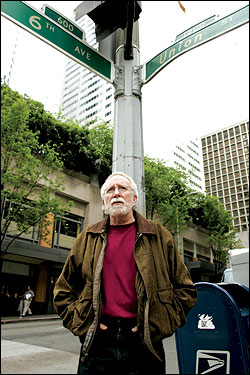

Norm Stamper is standing at the intersection that changed his life. He’s on the corner of Sixth Avenue and Union Street in downtown Seattle, facing the Sheraton Hotel. Five years ago, as the city’s police chief, he was there when he saw a thin line of King County sheriff’s deputies attempt to hold back a sea of protesters surging toward the underground parking lot of the hotel, where delegates to the now infamous World Trade Organization conference were staying. “That was a defining moment,” he says, when he realized the scale of the fiasco before him. The whole mess—complete with charges that the city had become a “police state” and emblematic images of officers decked out in Darth Vader armor—was also a strange and impossible-to-predict defining moment for the career of a man who, up until that point, had been known as a radical visionary who wanted to take policing into new, touchy-feely territory.

“That’s my legacy,” Stamper says with resignation. In town for a few days from his new home on Orcas Island, renowned of late for a scruffy look that includes a beard, the white-haired retired chief is wearing black jeans, a casual brown jacket, and an air of nothing-to-lose honesty. “Thirty-four years in the business—with my passions around domestic violence, community policing, citizen oversight, true partnerships—and for me, it’s WTO. It’s kind of funny. But I do see the irony.”

Hold on, though. There’s a new chapter in Stamper’s career. Or rather a new book, due out this week, and it goes a long way toward putting Stamper back into the progressive, reformist role he long occupied. Published by Nation Books, affiliated with the lefty magazine of the same name, Breaking Rank: A Top Cop’s Street-Smart Approach to Making America a Safe Place—for Everyone is at its best a blunt, juicy, surprisingly writerly account of a life’s work and thought in what he dubs “that tainted, unholy institution called American policing.”

The book openly aims for controversy. The publisher’s description on Amazon.com hails its “provocatively titled chapters, like ‘Why White Cops Kill Black Men’ and ‘Sexual Predators in Uniform,'” as well as its unorthodox positions in favor of gun control and the decriminalization of drugs and prostitution. That much-read Amazon description has already made Breaking Rank the subject of sniping buzz around the city’s precincts. “I don’t know what the hell that’s about,” says Seattle Police Officers Guild President Kevin Hastings, referring to the chapter title on white cops as killers.

All along, I’m thinking, We’ve got this sucker covered. But my cops? They weren’t so confident. . . . They were convinced the city was in for a real shitstorm. (Harley Soltes) |

Beyond the hot-button topics is the core of Stamper’s vision: a demilitarized, empowered, grassroots-based model known as “community policing.” It’s a model that is long past heretical, but it still rubs against the grain among officers who long to do what Lee Libby, criminal justice program director at Shoreline Community College, calls “hairy-chested police work.” Breaking Rank also serves as a reminder of idealism in a profession now preoccupied with the very hairy-chested, post-9/11 task of hunting down terrorists.

Many who read the book will undoubtedly consider Stamper’s ideas on their own merits. But those in Seattle saw his ideas take shape. It’s no secret that the verdict is mixed. “You have to remember that Stamper was one of the most unpopular chiefs around,” says former Mayor Paul Schell, who appears as a brilliant but petulant character in the book. No doubt, Schell has his own version of events, but he’s got a point. Talking to cops now, what’s striking is the criticism Stamper receives not only from the rank and file he tried to empower but from his former top officers. Given the culture clash that Stamper ignites, that’s not entirely surprising. Nonetheless, one senses that Seattle is a lesson that Stamper and the police world still need to digest.

As he describes it in Breaking Rank, Stamper was, from the start, an unlikely cop. The son of a periodically abusive construction worker, he was a troublemaker of a kid who watched the civil-rights movement play out on TV and who viewed cops as disrespectful, useless bullies. He nevertheless drifted into police work in the mid-’60s when, married at 20, he needed a job.

