Noah Baumbach, the wunderkind auteur behind Kicking and Screaming (sort of a 1995 version of Garden State), seized the top writing and directing awards at Sundance this year for his wickedly, heartbreakingly funny divorce drama, The Squid and the Whale (which opens Friday, Nov. 4, at the Varsity and other theaters). It’s an exhilarating evisceration of Baumbach’s real-life father, Jonathan, a brilliant literary critic and fiction writer who taught at the UW in the 1970s and split with Baumbach’s mom, the more brilliant former Village Voice critic and fiction writer Georgia Brown, in Brooklyn’s Park Slope in the mid-1980s.

The title likens the divorcing parents to New York’s famous Museum of Natural History diorama depicting a squid and a whale locked in mortal combat. It’s ironic: Even though the combat seems pretty damn mortal to the kids caught in the middle—Walt (Jesse Eisenberg), 16, and Frank (Kevin Kline’s talented real-life son Owen), 12—the parents aren’t drawn as battling giants. It’s a one-sided fight between mother and loser. Joan (Laura Linney), the Georgia Brown character, is like a cuter version of Linney’s role in Kinsey, the affably, guiltlessly promiscuous life-affirmer, high achiever, and pillar of her family. Joan upsets the family dynamic by taking up writing in midlife and instantly selling stories to The New Yorker. Her rivalrous and downwardly mobile English professor husband, Bernard (Jeff Daniels), is singed by her skyrocket success, like the Warner Bros. Coyote turned to a disconsolate pillar of ash after his incendiary plot against the Road Runner backfires.

As a character assassin’s portrait of Baumbach senior, Daniels has never been better—and Daniels has never been anything but great. Here he walks a perilous tightrope: With every artful flicker of his wounded, wounding eyes and twitch of his nerdy beard, he conveys the fraudulence of Bernard, his thwarted ambition and scalding shame, his hypocrisy and penny-pinching, his jesuitical lucubrations to justify his ridiculous self-serving schemes. And yet he somehow keeps him this side of hatefulness. We actually sympathize with the crooked, snookering schnook. We don’t come to love him, but we quite like laughing our asses off at his ego-shattering pratfalls.

If anything is known, Bernard knows it—and lets you know you don’t, even if you know better than he does. He’s so competitive he can’t let hypersensitive Frank win at Ping-Pong. He causes the brittle, worshipful Walt (director Noah’s surrogate) to ape his risible intellectual monkeyshines. He swallows his dad’s act, hook, line, and literary allusion. Father and son go around bad-mouthing Dickens novels they’ve not yet read; Walt pretentiously proclaims the ending of The Metamorphosis to be “very Kafkaesque,” and on advice from asshole Dad, ridicules his angelic girlfriend (Halley Feiffer) right out of bed.

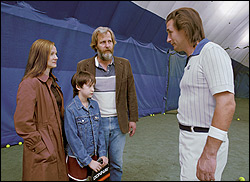

Following his parents’ split, Walt moves into his dad’s shitty new wrong-side-of-Brooklyn apartment. Perhaps influenced by the poster there for The Mother and the Whore, he later tells his mom she’s a whore for dumping Dad and dating her hunky mensch of a tennis instructor (winningly, grinningly limned by Billy Baldwin). Not that Bernard is a monk himself—he kinkily invites his slinkiest student (Anna Paquin) to move in with him and Walt.

Frank’s behavior is harder to figure. He sides with Mom, and acts out his Sturm und Drang by playing with her underwear when she’s out, sticking nuts up his nose, and wiping his sperm on lockers at school. (At Sundance, Baumbach stressed that his own brother did not do this in real life.) Though his character is more schematic than the absolutely lifelike Walt, who evinces the director’s chilly personality, Frank helps give the film a warmer tone. Bernard and Walt make funny, ugly music together; poor Frank’s victimization by Bernard perversely humanizes both.

Because it’s about hyperarticulately selfish Manhattan neurotics, the flick fetches rote comparisons with Woody Allen, but Baumbach is his own man. His style with camera and typewriter is jumpy and distinctive, smarter than Allen’s. He’s not about the quip; he’s all about character and heightened realism. Until recently, when he packed up for London, Allen habitually crafted a fantasy Manhattan; Baumbach has a New Yorker writer’s eye for urban authenticity. (Like mother, like son.)

The film’s sole weak spot, despite Linney’s characteristic genius, is the vaguely drawn mom role. She’s too simply the good guy, even though she sleeps around chronically and probably shouldn’t talk about it quite so openly with her kids. A friend of the family tells me that Baumbach simply hasn’t worked through his mom worship the way he’s overcome his dad worship (and replaced it with merciless loathing, at least on film). No matter: This amazingly bad (yet magnetically fascinating) dad is enough to make Whale a time-capsule keeper.