The lights dim; the babble of the audience, already slightly tipsy on complimentary bubbly, fades away. With a mighty crash, rumble, and chuff, an offstage locomotive accelerates toward us. Just as the racket reaches its peak, a comically tiny two- dimensional steam train noses timidly into view, halts, and debouches a variety of human oddities, costumed for a jaunt on Agatha Christie’s Orient Express. “Native bearers” tote an immense sarcophagus through the audience and set it upright onstage. The show has begun.

The toy train has chuffed unobtrusively out of sight, but in a way, its engine is still running and won’t really stop for the next three hours. The new version of Teatro ZinZanni’s Dinner and Dreams (playing through Sunday, May 15, under the red velvet roof at Sixth Avenue and Battery Street; 206-802-0015) is, as usual, full to bursting with clowns, jugglers, contortionists, dancing waiters, a trilling diva, and a raunchy torch singer (the fabulous Martha Davis of ’80s pop act the Motels) got up as Cleopatra. It’s a dazzling but dangerously diverse assemblage; the adhesive holding all the bits together—supporting, punctuating, bridging every moment to the next—is music.

Norman Durkee has been musical director of Teatro ZinZanni since its first show (appropriately titled Love, Chaos, and Dinner) opened in Seattle in 1998. But the title “music director” doesn’t begin to describe his function. With Norman Langill, founder/leader of Seattle production powerhouse One Reel, Durkee was a co-creator of this indescribable entertainment salmagundi: part dinner theater, part circus, part audience- participation unreality show. His aesthetic, honed by decades in branches of show business from ad production to opera, is so closely aligned with Langill’s (call it “high-concept lowbrow” for lack of a better term) that they share many creative tasks usually kept strictly apart—casting, shaping the show, constantly rewriting and retuning it as new acts join the lineup.

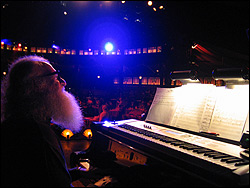

But Durkee’s most important contribution to ZinZanni’s night-by-night success is himself. He is virtually always there on the bandstand, a portly figure in profile bearing more than a passing resemblance to Johannes Brahms (who, let us not forget, is said to have played piano in a house of ill repute in his youth). He shares the stage with virtuosi—violinist Tom Dziekonski, Hans Teuber on horns, percussionist Luis Peralta—but they function as virtual projections of the Durkee personality. He presides over the show like an onstage stage manager, sometimes urging things on, sometimes gently applying the brakes, and often stepping momentarily into the action with a musical gag or comment of his own.

His tone of the moment depends on the moment. With headliner Frank Ferrante (“Chef Caesar”) he becomes half of a baggy-pants comedy team, supplying improvised riffs to complement Ferrante’s inspired Groucho-isms. For the marvelous young Vietnamese juggler Tuan Le, he meticulously underscores the tightly choreographed routine beat-by-beat, which Le used to perform to a prerecorded tape patchwork. It’s a stunning exhibition of supportive synergy, testimony to the trust Durkee inspires in his co-workers; if you’re seeing the show for the first time, it may not even cross your mind how astonishing that is. Durkee’s is a rare combination of talents and one reason One Reel has had a hard time finding an equivalent artist to power the San Francisco edition of the show—it needs someone who can simultaneously mastermind the performance and disappear without a trace into it.

In retrospect, Durkee’s whole life seems to have been preparation for ZinZanni. A piano and performance prodigy from Seattle’s far South End, Durkee got his first big break working for Seattle Opera’s youth program, where he created a touring “opera” for kids with director Arne Zaslove. That led to his appointment to lead the band for the opera’s memorable production of the Who’s Tommy at the Moore Theatre, which gave the young Bette Midler her first starring role onstage. After a stint in Santa Monica as composer in residence, idea man, and jack-of-all-trades at the adventurous Chiat-Day ad agency, he returned to the Northwest to make a tidy living writing, composing, and producing commercials.

Never satisfied merely to write a jingle and pick up his check, Durkee over the years has composed scores for modern dance and ballet works, and developed a kind of binaural “radio theater.” It’s hard to describe his “sound.” He can shift from one genre to another without missing a beat, drifting from outright knockoff (the music for the opening train sequence at ZinZanni may sound more than a little familiar to fans of Stravinsky’s Firebird) to sly allusion to what sounds at first like chaotic collage.

When you know that Durkee’s favorite composers are Kurt Weill, Nino Rota, and Hollywood cartoon scorer Carl Stallings, the whole bizarre assemblage begins to make sense. The angular, plaintive cabaret-inflected melodies of Weill may not seem to have much in common with Rota’s oom-pah circus tunes or Stalling’s raucous slide-whistle and cymbal-crash soundtrack, but all share a love of the impure, a sense of irony, and a distinct whiff of greasepaint.

Teatro ZinZanni is a natural extension and evolution of Durkee’s musical aesthetic, incorporating even more extreme flavors and textures into the stew—four courses of gourmet food, vaudeville acts embedded in a gossamer plot, a burlesque’s bumps and grinds and blue humor beside Puccini’s soaring “Nessun dorma,” and running constantly beneath, sometimes rippling, sometimes roaring, the mighty engine of Durkee’s Orchestra de Ville, whipping all the ingredients into memorable froth. Next time you go to ZinZanni—and you probably will—enjoy the show, but spare an occasional thought for the big bearded man on the bandstand. Unless you’re very lucky, you won’t see his like soon again.