Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress

Opens Fri., Sept. 30, at Harvard Exit

Whoever thought there’d be any nostalgia for the Cultural Revolution? The social costs to Chairman Mao’s wrenching initiative, usually dated to 1966–76, are incalculable. Hundreds of millions were affected as urbanites and intellectuals were deemed reactionary and sent to the fields for re-education with the peasants. Anywhere from a half-million to several million Chinese may have died from direct or indirect causes; then, after all that suffering, official policy lurched toward state-controlled crony capitalism, and that fervent period is remembered with shame and anger.

Not so for Dai Sijie, however, a Paris-based Chinese filmmaker who competently but blandly adapts his own 2000 novel, based on his forced re-education during the early ’70s. In the gorgeous terraced hills of Sichuan, laced with ancient stone footpaths, 17-year-olds Luo (Kun Chen) and Ma (Ye Liu) accept their share of humiliation and hard work—hauling sloppy pails of pig shit to fertilize the fields, mining copper with hand tools, enduring the scorn of the village chief. But this really isn’t the focus of Dai’s story, which is remarkably lacking in bitterness. Being the only two in the village who are literate and educated, Luo and Ma are regularly dispatched to town to watch North Korean movies—which they’re then ordered to narrate for the eager villagers back home. Clever teens both, they substitute samizdat plots from their illegal cache of foreign novels (Balzac, Flaubert, Dumas, etc.), which move the villagers to tears.

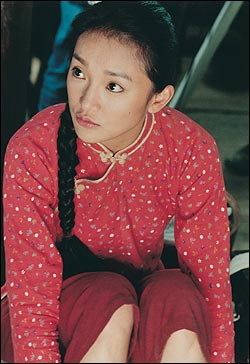

Their best pupil, however, is the local tailor’s lovely granddaughter (Xun Zhou). She gets private tutoring in their forbidden grotto of books: drinking up their knowledge, losing her peasant accent, learning to write, and eventually taking Luo as her lover. Ma narrates the film from his expatriate perspective 30 years later; he also sneakily convinces the village chief that the Mozart sonatas he plays on violin are actually paeans to Mao. He loves the little seamstress, too, but the movie isn’t exactly a Chinese Jules and Jim.

Instead, Dai takes a gentle, sentimental, and thoroughly local view of the period’s upheaval. When Luo and Ma meet again as middle-aged men (a rather abrupt transition), they don’t complain about the copper mining and shit hauling—they just want to know what happened to the seamstress and the other villagers. Their concern is touching, especially as the village is about to be drowned by history. (NR) BRIAN MILLER

The Greatest Game Ever Played

Opens Fri., Sept. 30, at Metro and others

Actually, it’s more like the most boring game ever played. I’ve always held the opinion that golf is a boring game, played by inherently boring people. Well, this adaptation of Mark Frost’s nonfiction account only reinforces my prejudice. Intended to be a heartwarming flick (words that usually chill the heart), the story of Francis Ouimet (Shia LaBeouf), a working-class boy who strives for golf stardom, will only be enjoyed by avid golfers or boring people. Or both, if my theory is correct.

Based on the true story of the 1913 U.S. Open, in which Ouimet defeated veteran British pro Harry Vardon (Stephen Dillane), the film shows golf from many different angles in an attempt to be creative, but mostly it just puts you to sleep. It opens with a little boy awakening to the sound of his family shack about to be bulldozed. This ends up being Vardon, although the connection is unclear. We then jump ahead to a completely different character (Ouimet) and a new scenario.

A poor young American lad, Ouimet longs to become a professional golfer. He practices putting daily on his bedroom floor, eventually becoming a caddy with an amazing swing. Meanwhile, his father, a hardworking laborer, thinks golf is ridiculous and belittles his son’s dream. His mother is more encouraging, but both their characters are forgotten by the film’s end.

In a far cry from his last directorial endeavor, Frailty, Bill Paxton takes a big step away from God-sent demon killers. He also makes a major error in judgment in heading up this lifeless operation. If we wanted to see a golf movie that isn’t boring, we’d watch Happy Gilmore or Caddyshack and be done with it. (PG) MICHELLE REINDAL

Green Street Hooligans

Opens Fri., Sept. 30, at Varsity

Here’s a little song I’d like to sing; repeat after me: “Pretty bubbles in the air! They fly so high, nearly reach the sky. Fawg yar flaff, gor init shite? Arrrr, borrocks! Up yer other’s bunt. Lah blooh agh, g’ooh? Oi!” Finding it hard to follow? Drink another 20 pints, then head-butt someone, and everything will become clear. When a West Ham United follower (i.e., a soccer fan) and leader of the Green Street Elite (i.e., a gang) tells an American hanger-on (Elijah Wood), “We’re a far cry from all that Crips and Blood bullshit,” that’s obvious—Crips and Bloods have a decent sense of style and music. These London louts aren’t going to produce any club hits with their off-key chanting, which is more of a war cry, really. Although when we first meet the chief hooligan (Charlie Hunnam) and his crew in an Underground station, taunting a rival club’s “firm” across the tracks, there’s a little bit of 8 Mile and hip-hop in the ritual insults. There’s also the germ of a good movie here that Hooligans leaves pummeled in the street, teeth scattered on the pavement.

