Gandhi once said, “We may think our actions are meaningless and that they won’t help, but that is no excuse, you must still act.” My history of activism, however, was almost entirely meaningless and very excusable. Sifting through boxes in my basement uncovers a veritable museum of antiquities: dog-eared Pro-Choice placards, jumbled rainbow pride rings on a rusting chain, crumpled flyers urging body awareness. All these remnants are from a time when my being a fighter for the cause du jour was misguided, passionate, and unquestioning.

As a college student struggling with my identity, I sought others like me with fervor. When I finally found them so many years ago, they just all happened to be involved in activism on some level, so I jumped in headfirst. It was easy—I was young, with boundless energy, lots of time on my hands, and a negligible amount of cynicism. By marching, speaking out, or holding gay-ins, I honed public-speaking skills, made lifelong friends, and, most important at the time, met some girls.

What was missing, however, was that crucial piece of the game—actual connection to the issues. None of us really had any profound, immediate ties to the causes we fought for. We marched out of fear that one day we would be disowned, fired, or discriminated against in some other way for being gay, and we believed we were only doing what our community and our elders expected of us.

Soon after settling in Seattle, I started to feel a desperate need to cut the cord from involvement in a seemingly endless stream of failed or substandard campaigns that plagued the gay community (not to mention about a hundred too many silent auctions). The main reason behind this departure was frustration over being obliged simply by my sexuality to represent “the community” by any means necessary. I questioned my effectiveness: Will the movement really be so much worse off if I stay home from Pride? Is our success really dependent on being perceived as a fighting majority? (With the lack of a united front, it’s a wonder we don’t recruit, as the religious right often claims.) Why must I, by default, sign up and march and serve and speak out at every turn? I thought there was something wrong with the notion that, by being an out gay person, participation was my obligation.

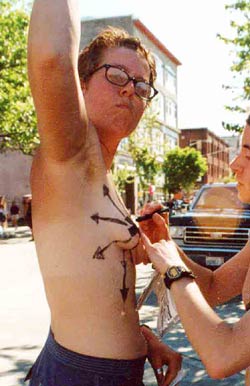

The once revelatory splendor of public circus activism fell to the wayside for this gay white woman in her early 30s. Gone were the days of riding topless on Pride Parade floats, of sporting sunburned breasts while tossing tennis balls onto the White House lawn (giving them balls, get it?), or taking to the podium half-naked, covered in war paint, while urging others into action through sometimes vitriolic speeches. I kept alive the penchant for mild exhibitionism, but the rest remained gathering dust in the form of artifacts and memories.

Then the Republicans came.

I’ve never had a hate crime committed against me until President Bush stated in his 2004 acceptance speech that during his administration he would “uphold our deepest values of family and faith.” I was struck with the painful clarity that he was talking directly to me. I had come to the powerful realization that the president and religious right would continue to threaten my quality of life with blatant discrimination on a regular basis.

Now I look down at the ring on my finger, glance at a photo of my partner and me, and feel a renewed rage at the injustice. Watching the Bush administration flying high as kites on their so-called “morals,” I feel betrayed, set adrift, invisible—an alien in my own country.

And then compulsory activism makes sense. With a revived fervor, I see how the truth and strength behind any movement is when it gets personal. This battle draws so close that it burrows beneath my skin, causing a fury so strangely familiar that I find myself getting up out of my chair and dragging out the placards and war paint—passionate and unquestioning.