Unexpectedly, he found himself exhilarated by the work and got right into the swing of the prevailing machismo of the time. He says his favorite stunt was “choking people out,” using a hold that cuts off consciousness, while whispering in their ear, “You’re gonna die, asshole.” Like his peers, he exhibited disdain for what they called “pukes” (antiestablishment types) or “assholes” (establishment types without sufficient subservience), both frequently the target of “attitude arrests” on trumped-up charges.

But the transformation into one of the gang didn’t last long. Only a year into his career, he received a shaming scolding by a prosecutor over an attitude arrest. He quickly turned himself into a reformer and found in that role his professional calling.

He was an ambitious reformer, eager to climb up the ranks, and he did what it took to get there. He spent a year on a top-secret assignment “infiltrating the commies and pinkos,” as one of his bosses put it, a secret he has kept until now and one that confirms longtime activists’ suspicions. He also went undercover to bust gays hooking up in park bathrooms and discovered, after several of those he had handcuffed saved him from a lunatic, a newfound empathy for their cause. He encountered domestic violence victims, too, like six kids covered with bruises whose mother had scrawled the police phone number on the wall for the next time Daddy went nuts. Experiences like that helped lead him to the conviction that “domestic violence is a precursor to all other kinds of violence.”

At age 24, after only four years on patrol, he made sergeant—the youngest ever in the San Diego Police Department. He soon became the youngest-ever lieutenant, then captain.

To many, it appeared that Stamper stopped doing the basics. WTO brought that failing into sharp relief, along with a management style favoring delegation and decentralization.

(Harley Soltes) |

Looking back on it now, Stamper can see that his meteoric rise had a downside. “It robbed me of experience,” he admits during a day we spend together in Seattle. Thrice married and divorced, now living by himself in a remote island cabin, he has come to town to celebrate his 61st birthday with friends. He has an easy, expansive way of talking, and it was a moment of particular self-reflection. “I never carried a caseload. I never worked homicide. I never had all kinds of opportunities that, had I not been ambitious, I would have benefited from.”

He had ideas, though, influenced by his short but eventful time on patrol and his liberal politics. And those set him apart. “Norm was wired differently than other cops,” says Jack Mullen, a retired sergeant from San Diego now living in Oregon. Mullen remembers that he and others were “aghast” when Stamper suggested that they write fellow officers speeding tickets. For the officers, the right to speed with impunity was a kind of professional courtesy. For Stamper, ethics were paramount.

His voice gained credence on the San Diego force as a series of enlightened chiefs came to power that, with Stamper’s help, made the department nationally famous. One, Bill Kolender, called for an investigation of racism in a troubled graveyard patrol squad. He assigned Stamper, then a captain, to the task. The year was 1976. What he found, as described in Breaking Rank, was shocking. Thirty out of 31 officers admitted to using racial epithets and demeaning terms. The use of the N-word was just the start. Officers said they radioed “no human involved” for a situation involving blacks, or used the code for an injured animal. One cop refused to give mouth-to-mouth resuscitation to a black woman. Another sang, “Mammy’s little baby loves shortnin’, shortnin’,”to a suspect in the back seat of his patrol car. The only black officer on the squad fell into a weeping jag when he admitted that he went along with it all.

Stamper gets into hot water when he talks about racism among police. In 1998, four years into his tenure as Seattle’s chief, his rank and file exploded over an interview he gave to Seattle Post-Intelligencer columnist Susan Paynter in which he discussed his memories of the racist, aggressive cop culture of his early days on the force. Seattle officers complained he was tarring them for something that didn’t exist here and implied that he was playing to a stereotype. Stamper tells me he also got a load of letters from San Diego officers saying, “It never happened.” He shrugs as if to indicate that they were in denial. Retired San Diego Sgt. Mullen, whose views have come closer to Stamper’s in recent years, doesn’t seem to be in denial when he says, “I didn’t see overt racism, but here’s what I did see: I saw the fact that you saw very few black officers, and all the black officers worked in the black part of town.”

