After nearly two years with the lights out and the doors closed, Bellevue Arts Museum has reopened. Under the direction of nationally recognized craft authority Michael Monroe, the once-struggling institution aims to become the Northwest’s center for craft, art, and design. To that end, the galleries have been relit, partitions built to section off interior spaces, and carpet added to soften the industrial feel of Stephen Holl’s architectural design.

BAM’s reinvention is a smart move, if not an altogether artistically satisfying one. The Northwest lacks a museum in the same cloth as the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery (where Monroe spent much of his previous career), New York’s Museum of Art and Design, or the Mint Museum of Craft and Design in North Carolina. The Puget Sound region produces so much of what is loosely defined as “craft”—the University of Washington’s ceramics program and the Pilchuck Glass School are just two examples—that BAM’s new incarnation seems a good fit. It also reaches back to the roots of the Eastside museum, which grew out of the annual Bellevue Arts and Crafts Fair, now in its 59th year.

BAM has clearly found a mission, something it formerly lacked. “I’m not interested in making this a miniature Seattle Art Museum or Henry Art Gallery,” Monroe said at the press opening. He also hinted the museum would like to start building a collection—something BAM has never had. This would be great news for local artists and ensure the support of local collectors.

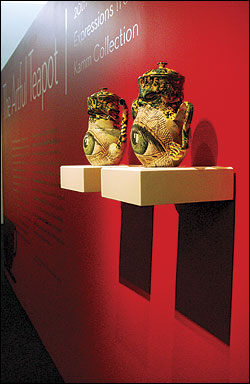

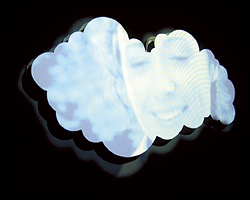

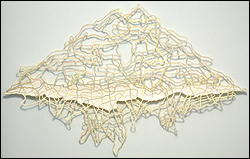

Currently, three exhibits describe Monroe’s vision: “The Artful Teapot,” 250 clever teapots from the Gloria and Sonny Kamm collection (through Oct. 2); “The Artist Responds,” a survey of ironwork by New York state’s Albert Paley (through Sept. 25); and “Taking Shape,” Pilchuck glass from the 1970s (through Jan. 29, 2006).

The teapot collection is impressive in its scope—everything from Michael Graves designs to whimsical pots woven from $5 bills. And Paley’s work is very skilled—his tangled, organic designs take cues from art nouveau, but are contemporary and original. The Pilchuck exhibit assigns historical context to the wildly popular glass phenomenon.

But I just can’t shake the feeling that BAM is offering Art Lite —”fun” art, safe art, art that doesn’t make demands on viewers or elicit controversy.

Take Dale Chihuly (who has a new work in BAM’s lobby) as an example. The man does beautiful work—his glass is intricate, energetic, and skilled. But the power of art is in its ability not only to please us but to challenge us, disturb us, or make us think twice. As Susan Sontag famously put it, good art makes us nervous. Rest assured—your nerves will be safe during a visit to BAM.

“Groundbreaking art doesn’t have to be controversial,” Monroe told me, and I think that sums up BAM’s approach nicely. I suspect having worked at a Smithsonian gallery just steps from the White House has given Monroe expertise in showing high-quality art that offends no one.

This is not to say that craft can’t meet the requirements of rich, satisfying art. Dan Webb does revolutionary things with wood, and local ceramic artists Patti Warashina, Saya Moriyasu, Jeffry Mitchell, and Charles Krafft are doing extremely creative, provocative stuff.

But I suspect Charles is one Krafft that won’t be showing at BAM anytime soon. The artist’s latest provocation is called “Disasterware,” and in addition to the Delft-inspired hand grenades, pistols, and antitank missiles, it includes a teapot. It depicts the head of Adolf Hitler, below which is the inscription “Idaho: Famous Potatoes.” I don’t know about you, but that makes me nervous. Maybe this is a teapot you’ll see at BAM in the near future. But I doubt it.

Bellevue Arts Museum, 510 Bellevue Way N.E., 425-519-0770, www.bellevueart.org.