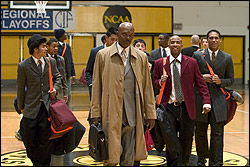

Coach Carter

Opens Fri., Jan. 14, at Oak Tree and others

In 1999, Ken Carter, part-time coach of the basketball team at Richmond High, 10 miles and worlds away from San Francisco, shocked his community by locking his championship-bound players out of the gym for a week and sending them to the library instead. They’d won 13 out of 13 games, but Carter was more interested in other numbers. One-third of his 45 players had failed to fulfill the contracts he’d made them sign: to be punctual in class and maintain a 2.3 GPA—higher than the 2.0 the district required of athletes.

His bold move probably cost Richmond the district championship, but several of the kids went on to college—from a school that sends almost nobody to college—and his own son went to West Point. Coach Carter became a star, trumpeted by the national press and by Rush Limbaugh, who told him his hard-core approach was precisely what Limbaugh was trying to accomplish on his radio show. Carter sounded skeptical of the fat hypocrite junkie, who isn’t the best friend minorities ever had, but he used his fame to become an inspirational celebrity and motivational speaker.

Understandably drawn to the story, Samuel L. Jackson has a blast impersonating Carter in this new biopic. Jackson stands tall, barking out orders, raising his kids to new heights with tough love. Rob Brown (Finding Forrester) is moving as an athlete whose future is threatened by the billowing belly of his sweetheart (pop diva Ashanti). Rick Gonzalez shows some gumption as a kid torn between basketball and the thug life. The movie itself is inevitably formulaic, longish, and a bit dull, but you don’t have to be Rush Limbaugh to like it. It’s fun to see an MTV-sponsored youth entertainment that isn’t cynically vulgar, and some of its scenes satisfy like a basket sunk from half-court. (PG-13) TIM APPELO

![]() In Good Company

In Good Company

Opens Fri., Jan. 14, at Meridian and others

Advertising executives appear frequently in movies, but they’re usually the villains. In Good Company presents us with two well-meaning ad execs—one at the beginning of his career, one in midlife crisis—and asks us not only to like them both for different reasons, but also to believe that a friendship could develop between them, despite their differences. In both cases, I did.

Carter (Topher Grace) is every hardworking company man’s nightmare: the young turk with an M.B.A. but no experience who rises up the ladder on a fluke and ends up running the ad department at Sports America magazine. Yet Carter is hardly the typical twentysomething jackass horning in on the corner office; he’s on the verge of a divorce, the result of marrying too young, and readily admits to near strangers that he has no idea what he’s doing at work. It’s a credit to Grace’s guileless, naturally comic acting that Carter comes off as a likable person, even as he frantically preaches “synergy” at his first big meeting while suffering the worst flop sweat I’ve seen on film in years.

On the surface, Dan (Dennis Quaid) couldn’t be more different from Carter, his much younger new boss. Dan’s training goes back to a time when deals were sealed by handshakes between men. He has a sweet relationship with his tomboyish eldest daughter, NYU student Alex (Scarlett Johansson). His wife, Ann (Marg Helgenberger), is patient with him, but only to a point. Quaid brings to his character the kind of emotional nuance he showed in Far From Heaven—except that here he’s freaking out, not coming out. All along, Quaid carries his building anxiety in the same place he kept his secret sorrow in Heaven: those big, expressive eyes.

When Alex seduces Carter in her dorm room, oozing sexual authority, the jig’s up. His startled paralysis conveys what we already know: He isn’t in control of his career or his life. How Dan learns of their affair—and what happens next—is the crux of the film, yet the confrontation and its aftermath are much more realistic and thoughtful than the dumbed-down hysterics of your average romantic comedy. Everything’s relative for writer-director Paul Weitz (About a Boy): Just as there’s no such thing as absolutely safe sex, only “safer sex,” life doesn’t provide happy endings, only (relatively) happier ones. It’s a truism that Company acknowledges with a plausible, bittersweet finale. About a Boy ended with a messy family of misfits led by Hugh Grant’s reformed womanizer; Company, less warm but every bit as smart, trades Boy‘s fairy-tale ending for a grown-up resolution that’s more believable. (PG-13) NEAL SCHINDLER

Testosterone

Opens Fri., Jan. 14, at Varsity

If you want evidence of just how ferociously good director Pedro Almodóvar is at what he does, you can either see his latest—the lusty, brooding Bad Education—or you can check out director David Moreton’s ersatz black-comic thriller, a movie that would need Almodóvar’s flair to make it everything it aspires to be.

Moreton, who previously helmed 1998’s well-observed but episodic gay coming-of-age flick Edge of Seventeen, is now reaching into the shadowy adult realms of homo desire. Adapting a novel by James Robert Baker, he and witty Premiere magazine scribe Dennis Hensley have crafted a darkly wry lesson in frustrated queer longing. Graphic novelist Dean (David Sutcliffe) has just been dumped without a thank-you-very-much by Latin lothario Pablo (Calvin Klein underwear icon Antonio Sabato Jr.), whose sudden absence causes the obsessively heartsick Dean to follow the Argentine’s trail to Buenos Aires. Dean is soon stopped in his tracks by an enigmatic cafe owner, her persistently horny brother, Marcos, and Pablo’s lethally vindictive society mother (Sonia Braga, slumming it here in high style).