At times, one wonders if Stamper is exaggerating to make his case for reform. Jim Pugel, a highly regarded assistant chief in Seattle who served as Stamper’s administrative aide, remembers questioning the chief’s account of his aggressive behavior in the Paynter article. Stamper had told Paynter about his predilection for choking people out. “Do you think he did that?” Pugel asks. “I don’t think he did. He’s the nicest guy in the world.” With a moralist’s inclination toward self- confession, Stamper also calls himself a serial “spouse abuser” in Breaking Rank, admitting to verbal rather than physical abuse. That surprises his son Matt, a high-tech manager in San Diego, who never heard or saw anything like that, although he notes he was only 2 and a half or 3 when his parents separated.

Stamper insists he’s not exaggerating. He says he came to acknowledge his own dark side through therapy and a particular men’s retreat. “Too woo woo even for this book,” he tells me, which is saying something. (Toward the end of Breaking Rank, Stamper talks of the need to be tough and gentle at the same time, to lean into your fears, and to learn from the samurai tradition of flower arranging before swordsmanship.)

Even if he did fall prey to some degree of exaggeration or overgeneralization, one has to take seriously his account of racism in one particular squad, which was something he documented in a report at the time. Even now it reads as an eye-opening revelation about a time that was well past the civil-rights era.

It was, however, nearly 30 years ago, as were many of the egregious examples of police behavior Stamper cites. So when we first meet in a downtown coffee shop, I ask him what aspects of policing today call for urgent reform. And what aspects police have the ability to reform—as opposed to issues like drug-law reform, to which police can lend an authoritative voice but which are ultimately legislative.

“Treating cops like grown-ups is critical,” Stamper begins. “Too many agencies treat their frontline police officers like dependent or delinquent children, and then they’re shocked when they occasionally act out. This gets to the culture of policing. It gets to the structure of policing. And for me, a pressing need is to systematically and very thoughtfully demilitarize aspects of the police structure.”

Stamper’s views on demilitarization have matured over the years. At one time in the ’70s, when the concept was new, he wanted to put cops in blazers. “Blazers!” he writes with self-mockery in Breaking Rank. “I wasn’t a cop, I was more like a Fuller Brush Salesman.”

But he does still believe that the police disciplinary system needs to be overhauled. “There’s a tendency in police work when a police officer misbehaves to keep the class after school,” he says. Rigid, standardized disciplines are imposed when, in fact, cases should be judged according to their individual circumstances. Crucially, officers should not be penalized for an honest mistake. A case in point, Stamper says, is the shooting of an unarmed African-American man in 1996 by white Seattle police officer Bill Edwards, whose gun went off accidentally as he was trying to lift the man to his feet. The African-American community gave him hell for it, but Stamper decided not to fire Edwards but to put him through firearms retraining.

Stamper also believes that the top-down paramilitary model is stifling, encouraging cops to “look up rather than out.” Where Stamper wants them to look is at the community. And he wants them to think creatively and collaboratively, reaching out to community partners to identify and solve problems. The kinds of problems that police once blew off—not just traditional crime but abandoned beater cars, graffiti, and broken windows— are the kinds of problems that create an environment conducive to crime.

But this is not exactly the version of the “broken windows” theory that former New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani and his police chief, William Bratton, made famous. In ’90s New York, police concentrated on arresting the people who broke the windows and committed all sorts of misdemeanors. That was the model that gave Giuliani and his chief a tough-on-crime image. Stamper concentrates on fixing the broken windows, or at least referring citizens to the people who can, as well as addressing the underlying conditions leading people to become vandals. Stamper’s model gave him a wanna-be social-worker image.

That was the model he tried to implement in Seattle when he arrived in 1994. He established a community policing bureau and put every officer through three days of training in community problem solving, one day of which he taught himself. “Norm was one of the best teachers I’ve ever seen,” says Clark Kimerer, who served as Stamper’s chief of staff and is now a deputy chief. “He was gifted.” Stamper also established a number of advisory councils for segments of the community, including African Americans, Southeast Asians, and gays. He attended community meetings constantly.

