-box aisle, captioned, “His Problem With Plurality.” Grannan, only 36, places her subjects— recruited through newspapers—like odalisques in the leaves and dirt. You get every age and body type, some nude and some half-dressed, also posed in retro wood-paneled rec rooms or lakes—sometimes with natural backlighting suggesting an old ’70s Playboy spread. Both artistic and scholarly is Looking at Atget (Yale, $45), which displays and examines the influential pre–World War I work of Eugène Atget (1857–1927). His fondness for store window displays and mannequins appealed to the surrealists and Berenice Abbott (who collected and protected his work), yet his gorgeous, large-format silver prints have as much in common with daguerreotypes.

Jim Marshall: Jazz (Chronicle, $35) is entirely modern, a compendium of his backstage snaps of bebop greats—Monk, Coltrane, Diz, Miles—and the occasional showbiz type, too. There’s Steve McQueen absorbing Miles Davis’ aura of cool at Monterey ’63, or Sammy Davis Jr. in early ’70s glory at his makeup table. My favorite visitor is Alan Ginsberg, bald and with a bedraggled beard, staring at Thelonious Monk with all the slack-jawed awe of a teenage girl seeing the Beatles at Shea Stadium.

For pure travel porn, you can’t beat Wide Angle: National Geographic Greatest Places (National Geographic, $30), with 260 shots (most in color) arranged by continent. It’s about the size and weight of a turkey, stuffed with landscapes, animals, and ethnographic shots. It’s kitsch-free, edited for coffee-table display, and the various mountains, deserts, and snowscapes might have you surfing airfares to your next vacation spot. After the holidays, after all, January’s the perfect time for a getaway. Just don’t forget to bring your own camera.