About as subtle as a brick to the face, this flick has three insurmountable problems: (1) Director Lexi Alexander fetishizes the many fights, which we’re supposed to deplore, with her coked-up editing and camera work; (2) the writing is awful, punch-drunk melodrama; and (3) we have to accept that Frodo could become a blood-covered hard man. (Please refrain from shouting, “Use the cloak of invisibility! Use Sting, your magic sword!” whenever he gets in trouble.) Wood may have the Fellowship, but he doesn’t have the gym membership. Brief shirtless shots of him and Hunnam are one reason why the latter convinces as a brawler and the tiny tourist does not. (Though I have my doubts about whether rhyming slang still exists outside the movies; Hunnam and company act like a bunch of Cockney De Niros.)

There’s also a ludicrous subplot about how journalist Wood has been wrongly expelled from Harvard, which suggests how some of Hooligans‘ impotent, self-destructive anger is class-based. (He takes the fall for his evil old-money roommate, ideally played by James Spader inserted by computer from an ’80s flick.) Why is it that these London lads, seemingly left behind by the New Economy, have so much time and rage to spend battling one another? Ivy Leaguer Wood can go home and write a book (perhaps like Among the Thugs, Bill Buford’s excellent nonfiction account of the same turf), as his voice-overs imply. Hunnam and his dead-end mates have only their loyalty and their lager and their testosterone. This permanent underclass is depressingly like that of New Orleans, but don’t expect to see a movie anytime soon called Bourbon Street Looters. (R) BRIAN MILLER

King of the Corner

Runs Fri., Sept. 30–Thurs., Oct. 6, at Varsity

I’m all for movies that send viewers to the bookstore to find the literary source, in which regard a not-so-great adaptation can prompt the same curiosity as a Cold Mountain or Gone With the Wind. Peter Riegert obviously directed this low-key little feature, his first, as a labor of love. It’s only a vanity piece in one scene—saying kaddish at a funeral service—and you easily forgive him for that, because his character, Leo Spivak, has so little vanity or ambition. Leo and the rest of his family are drawn out of Gerald Shapiro’s 1999 Bad Jews and Other Stories, and they live in the everyday texture of life. Meaning while there’s death, adultery, office politics, and a teenage daughter for Leo to contend with, he’s somewhat more concerned with computer solitaire, his young co-worker’s too expensive new trench coat (“Why would you need to zip out the lining?”), and the object of his high-school lust, whom he hasn’t seen in 30 years.

Riegert apparently isn’t the only actor who appreciates Shapiro (who helped him co-write Corner). There’s also Isabella Rossellini (the wife), Eli Wallach (the father), Eric Bogosian (a rabbi who’d rather be at the dog track), Beverly D’Angelo (Leo’s lust object), and Rita Moreno . . . well, I’m not quite sure what her connection to the Spivaks may be. But still—Rita Moreno, and looking fabulous, too.

Leo’s a guy in midlife crisis mode, but Riegert refuses to make him panicked or sweaty or religious about it. (“I’m descended from a long line of crummy Jews.”) If his life’s going down the drain, he’s the kind of guy who then remembers he should’ve bought a rake last fall to get the leaves out of the drain. Even when it’s too late, it’s not too late for him and Corner‘s band of likable characters. They make you want to read Shapiro’s stories and perhaps also meet Riegert, who’ll attend Friday and Saturday’s screenings and conduct audience Q&As afterward. Good thing there’s a bookstore across the street. (R) BRIAN MILLER

My Beautiful Girl, Mari

Runs Fri., Sept. 30–Thurs., Oct. 6, at Grand Illusion

South Koreans have been doing most of the scut work for the Japanese (and American) animation industry for decades, so it should be good news that a few Korean producers and directors are beginning to take control of their own creative destinies. So far, though, to judge by material released in the U.S., the creative results have ranged from pretty poor to dismal. Lee Sung-gang’s 2002 Mari has an engagingly naive look and projects a wistful, nostalgic mood, but doesn’t add up to anything much. Two young males enjoy idyllic summer adventures on the beach of a run-down oceanside town; one of them has occasional encounters with some kind of sprite/pooka/astral being, which don’t lead to anything in particular. After 80 or so very long minutes, a completely unprepared quasi-miracle occurs. On the evidence of Mari, Korean animators know everything there is to know about the technology of animation, but are still a little unclear about the importance of story, character, imagination, humor, and pace. (NR) ROGER DOWNEY

![]() Oliver Twist

Oliver Twist

Opens Fri., Sept. 30, at Metro and others

I’m guessing that Roman Polanski’s is about the 25th screen adaptation of Dickens’ Oliver Twist, and if it inevitably fails to topple David Lean’s untoppable 1948 version, it certainly remains one of the best movies of 2005. Maybe it’s not even meant to challenge the quasi-expressionist glories of Lean’s vision, a moral fable in starkest black-and-white. Polanski makes it more matter-of-fact, as if such horrors could actually happen to an abandoned waif. He should know: It pretty much happened to him in Poland during World War II, and his own hairbreadth escape and ascent to wealthy, Oscar-winning eminence are no more improbable than what Dickens wrote and Lean melodramatized.