He had some notable successes. One of his officers, Tommy Doran, painstakingly worked with businesses and community agencies in the International District to clean up Hing Hay Park and an area adjacent to I-5 known as “the Jungle.” Stamper’s glowing description of Doran’s work casts a redemptive light on the officer, later accused of racism after he fatally shot a mentally ill African-American shoplifter outside a Queen Anne Safeway.

But the rank and file remained largely unhappy. “I heard it directly from a lot of people,” says Kimerer. “All this problem-solving stuff is nice, but I’m putting bad guys in jail.” Kimerer himself had some qualms about Stamper’s model that suggest that more than machismo was at stake. “Problem solving is a pretty involved and complicated enterprise,” he says. “For many situations it’s perfect. But day in and day out, there are also hundreds of situations that require a very straightforward execution of the legal process.”

“You have to have a balance,” says current Seattle Chief Gil Kerlikowske, reflecting on the Stamper years. “There was lots of training in community-oriented problem solving but little in day-to-day skills.” He mentions skills related to officer safety, coping with stress, and handling traffic stops. The department had fallen behind in its first-aid training. While Kerlikowske once served as deputy director for the federal Office of Community Oriented Policing Service, he believes a department can’t live on community policing alone. “You can’t stop doing the basics,” he says.

To many, it appeared that Stamper stopped doing the basics. WTO brought that failing into sharp relief, along with a management style favoring delegation and decentralization. Pugel, Stamper’s former aide and the field commander during WTO, remembers the chief asking some obvious questions before the event, questions like: Who are these protest groups? “I thought they were rhetorical,” Pugel says. “I thought he had the answers.” He didn’t. In fact, Pugel says, Stamper and several of his lieutenants judged it more important to pay attention to an officer’s disciplinary hearing that was going to appear that same week on Court TV. It was a colossal miscalculation born of a lack of attention, Pugel implies. Stamper, he says, “was so visionary out here that underneath we were missing things.”

Would the department have done anything differently had Stamper paid more personal attention to WTO? As Stamper points out in his chapter on the subject (see “Snookered in Seattle,” p. 21), the department undertook an unprecedented level of preparations, even if it ultimately proved inadequate. Should Stamper, as one city report charged in the aftermath, have had many more officers from around the state on hand? “The answer is, I just don’t know,” says Stamper. “Part of me believes that no matter what we had done, it wouldn’t have been enough. The other part is just left wondering.”

Stamper: Free trade, fair trade, what’s the difference?

(Harley Soltes) |

In any case, Stamper took measure of the debacle and a souring relationship with the mayor and resigned days after the conference limply ended. Where was the public to back up this man who had reached out to community groups more than any chief ever had? That’s what police insiders asked themselves. “There was this deafening silence,” Pugel says.

Stamper says he doesn’t spend a lot of time obsessing over the ironic end to his police career. He’s faced ironies before, including one incredibly poignant incident that he shares in his book. In 1972, then a lieutenant, he went out with his San Diego officers on a call. A habitually abusive man was threatening to kill his wife and his 2-and-a-half-year-old boy. In the end, the man sat in his car holding what appeared to be a gun to his son’s head. Stamper, who abhorred violence, shot the man dead, splattering blood and brains on the tiny child. The man wasn’t armed, it turned out, but an investigation deemed the killing justified.

That’s not the end of the story. Twenty-one years later, one of his detectives handed him an incident report about a young man who had threatened to jump off a bridge after the girlfriend he had beaten and threatened to kill broke up with him. That young man was the little boy he had saved. He blamed his problems, in part, on the cop who had killed his father.

Still standing at the intersection that served as a WTO turning point, I ask Stamper what that incident says to him. He thinks for a moment. “It reinforces the nature of the business,” he says at last. He means its unpredictability, its sporadic violence. “At any given moment, a community-oriented police chief or a cop can be called upon to do something that seems to clash with his values.”

That doesn’t mean Stamper is about to abandon his values, though. Detached from day-to-day crises, Stamper is free to do what he does best: thinking, teaching, provoking police officers to think both about his values and their own.