George Clooney has no use for Anderson Cooper getting all teary and indignant about Hurricane Katrina and our government’s failure to respond. In his tight, smart, timely, and very self-assured second feature, Good Night, and Good Luck (which opens Friday, Oct. 14, at the Guild 45 and Uptown theaters), the actor-producer-director takes us 50 years back to an era of political catastrophe, when journalists’ feelings were as buttoned-down as their shirts. Their white shirts. Clooney shot Good Night in black-and-white, on a soundstage basically reflecting the early days of television at CBS. There, star correspondent Edward R. Murrow (David Strathairn) is the stern paterfamilias to his eager young crew. Drawn into a toe-to-toe showdown with Wisconsin’s red-baiting demagogue, Sen. Joseph McCarthy, Murrow faces a hurricane of forces.

McCarthy’s wild accusations of Communism and media bias—supply your own Fox Network parallels here—could destroy careers and ruin lives among Murrow’s colleagues. Murrow’s boss, William Paley (Frank Langella), could pull the plug on his suddenly controversial See It Now show—if the sponsors don’t flee first. And there’s the overwhelming sense that, at the height of the Cold War, if journalists don’t stand up to the big lie at home, McCarthy could pave the way to a totalitarianism as bad as anything abroad. Make no mistake, this film is also black-and-white because of its message. For Clooney, son of a TV newsman, journalists can be heroes when they meet untruth with truth, standing up to power instead of cowering behind “fair and balanced.”

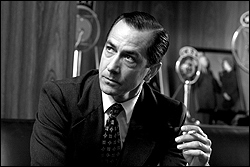

And yet, as superbly underplayed by Strathairn (see interview), Murrow is not a man without feelings. As McCarthy begins attacking him and his staff, as Alcoa yanks its sponsorship (causing him to personally underwrite one program!), he shows the strain familiar to a man who reported in live radio broadcasts during the London Blitz. Strathairn’s pinched eyes and tightly clenched cigarettes—lung cancer would kill Murrow by 1965—give you the rattled sense that he still hears those bombs falling. McCarthy is an echo of Hitler, who also invoked the Communist threat, but Murrow can’t say it in those terms; ethically, he’s bound to fairness, not polemics. He needs to drown this rat in his own words. Without any easy actorly mannerisms, Strathairn’s Oscar-worthy performance reveals a conscience confronting the unconscionable—everything internalized and honestly weighed that today, with Bill O’Reilly and his blabbermates, is simply pumped into the 24/7 hot-air machine.

MORE THAN NOSTALGIA for a simpler time when epochal decisions were made by a few white men (plus one woman, Patricia Clarkson) wearing dark suits, Clooney obviously has some contemporary points to score. Anticipating McCarthy’s inevitable line of counterattack against those who dare question him, Murrow warns, “Anyone who criticizes must be a Communist.” Sound familiar?

Clooney frames the movie’s main action (a few months of 1953 and ’54) with a speech in which Murrow later attacked his own industry for using its power “only to entertain, amuse, and insulate.” Clooney leaves out the denouement of Murrow’s career, when game shows and lack of sponsorship dropped him out of prime time (he left CBS in 1961). His producer, Fred Friendly (here played by Clooney), lasted longer but quit for the same reasons—the network ran I Love Lucy reruns instead of Senate hearings on Vietnam.

Granted, Clooney is complicit in that ever-expanding, profit-centered entertainment universe (Ocean’s Thirteen, anyone? Fourteen? Fifteen?), like his Fox antagonist O’Reilly. Maybe for that reason, Good Night doesn’t feel like a straight feel-good hagiography of its subject. There’s some mea culpa to it, and I hope it makes viewers feel guilty, too. Not that we should know every detail of this episode in broadcast history, but can’t we tear ourselves away from Britney and Kevin long enough to follow today’s news? As Murrow’s career arc proves, the finest journalism is made in vain if nobody watches.

PALEY WARNS MURROW, “People want to enjoy themselves. They don’t want a civics lesson.” Well, Good Night accomplishes both. Clooney loves the early-NASA vibe at CBS, the wonderful old microphones and headsets, the clacking Royal typewriters, the newsreel prints wet from the lab as they’re projected on the wall. There’s a bit of ER as writers and producers race around the studio, critical copy in hand, and Clooney does a great job pacing the pizzazz, then letting Murrow slump in the darkness, silent, contemplating what to do next.

His cast is aces, too, nobody asserting their role over its place in the newsroom. Clarkson and Robert Downey Jr. play secretly married Murrow staffers; there’s a nice joke when she helps him pick out a tie in the morning—”The blue one,” she says of two choices he holds up, identical in a black-and-white movie. Jeff Daniels and Ray Wise also make strong impressions as conflicted CBS men, but the most screen time (after Strathairn and Clooney) goes to an unlikely new star: McCarthy himself. Since there’s such a wealth of real footage from the Senate hearings, he and his original words are woven into Good Night‘s screens within screens. He becomes as much a real, living presence as Murrow, making the film almost a docudrama— and I mean that in a good way. (There also in the Senate gallery are Roy Cohn, Robert F. Kennedy, and Missouri’s wonderfully blunt Sen. Stuart Symington; for more of them, look for the 1964 documentary Point of Order on DVD, New Yorker Films, Oct. 25.)

Of course today McCarthy is a big, fat piñata caught in his lies. No modern Rove-era politician would be so monstrous and un-self-aware (on TV at least). Yet, some people, like conservative pundit Ann Coulter, argue he wasn’t all bad. And there are two sides to every story—just not equal sides, as Clooney reminds us. “We all editorialize,” says Murrow. Thank God for that.