Dickens’ London, re-created in Prague, is not otherworldly, and the nightmarish nature of Oliver’s predicament is almost subliminally indicated. At the orphanage, he (Barney Clark) and the other boys sleep in coffin-esque cribs arrayed in grids that echo Auschwitz, but only mutedly. When he’s dragged off to work for an undertaker, it’s not quite a horror movie. His rescue by the raffish Artful Dodger (Harry Eden) and the still more ambiguously beneficial Fagin (Sir Ben Kingsley) is only slightly sinister, and his rescue indeed by kindly, stuffy muttonchop-mustachioed Mr. Brownlow (Edward Hardwicke) isn’t breathtakingly dramatic. In Polanski’s universe, shit simply happens, good and bad.

Clark is putti-cute as Oliver (and in this telling he makes it on looks alone, no kinship with the rich). Jamie Foreman growls generically as a Bill Sykes way more menacing than his mean dog; Lean did a better job complicating his character with hints of guilt, but Polanski’s moral world is simple by design. Leanne Rowe shines as Nancy, Sykes’ unwilling wench and Oliver’s mother figure. Thanks to the unvarnished realism of the film’s many capitalist über-pigs, you can’t help noticing how much they resemble the Bush types who run America today—folks with Fagin’s honesty, Sykes’ compassionate conservatism, and the fairmindedness of Magistrate Fang.

The big news in any Oliver Twist is not oppressed love muffin Oliver but Fagin. Kingsley doesn’t ape the famous original George Cruikshank illustrations as Alec Guinness did. He’s squintier, more insinuating, less Jewish-cartoonish. For all the picturesquely decayed snaggleteeth and scragglebeard and raggy clothes, the key to the character is in the only thing you can recognize as Kingsley’s: those dark, banked-fire eyes. In Betrayal, he managed to make his cuckolded-husband character the bad guy, largely by turning those eyes into obliterating beacons of cruelty. Here, he uses them more variously, to convey twinkling joie de vivre, Fezziwiggian beneficence, corpse-cold calculation, animal panic. In a startlingly unemotional story, most of the emotions are contained behind Fagin’s furry overhanging eyebrows.

The most interesting and revealing thing about Polanski’s otherwise rather impersonal Oliver Twist is the ending. Oliver does escape the gang, the thugs of the underworld, and the establishment, but Polanski refuses to make the ostensibly upbeat ending happy. More than Lean, more than Dickens, Polanski respects the legacy of bloodshed even when it’s overcome. (PG-13) TIM APPELO

Serenity

Opens Fri., Sept. 30, at Meridian and others

This sci-fi Western by Joss Whedon, creator of Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel, is a brainy valentine to fans of Firefly, the short-lived Fox show (available on DVD) on which it’s based. There are several reasons the film probably won’t do well at the box office: no big-name stars; too much story for a feature-length frame; and plot twists that will shock Firefly loyalists but may have little effect on nonfans. Still, there’s enough smart-alecky dialogue and fun ensemble acting to entertain, if not convert, newcomers to Whedon’s quirky vision of the future.

Though it’s much smarter than The Island‘s derivative schlock, you could reduce Serenity to a pitch-meeting catchphrase: “Deadwood gets Lost in Space.” A gaggle of tough-talking, gun-slinging space cowboys (and -girls) rocket through the 26th-century cosmos, pilfering cash from the sinister Alliance and sometimes swearing in Chinese. (Wanna know why? Ask a fan.) Led by Malcolm Reynolds (Nathan Fillion), a cynical veteran of some kind of intergalactic civil war, the crew includes a dumb, brutish firebrand (Adam Baldwin), a geeky pilot (Alan Tudyk), a volatile psychic girl named River (Summer Glau), and River’s earnest doctor brother (Sean Maher).

If this sounds like a collection of genre types, well, Whedon has long excelled at elevating such material to unexpected heights, mostly through sharp casting and a droll, high-minded approach to genres still widely dismissed as lowbrow. His well-paced script does a good job of introducing the crew; after that, it delves into the root cause of River’s grisly nightmares and the efforts of a cold-blooded Alliance operative (Chiwetel Ejiofor) to find and destroy her. Confused neophytes may find solace in several witty fight scenes, a Whedon trademark, in which the jabs exchanged are alternately verbal and physical. And though Serenity is a bit too cerebral for its own good, that same quality lifts it above the vast majority of recent sci-fi flicks. (PG-13) NEAL SCHINDLER