Sutcliffe’s manly handsomeness is ideal, but the dryness of his wit finally becomes arid. He plays his droll stalker neither light enough for the comedy nor heavy enough for the compulsion; he doesn’t have the maniacal dexterity of a troubled Hitchcockian “straight” man, the nimble imbalance of Jimmy Stewart’s Vertigo flesh hunter. Nor does his director have what it takes to deliver the goods: Moreton does nothing to deepen the movie’s sinister humor into something genuinely fucked up and funny.

Still, it’s an attractive film: Comic-book opening titles amusingly illustrate the Dean/Pablo affair, while cinematographer Ken Kelsch and production designer Jorge Ferrari (who styled the sexier queer Argentine noir Burnt Money) do slick work on a small budget. There’s also enough eye candy for any guy simply wanting a dose of the titular hormone. Sin and skin are sprinkled throughout: Dean rebuffs the advances of Marcos, then catches sight of him giddily boinking the hotel’s delectable bellboy; there’s a promising James M. Cain–ish sexual tussle when, later, Dean slugs Marcos and they then proceed to mash in a passionate fury, bloody lip and all; and an all-too-brief nude flashback proves that Mr. Sabato Jr., who’s having wicked fun, is very much a Sr. in the nether regions. What Testosterone really needs is a director who could show us more of what we’re missing. (NR) STEVE WIECKING

Who Killed Bambi?

Runs Fri., Jan. 14–Thurs., Jan. 20, at Northwest Film Forum

French actor Laurent Lucas has a genuinely creepy presence (hissing voice, menacing underbite), but ironically he’s best known stateside as the straight man to his co-stars’ pathological nutcases. In In My Skin, Lucas plays the patient boyfriend of a woman who becomes obsessed with auto-mutilation. In With a Friend Like Harry, he’s a family man defending home and hearth against Sergi López’s homicidal stalker. Lucas finally gets to wig out in Gilles Marchand’s hospital-set Bambi, in which he plays a physician who pilfers anesthetics to have his way with patients. Nursing trainee Isabelle (Sophie Quinton) suspects something is askew, but the good doctor (who nicknames her Bambi) seduces her into a dreamlike web of . . . well, something. Too vague in its cat-and-mouse play to succeed as a psychological thriller, Bambi fares better as a visual exercise in white-on-whiteness—lab jackets, fluorescent glares, and Isabelle’s own pale skin combine for a sustained atmosphere of bleached-out horror. (NR) DAVID NG

The Woodsman

Opens Fri., Jan. 14, at Varsity and Uptown

The question at the heart of The Woodsman is whether Kevin Bacon’s beautifully calibrated performance as a just-paroled child molester is worth the price of leaving hard-earned common sense at the door in order to enter his character’s world.

It’s a place where Walter (Bacon), back home after a 12-year sentence, can rent an apartment right next to an elementary school, and where a tough-but-poetic detective (Mos Def), who’s shadowing his every move, can fail—along with the school staff—to notice the curly-haired blond guy outside the school playground, luring little boys into his car with moves straight out of cautionary after-school specials. (Only Walter seems to be onto this menace.)

The Woodsman is a first-time film for director Nicole Kassell, who also co-wrote the screenplay with Stephen Fechter, based on his play. Her strength is in her work with actors, not only the more experienced ones but most particularly young Hannah Pilkes, who carries the movie’s most crucial scene with touching honesty. Unfortunately, Kassell is woefully short of hardheadedness about Fechter’s wilder flights of symbolism and metaphor: hardy ivy plants; a bird-watcher named Robin (Pilkes’ character); detectives expert at fairy tales, woodworking, and horticulture. But then, she’s the one who chose “His Eye Is on the Sparrow” as the closing music.

Although the film seems to be treating Walter with distant evenhandedness, it loads its case for empathy, as he struggles for the day when he’ll be “normal.” An expert carpenter, he gets a job at a lumber yard full of women who find his impenetrability challenging. Before long, he’s been seduced by Vickie (Kyra Sedgwick, Bacon’s wife), a tough-talking forklift driver, not the first here to announce that Walter is a man with a secret.

When she finally worms it out of him, his explanation—that he molested little girls ages 10 to 12, but “I never hurt them”—is the good Nazi cop-out (bad deeds/good heart). It brings up two points, which Kassell and Fechter take pains to avoid: Who says his actions did no harm; and if the film truly wanted to test an audience’s open-mindedness, what if he had, indeed, hurt these girls? Where’s our high-minded empathy then?

In The Woodsman‘s muzzy-headed world, such distinctions hardly matter, since in the story’s thicket of coincidences, Vickie turns out to be a nearly perfect choice for Walter, having had more than her share of “getting poked around” growing up with three older brothers. Now, however, she’s their biggest fan, “All strong, gentle men with families of their own.” (As family dynamics go, this is certainly an optional rite of passage.)

Bacon’s lot is to play a shuttered but struggling man, following a script that gives him almost no character history to work from. For a film whose heart is so clearly on his side, it’s jolting to notice that the only time Walter comes alive is when he’s followed the bird-watching 11-year-old, the girl with the little red jacket, to the park. In the picture’s most blithering logic, we’re supposed to applaud the scene’s conclusion, when all that’s really happened is that another child molester has gotten away. (R) SHEILA BENSON