Can curating an art exhibit be an art form in its own right?

“150 Works of Art,” a generically titled show of photographs, paintings, and video from the Henry Art Gallery’s permanent collection, meets that test. It’s a surprising, cleverly staged show dating from 1850 to the present—a smorgasbord of art that is as much about how we display and view art as the art itself.

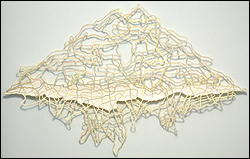

The project is a collaboration between the Henry’s chief curator, Elizabeth Brown, and the Seattle-based art-architecture team Lead Pencil Studio, aka Annie Han and Daniel Mihalyo. Lead Pencil had already been tapped for another site-specific project now on display at the Henry—”Minus Space.” That installation tries to re-create—using burlap and fake grass—the hillside lost when the museum’s awkward expansion was grafted onto the Henry in 1997. Sparked by Han and Mihalyo’s investigation of the museum’s space, Brown invited Lead Pencil to conceive a fresh way of showing a sampling of the Henry’s collection—which spends most of its time reposing in storage.

Don’t come expecting to see masterpieces. Sure, each piece is an effective work of art in its own right. And there are recognized names here: Delacroix, Robert Motherwell, Richard Diebenkorn, Susan Rothenberg, and Kiki Smith among them. But I’d recommend this show almost solely on the original way it’s presented and experienced. I’d also recommend you enter the exhibit from the north entrance, just beyond the “Minus Space” installation, for the most potent visual bang.

If that isn’t enough of a teaser for you, read on. But if you plan to see this show, I’d recommend you stop reading now and see “150 Works” with as few preconceptions as possible. I wouldn’t want to deny anyone the tingle of surprise I experienced seeing this show for the first time. What Brown, Han, and Mihalyo have accomplished is to transform an essentially middling show of art into an experience of wonder.

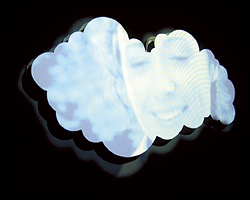

Entering the gallery from the north, you’re confronted with 150 pieces of art turning their backs to you. Each work stands on a simple steel easel, and each has been made uniform on its reverse with plain plywood backing. The space is packed with panels, each stamped in black stencils with only rudimentary information: the artwork’s year of completion, its artist, and title. The easels fill the room with a forest, an orchestra, row upon row of coffins—pick whatever metaphor you like. The walls—the usual repositories of art in a gallery—are left gray and empty. This is a warehouse of art, and the approach has the immediate effect of equalizing each piece. The rows progress chronologically, but other than that constraint, the works are grouped by whimsy. Each work of art is granted equal standing, and the relative obscurity of each demands that viewers create their own assessments and reactions. If you want guidance, you’ll find nothing in the way of curatorial description (for that, consult a computer kiosk outside the gallery).

This approach obviously wouldn’t work for a major show of a single artist—the concept is too distracting and self-absorbed. But it’s perfectly suited for displaying the wildly diverse collection in the Henry’s possession. Many of these works haven’t been on display since Brown arrived at the Henry in 2000.

Brown actually selected the pieces and collaborated with Lead Pencil on the configuration. Viewed from the art side, the installation allows you to see the works in a fascinating continuum of time and space. Since they’re chronological, the older pieces are always visible in the background behind more recent pieces. One can’t look into the future without moving deeper into the gallery.

“We wanted this to be a place you can meander,” said Han. “We wanted people to get as close as possible, walk around the works, relate to them at a human scale.”

The resulting maze is loaded with all sorts of allusions, associations, and visual games. The term “fun” is perhaps bandied about too much in the museum world, but there’s no escaping it: This is a fun exhibit. The works are obscure enough that you can play little guessing games—who would have suspected that charcoal sketch of a woman was a Richard Diebenkorn?

The works are arrayed in such a way that lines of sight become avenues for discovery. Brown and Lead Pencil have created the ultimate visual mixtape, with sly associations. Only looking at their backsides do you realize that works by Kiki Smith and Susan Rothenberg, diagonal from one another, are each titled Puppet. An Imogen Cunningham nude peeks demurely from behind a Weston ghost town and a forest by Emily Carr.

The whole exhibit has a kind of cabinet-of-curiosities feel to it. I’d challenge anyone to name a time when Diane Arbus, French academic painter William Bouguereau, Seattle’s Charles Krafft, James McNeill Whistler, and contemporary Australian artist Ricky Swallow all shared the same room. “150 Works” is almost perverse in its eclecticism—and yet there’s something instructive in finding the odd threads of connection tangled up in the past 150 years of art.

“150 Works of Art” shows through Feb. 26. For more information, call 206-543-2280 or visit www.henryart.org.