Two King County Jail inmates died this year from suicides that could have been prevented, newly obtained records show. Internal jail records also reveal that another county inmate, after just a few days in the downtown jail last year, suddenly died from a rare flesh-eating disease. And the death of a mentally ill prisoner found with a wad of gauze stuck in his throat last year was later ruled a death by natural causes.

To some jail health workers and custody officers, these critical cases raise more questions about downtown jail operations. Staffing and medical record-keeping fall short, they say, affecting inmate care. Some jail-death investigations are self-serving, leaving a trail of lingering questions. And these jail sources worry that conditions have contributed to an increase in jail deaths. As Seattle Weekly has reported (see “Dead-End Jail,” Sept. 21), three downtown inmates died in 2000–02, while 13 died from 2003 through July of this year—despite a jail population decline. Now, county and city officials are promising changes and closer scrutiny of King County Jail operations. County Executive Ron Sims says the jail has begun a review of procedures and policies related to intake and assessment. Meantime, there’s new information about recent deaths that reinforces the need for change.

Nurses say the inmate who died from flesh-eating disease likely could not have been helped sooner. But like the two suicides this year, the 2004 death of a man named Wade Scott Brown could have been averted, they say, whether the cause was the gauze wad or not. Jail officials say that isn’t so. A shift commander who investigated the case wrote this conclusion to Brown’s half-century of life: “Staff could not have known that this incident was going to happen,” he stated in his final report. “All duties leading up to this incident were performed in accordance with the department’s policies and procedures. . . . “

Brown, a real-estate salesman, had been arrested in Shoreline for making threats during a family dispute. In jail, he exhibited mental-health problems that required special attention. He sometimes became catatonic, showered with his clothes on, talked gibberish, and burst into laughter for no apparent reason. Two days before his death, he was found lying naked on the floor of his seventh-floor psychiatric cell at the downtown Seattle jail, unresponsive. Next to him on the floor was an uneaten serving of spaghetti, a pair of wet pants, and a puddle from a leaking overhead sprinkler. There was a heavy odor of urine.

The 6-foot, 250-pound Brown was wheeled in a restraint chair to another cell. When his handcuffs were removed, he remained in the same position, as if still cuffed. According to an internal report, a nurse told custody officers that “due to his medical problems” they “should watch him closely.” Almost exactly 48 hours later, at 9 p.m. on April 6, 2004, 11 days after he was booked, Scott was found dead in his cell. He was naked but partially wrapped in a standard-issue antisuicide blanket. (Its reinforced material can’t be ripped and used as a noose.) Brown was reportedly being checked every half-hour. When found, his face and chest were a bluish purple from pooled blood, indicating postmortem lividity, though the jail’s internal report does not pinpoint time of death. County health officials say they can’t discuss medical details due to privacy laws. But a county health nurse with knowledge of the case says that if Brown had been closely watched as requested, he might have been helped earlier and sent to a hospital.

Adding to the questions was the gauze. According to the reports of two officers, nursing staff found the wad in Brown’s throat before they began revival attempts. A King County Medical Examiner’s report also notes, “Material reportedly removed from his oral cavity was collected as evidence” from the death scene. The implication is that Brown—or someone—could have intentionally shoved it down his windpipe. But it wasn’t a suicide or a homicide, the jail decided, and police could find no evidence otherwise. The direct cause of death was, officially, biventricular cardiac hypertrophy and dilation, based on the medical examiner’s findings. Wade Brown, 50, died of heart failure. “We take it personally when someone dies,” says the jail’s chief, Reed Holtgeerts, director of King County Department of Adult and Juvenile Detention. “But I don’t know what more the staff could have done.”

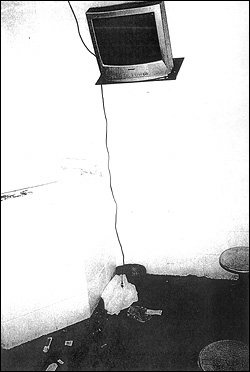

More might have been done in two other cases, now officially ruled suicides. Sabrina Owens, 36, who caused a horrific auto accident in a stolen truck, hanged herself May 11 while alone in a holding cell. Using an easily accessible, 6-foot power cord from a wall-mounted TV set, she wrapped it around her neck and then leaned forward, almost to her knees, strangling herself. Though a jail supervisor’s review found the “situation was handled correctly,” Holtgeerts now allows that, in hindsight, “It wasn’t the best thing to have those [cords] in there.” Owens had not revealed any suicidal tendencies during intake, and the holding cell she was placed in is usually occupied by two or three others, he says. “But we’re reducing [the size] of all those cords” now.

Gas-station robber Ron Hicks, 43, who had earlier attempted suicide by hoarding and ingesting pills in the jail, apparently used an identical method to kill himself July 26, the medical examiner now confirms. He died of acute intoxication of amitriphyline and bupropion, the antidepressants the jail was providing him. Three months after his demise, the jail still can’t say how he might have amassed the meds, though an investigation continues. Apparently doubting initial indicators, the jail had until recently listed his death on a statistical chart as “not” suicide. Maj. William Hayes, jail spokesperson, says the department now “has confirmed that Mr. Hicks’ death was by suicide and will be classified as such.”

