Lords of Dogtown

Opens Fri., June 3, at Metro and others

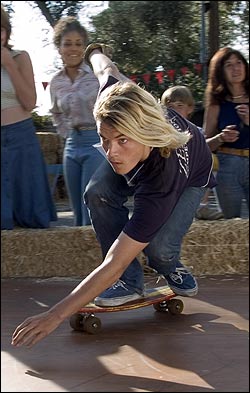

Director Catherine (Thirteen)Hardwicke’s movie about how some impoverished teenage boys from Southern California turned skateboarding into big money is scruffy, sun-drenched monotony punctuated with bursts of ragged energy. That’s probably exactly how it was for a bunch of bored kids in the drowsy summer days of 1975, but it doesn’t make for the most mesmerizing cinematic experience. You sit there wondering why you shouldn’t instead just rent Dogtown and Z-Boys, the 2001 documentary that Stacy Peralta made on the same subject. It would spare you Peralta’s uninspired screenplay here, which includes such earnest clichés as skater Jay Adams (Emile Hirsch) telling his haggard hippie mom (Rebecca De Mornay), “You know, I’m gonna make some cash and get you out of this place.”

Anyone already sold on skateboard culture won’t be entirely disappointed by Hollywood’s version of its vitality. The film has an authentic feel for the fertile, frustrated energies of mop-headed punks with nothing better to do than escape their oppressive home lives on the waves of pre-gentrified Venice Beach, aka Dogtown. With the not-completely-unselfish encouragement of Zephyr surf-shop guru Skip Engblom (Heath Ledger), a restless Adams, Peralta (John Robinson), and Tony Alva (Raising Victor Vargas‘Victor Rasuk) turn their surfing fantasies into a literally concrete reality. Hardwicke captures their reckless excitement at the limitless oceans of opportunity that a summer drought provides in newly drained swimming pools. Soon they’re stars—and, inevitably, bitter rivals—in a burgeoning sport.

Anyone who doesn’t give a damn about skateboarding won’t be caught up in the invention of urethane wheels in the way that, say, a non–boxing buff can get swept away by Rocky. Hardwicke’s fresh cast is casually yet convincingly going for broke, on their boards and off, but these aren’t the most ingratiating kids in the world. (Robinson’s Peralta, perhaps not coincidentally, is gentle of heart; Ledger’s whacked-out turn as the imperiously stoned Engblom, meanwhile, is a worrisome few quirks away from the Val Kilmer Method of Character Acting.) By the time Johnny Knoxville arrives in full pimp regalia as a swingin’ impresario and corporate seducer, there are finally too many dudes saying “bro” for us to be concerned about whether the purity of skateboarding will forever be compromised. (PG-13) STEVE WIECKING

Mondovino

Runs Fri., June 3–Wed., June 15, at Northwest Film Forum

Once upon a time, the word “documentary” meant a film portraying some aspect of life running its course. It was never really that simple, of course: Robert Flaherty routinely “faked” portions of his famous records of tropical and Arctic primitives; and even as beady-eyed and impassive an observer as Frederic Wiseman couldn’t (and presumably didn’t want to) keep his own sensibility out of his films. But is there any limit to just how far documentarians can go when injecting their own ideas into what claims, however disingenuously, to be reportage? None yet reached, because now we have Jonathan Nossiter’s Mondovino, which makes Michael Moore’s recent work look like models of fair and balanced.

Mondovino is about the way marketing and multinationalization are affecting the making and distribution of wine. It’s not hard to distinguish the bad guys from the good guys. The good guys are mostly old and gnarled; they walk, somewhat lamely, nearly always with an old dog at their side. Bad guys wear suits, talk on cell phones, and ride in limos and call lame old men with dogs “fools,” “peasants,” and “hicks.”

