![]() Biro

Biro

Empty Space Theatre; ends Sat., April 23

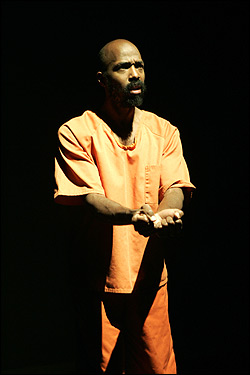

Ntare Guma Mbaho Mwine’s solo piece isn’t an easy show. As conceived, written, and performed by Mwine—who also took the evocative accompanying photos hung in the Empty Space’s lobby gallery and projected onto the production’s background scrim—Biro wants to be both intensely personal and insistently universal. It takes on AIDS, African despair, U.S. ignorance, the “open secret” of illegal immigration, and the tensile but sometimes tremulous collection of incident and error that makes up any one person’s existence. You, meanwhile, have an hour and a half of uninterrupted company with Mwine’s steely ambitions, 90 minutes to digest an accent, culture, and consciousness that are initially foreign. That the production is real work—for him and for you—is a given. That it eventually gets under your skin and stays there is a gift.

But it is work, and, for a while at least, it can be daunting. Mwine, a lean, good-looking man, enters into a square of light in an orange prisoner’s uniform and begins his tale as the title character, a Ugandan expatriate with AIDS, imprisoned in the United States after an arrest over a drunken brawl exposed his phony Social Security number and an old allegation of petty theft. Mwine has spent the past 18 years documenting the people of Uganda (he is a first-generation Ugandan-American) and his studies show, maybe too much. Biro is a composite of real voices, and at times Mwine’s concentration on the ardent melodiousness of those tones—the swooping, singsongy ups and downs of his accent—means you can find yourself hearing only the cadence and not the content of what he’s saying. You have to make your ear relax and hope that Mwine, too, will soften his responses.

He does—which says either that you just need time to get used to the transformation or he does, or some part of both; but, in any case, by the end Mwine is Biro as surely as you are you. And whatever you suspect the artist will make of Biro’s circumstances, you’re probably wrong. Biro—and Biro—is never a simple political symbol; Mwine’s triumph here is a difficult but complete immersion into the whole of a human life. As Biro relates just how he ended up in what seems increasingly like the trap of American apathy, you’re never far from the familiar heart of a common man. Biro’s experiences are nothing like yours—he came of age all at once as a teenage revolutionary soldier battling the tyranny of Idi Amin and Milton Obote (“who quickly killed twice the people in half the time”)—but Mwine communicates them in a way that taps into the everyday fervor and frustration that propel each of us through our tribulations. Not since Barbara Ehrenreich’s Nickel and Dimed has there been such a wry, deft skewering of the absurd exploitation of low-wage workers in this country—applying for a position as a stockroom boy, Biro is asked, “Where do you see yourself in five years?” And you’ll never hear a more eloquent explication of how and why AIDS spread so quickly through Africa (Mwine’s empathy encapsulates the reckless fatalism, hopeless boredom, and assumption of invincibility that are, clearly, not the exclusive property of that continent).

Mwine makes Biro a man to know, and his intimate attentions leave you wondering how many more lives there are like this, how many more stories there are waiting to be told. When Biro finally reaches out and says “Please help me” with a quiet, vulnerable fury, it doesn’t feel didactic. It feels necessary. STEVE WIECKING

![]() Othello

Othello

Center House Theatre; ends Sun., May 1

Presumably, enough has been written about Othello over the centuries that we can skip right to the good stuff in Seattle Shakespeare Company’s production, so let us now commence praising Hans Altwies—a bald, lanky, comely fellow who sinks his fangs into the role of Iago with such perverse, comedic, omnisexual voraciousness that he sends concentric ripples throughout the whole production. Fate, character, and desire whip like a dynamo in Altwies’ portrayal, leveling everything in its path. He becomes inevitability incarnate, a force of nature, yet also just a man whose loathing is the empathetic chill that makes us squirm. This, exactly, is the stuff of tragedy, and to see an actor of Altwies’ caliber so manifestly possess it is a precious moment, and one can only hope this moment receives the audience it so richly deserves. Yes, he’s that good.

Fortunately, there’s no need to speak of saving gestures here. The rest of the cast are also skilled, and the conceit of excising all subplots from the drama, turning it into a streamlined “chamber” piece of wickedness, only amplifies the production’s strengths. The narrative is lean and mean, bearing down on the impulsive drive of Iago’s plot with a single-minded purpose, moving with a relentless atmosphere of suspense. As Othello, William Hall Jr.’s deep, honeyed baritone and mannered, deliberate gestures lend the part a patrician air, and when the shit hits the fan, his snarls and guttural growls betray a tortured beast of desire, a great man trapped. The lovely Jennifer Sue Johnson (who also plays Bianca) is striking as Desdemona, a creature torn by self-effacing love and Christian dignity. Rounding out the small cast are Amy Thone (Emilia/Brabantio), John Bogar (Cassio/Duke), and Dan Dennis (Roderigo/Montano/Lodvico), all of whom shine in difficult double and triple duty.