The county is required by law to report any natural death, homicide, or suicide to the U.S. Justice Department, but the county has no policy to regularly announce deaths to the public. This story, for example, is the first to reveal the suicide determination in Hicks’ case. Regular accounting of jail deaths could be an important measure of how well the facility is functioning.

Also inconsistent is the jail’s death investigation procedure. According to written policy, the detention department, along with outside agencies, is to investigate all deaths “in” the jail. But there is no uniform policy to investigate the deaths of all inmates, such as those who wind up at Harborview Medical Center and later expire there. Holtgeerts says the jail leaves it up to outside agencies to do full investigations in some cases. The result is that some deaths result in thick jail investigative files, others a few pages, and some apparently no paperwork at all. Of eight inmate deaths this year and last, the jail could provide postmortem investigation records on only five. In one “file”—two pages of printed e-mails—a health department worker asked a jail commander if the hospital death of a man on electronic home detention should trigger the jail’s investigation protocol. The commander responded: “I don’t think so.” Fine, said the worker, the jail didn’t have any medical paperwork on him anyway.

Another small investigation file briefly details the unusual death of 40-year-old mechanic Patrick A. Harrington Jr. During intake on Jan. 21, 2004, the SeaTac man told an officer he was bipolar and had hepatitis. After complaining of shortness of breath at 9 a.m. on Jan. 24, while having a dressing changed on an infected left arm in a jail triage room, Harrington was taken to the infirmary and later transferred to Harborview. A report states Harrington’s prognosis was “bleak from the onset and [he] was predicted to expire soon after he was admitted to HMC.” He died at 3 the next morning, four days after he had been committed for a 20-day sentence related to an earlier theft. One day after his death, an executive duty officer cleared the jail of any responsibility, noting there was no “failure of staff to respond appropriately.” An autopsy found Harrington’s infection had apparently led to flesh-eating disease, a rare and often-fatal bacterial infection of the soft tissue. The disease, while not contagious, is usually acquired through physical contact with others and can act swiftly. (The medical examiner says a secondary death cause was chronic drug-injection abuse.) There’s no indication the jail knew of Harrington’s condition until he apparently began experiencing toxic shock. The jail did not report any complications from the incident affecting staff or other inmates. James Apa, spokesperson for the county’s health department, which runs the jail infirmary, says he’s prevented by medical privacy laws from providing details. But, “I can say, in general, the disease is not transmitted person to person.”

In recent years, inmate population at the 1,700-bed, downtown facility has steeply declined. Including inmates at the Regional Justice Center in Kent, the countywide adult jail population has dropped from 2,900 to 2,300. Corresponding staffing cuts have saved the county millions. But like the paring down of correctional-officer ranks, leading to more costly overtime, health staffers think some cuts have a negative effect. Take the elimination of a night psychiatric nurse. “That has left our psych patients basically unattended by medical staff for at least eight hours every night,” says a clinic worker, who, like others interviewed, asked not to be named. Some psych inmates, the worker says, go without medical treatment because there are only two day-shift nurses. Health spokesperson Apa says the county is “re-engineering” the psych program.

Nurses also feel their work is compromised by a lack of inmate medical histories. “We no longer use a medical chart system,” says one. “We refer everyone to the clinic based on general priority—the sickest first.” Without an organized chart system, “there are stacks of papers all over the clinic area with lab results, treatment records, and so on.” Sabrina Owens arrived at the jail wearing—for reasons unknown to jailers—a Harborview wristband, according to an internal report. When she was booked, “there was no information passed on . . . and no paperwork was with Owens.” Apa says the lack of complete med charts “can present challenges at times because we have two facilities. We have recognized it’s an issue, and that’s why [the County Council has] approved a new electronic medical records system.” It won’t be ready until 2007, however.

Sandeep Kaushik, a spokesperson for Sims, says his boss is “aware of the fact there have been deaths and suicides and is taking the issue very seriously.” Among planned changes, the jail will permanently include a health worker at the initial intake process “to better identify people who might be unstable, so they don’t slip through the cracks,” says Kaushik. County detention director Holtgeerts says the new procedure is already in use and that screening will be further improved next year with the completion of a remodeled intake area. Additionally, Seattle City Council member Tom Rasmussen, a member of the city-county health board, has requested new data on the health and mortality of King County prisoners. In his request to the health department, Rasmussen wrote, “From my reading of the [earlier] Seattle Weekly article it appears that there is inconsistency or uncertainty regarding reported deaths of King County Jail prisoners.” He is seeking inmate health statistics from the past five years and wants the department to provide an annual report on jail deaths. “I hope this is the beginning of a significant improvement,” Rasmussen said in an interview.