It’s not often that the outdoor world intersects with the very indoor world of visual art. I happen to hike a lot, and for many in the art world, that might as well mean I enjoy an occasional journey to Mars. “I like the idea of the outdoors,” one curator once told me, “I just never go there.”

Landscape has been the traditional bridge between those worlds. American painting has deep roots in landscape— the Hudson River School was one of the first truly American art movements, and landscape has occasionally occupied 20th-century artists as diverse as Georgia O’Keeffe, Richard Diebenkorn, and Michael Heizer.

“Landscapes are culture before they are nature,” contemporary art critic Simon Schama once wrote. And three recent exhibits around town reinforced this observation: “Terra Non Firma,” which recently closed at Howard House; “The County,” at James Harris (through Aug. 20; 206-903-6220, www.jamesharrisgallery.com); and “The American Landscape’s Quieter Spirit: Early Paintings by Frederic Edwin Church,” at Seattle Art Museum (through Oct. 16; 206-654-3100, www.seattleartmuseum.org).

The Church show examines the 19th-century American painter’s early works, and these pictures exemplify what most folks demand in their landscapes: sublime sunsets, thick forests, and wide vistas. What’s fascinating is that these aren’t just snapshots of pretty scenery but complex advertisements for a particular worldview. Nearly all of Church’s paintings include visual subtexts: the foreground of each picture is occupied by a warm little home or a cut stump. Go out and tame the wild continent, these paintings instructed the young nation.

How do you approach landscape in the 21st century, when irony trumps wonder and human economy is quickly destroying most of what’s left of the wilderness? You can take the realist-conservationist route, as Subhankar Banerjee has done in his lovely series of photos of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge now at the Burke Museum (through Dec. 31; 206-543-5590, www.burkemuseum.org). Or you can deal with the nonhuman world in a more indirect, oblique way, as did many of the paintings in “Terra Non Firma,” a satisfying group show at Howard House this past month. The approaches ranged from the pseudo realism of Cameron Martin’s flat, monochrome painting of Mount St. Helens to Mark Danielson’s minimalist, graphic-design-inspired paintings of modernist houses threatened by lurking natural disaster.

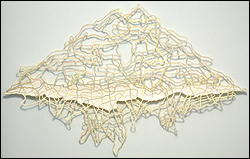

The Romantic sublime—nature seen as something of deep, wild beauty—makes a welcome resurgence in Claude Zervas’ masterful show “The County,” now showing at James Harris. Zervas, a Bellingham native, takes the high country near the Nooksack River as the subject of computer animation, photographs, and inspired sculpture. But again, this is landscape approached sideways rather than head-on.

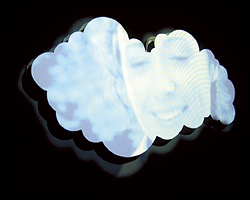

The masterpiece of the show is Nooksack, a sculpture composed from a series of tiny fluorescent tubes. It’s a near-abstract, three-dimensional map of the Nooksack River watershed—the three forks of the river descend and merge in a river of light. But apart from its literal origins, the piece stands on its own as an elegant and satisfying composition. This is minimalism that acknowledges the outside world—not the austere transcendentalism of Dan Flavin or Robert Irwin, but a minimalism that nods to the presence of a world beyond Manhattan and Seattle. Even the streamlike tangle of power cords evokes the flows (whether of water or hydroelectric-generated electricity) that are an essential feature of the Northwest landscape. In all these works, Zervas has accomplished quite a feat: He hasn’t re-created the literal beauty of wilderness so much as the wonder one experiences seeing it firsthand. That in itself is a sublime accomplishment.