Director Russ Banham displays a gracious liberalism in allowing his actors to bring their own quirks and interpretations to bear on their parts, and you can almost sense his gratitude at the good results. If the mark of a great director is to alternate between offering the firm but gentle hand of guidance and then letting go, Banham has arrived at grace. This fine production is an excellent example of the manner in which Shakespeare, in the right hands, is infinitely made afresh. A thousand angles are refracted through interpretation, and this time around, one sees Iago in a new light, the combined result of Altwies’ top-tier performance and the director’s daring to fire the Bard through the textual canon, stripping everything but the essence. The effect is as swift and piercing as a shot in the night. RICHARD MORIN

The Constant Wife

Seattle Repertory Theatre; ends Sun., May 1

Seattle Rep’s handsome magazine Prologue says Somerset Maugham was “the bridge between Wilde and Wilder,” but The Constant Wife is more like a porter bringing a weighty Victorian message from Ibsen into Coward’s glittering Jazz Age drawing room. Maugham’s social- message farce raids the private lives of himself and his embattled ex-wife, the celebrated interior designer Syrie Wellcome Maugham, whom he deserted constantly to globe-trot with his true love, young drunk Gerald Haxton. Poor Syrie: Her previous husband, pharmaceutical tycoon Henry Wellcome, used to desert her to hunt for white tribes in Africa, to disprove Darwin; at home, he’d beat her with South African cattle whips. Maugham whipped her with words.

In his play’s enchanted chamber, he transforms himself into John Middleton (Jonathan Fried), respected surgeon and heterosexual philanderer, and Syrie into his long-suffering wife Constance (Ellen Karas), while director Kyle Donnelly stylishly installs them in a striking black-and-white deco set by Kate Edmunds. Fried’s John is abundantly funny in a broad fashion, examining the flapper Marie-Louise (Bhama Roget) beyond the bounds of the strictly professional. The affair scandalizes Constance’s envious single sister Martha (Emily Ackerman), while their unflappable mom (Lori Larsen) eloquently chalks it up to standard male garbage-dick behavior, and advises indifferent acquiescence. But when Constance’s pal Barbara (Anne Allgood) offers her an interior-design job, providing financial independence, John’s power over her erodes. And when her tall, handsome lug of a lifelong admirer Bernard (Mark Elliot Wilson) returns from abroad to court her anew, John is in water hotter than Ibsen’s Nora ever cooked up for her husband.

Will John and Marie-Louise get away with adultery? Will Constance go away with Bernard? The answers are too easily foreseen, and Maugham takes way too long setting ’em up and knocking ’em down. Though the epigrams are often delightful and the farce funny, the play utterly depends on a 1926 audience’s shock at Constance’s matter-of-fact demand for sexual and economic equality. Lacking that, she seems a chilly cipher. When Donnelly has Karas signal her inner grief, we don’t buy it—she’s not a suffering spouse, just a hectoring lecture on modern morals.

Everyone seems remote, as though glimpsed through the wrong end of the opera glasses. Karas is strong and sharp, but cool, abstract, and sexless. Roget wriggles well, and Donnelly gives her one scene reminiscent of ecdysiast Adelaide in Guys and Dolls. As Marie-Louise’s neglectful zillionaire cuckold husband Mortimer, Charles Leggett hams it up just enough. Nobody falls down on the job, but nobody matches the work of Lori Larsen as the cynical defender of patriarchy; those heavy-lidded eyes are perfect for dry irony, and her droll delivery ideal for Maugham’s tone.

Maybe Constance isn’t really Syrie at all—she’s the Maugham character, and she has only cold contempt for the sham of marriage. Maugham once said that sincerity in society is like an iron girder in a house of cards. Constance’s sincerity is icy and harder than iron. She’s funny, but she isn’t kidding. TIM APPELO

![]() Death of a Salesman

Death of a Salesman

Capitol Hill Arts Center; ends Sat., April 30

Willy Loman is the quintessential American archetype, a permanent part of our cultural DNA. He exists as a singular howl of protest against the brutal inhumanity roiling at the heart of the American dream. Say “great American play,” and most folks think Death of a Salesman; even those who’ve never seen it know the name. By this point, attention has been paid—a lot of attention. Director Aimee Bruneau and her crew at CHAC do little to combat such considerable cultural baggage, opting to give the piece as literal a reading as you could hope to see.

It’s a good call; there’s no need to trick anything up. Ironically enough, it’s the dated aspect of the play—the hearty, gee-whiz athleticism of Loman’s sons Biff and Happy, the sunshiny glint of Willy’s corporate platitudes, and the grinding miles of his traveling salesman—that ultimately reveals just how timeless Miller’s masterwork is. What’s so satisfying about Bruneau’s faithful reading is that this truth still registers as a shock, and Loman’s dissolution retains all its ability to break our hearts. Part of the pay-off of this production resides in mentally substituting the social desiderata of one time for another: Behind the rounded aluminum door of the Lomans’ fridge is the same prefab crap we live with, and some of us still have to pay it off with our souls.

David S. Klein takes the lead, and the good news is his performance is wonderful. Full of bluster and puck one moment and the next almost crushed under some unfathomable weight, Klein allows the audience to feel the inarticulate anxiety that compels Loman’s every move; he fills his role with a deep, abiding vulnerability. Also good are Garlyn Punao as Biff and Sherry Narens as Linda Loman, family members writhing in helplessness, and Troy Fischnaller, who’s almost perfect as the ingratiating and eager-to-please Happy, the offspring who threatens in the end to walk more than a mile in his father’s shoes. Physically an unlikely looking clan, these four forge a symbiotic bond through their forceful, tender performances.

With the recent death of Arthur Miller, the show has been touched by a sad, timely relevance. Perhaps his passing, which occurred during rehearsals of this production, inspired Bruneau to play it straight up. Whatever—it’s the right choice at the right time, a fitting tribute to a great American writer. RICHARD MORIN