The good guys in Nossiter’s film are legion; the bad guys are basically one guy, a jet-setting winemaking consultant named Michel Rolland, who counsels winemakers all over the world on how to make wine that will move in the international market. Rolland is loud, vulgar, jolly, and great fun to watch; he may be, as Nossiter pounds home for 135 minutes, the worst thing to happen to world wine since the phylloxera louse, but he at least seems to think wine is something people should enjoy rather than bow down to and worship. My mind, tastes, and emotions are all on the side of the smallholders who have resisted the march of world wine toward mediocre sameness. But if I were going to spend an hour with anyone portrayed in this film over a bottle of red and some good bread and sausage, I’m afraid I know who that person would be. (PG-13) ROGER DOWNEY

![]() Rock School

Rock School

Opens Fri., June 3, at Varsity and others

One of the principal ideas behind Don Argott’s debut documentary, Rock School, is summed up in its first five minutes by an adorable, adenoidal little boy. Wearing an Angus Young–style shirt and tie, 9-year-old drummer Asa explains that “AC/DC’s really easy, all you do is . . . , ” then bangs out a beat that every AC/DC fan will immediately recognize. Rock music isn’t rocket science, and the point is well-made by the students of Paul Green’s irreverent Philadelphia-based music school. But Argott’s film would be pretty one-note if all it did was show that elementary-school kids can play elementary riffs.

Fortunately, Rock School is really about relationships—primarily the ones between Green and his students (ages 9 to 17). And it’s about how those relationships push young musicians past 4/4 rock rhythms, all the way to a Frank Zappa festival in Germany.

Anyone who has played in bands will recognize Green as that guy who always took it a tad too seriously. He confesses to having failed at the rock and roll dream of making it big, although he also says he’d only want to make it big if he could make it big in 1972. Still, it’s clear that he’s living out some vicarious fantasies through his students, but that would only be a problem if they weren’t also having a genuinely good time and benefiting from his outside-the-box pedagogy.

Green’s star pupils are C.J., a preternaturally talented preteen guitar player whom Argott paints as a mini Carlos Santana, and Madi, a high-school-aged Sheryl Crow–ish singer/songwriter who moonlights with the Friendly Gangsters, a Quaker rap group. Dry-ice clouds surround confident C.J. wherever he goes, while Madi needs—or does she?—cajoling, editing, and lots of direction from Green. Perhaps reminiscent of Jack Black in School of Rock, Green tells us he utilizes the kids’ aptitude for learning without actually treating them like kids. You do get the sense that Green would scream and carry on with his shtick even with his mother.

Argott gets some narrative shape for his documentary as it culminates with the kids’ big performance at the Zappa fest. Music fans will recognize that these particular students are beyond AC/DC; Zappa was a complex composer, and the students have expertly mastered his music. Even if you’re not a Zappa fan, it’s hard not to be thrilled by C.J.’s deft solo and Madi’s slightly hesitant but bright smile when her band nails the toughest song of the festival.

You do worry about these kids, however—about their stars burning too bright too soon. Will they burn out or fade away while juggling their chores and homework? We’ll have to wait for Rock School 2 to see. (R) LAURA CASSIDY

The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants

Opens Wed., June 1, at Metro and others

Let me get this off my chest: I cried during this movie. Not just a single tear, but the cheek-puffing, nose-leaking, heartbreaking kind of a crying that I haven’t experienced since the last dance at my senior prom. For someone so skeptical of each new chick flick, I was hardly excited to see a bunch of 16-year-old girls prance around in a pair of magical pants. After all, the movie was adapted from a book beloved by preteens and mother-daughter reading groups.

Sisterhood follows the enduring friendship of four best friends, chronicling their adventures all over the world. Each girl is challenged by tragedy, yet all overcome it through the power of friendship. The dynamic ensemble is played by America Ferrera, Alexis Bledel, Amber Tamblyn, and Blake Lively, with plenty of chemistry among them. Best is Bledel, who finally gets away from her Rory Gilmore wit and confidence, here exuding a shy, modest beauty.

Maybe I fell for the Pants because I was reminded of my very own dear sisterhood, notwithstanding my initial reservations. Among the book’s devoted readers, you can be sure that tears will roll and mascara will run. (PG) NICHOLE BOLAND