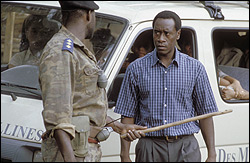

![]() Hotel Rwanda

Hotel Rwanda

Opens Fri., Jan. 7, at Metro and Uptown

In Walter Murch and Michael Ondaatje’s book The Conversations, the wisest meeting of movie minds since Hitchcock/Truffaut, Murch describes the day he rediscovered the legendary lost version of Apocalypse Now: hours of film in which the protagonist is not Martin Sheen but Harvey Keitel, who left after a month’s work. The difference that made the finished movie was Sheen’s eyes: “Marty has an openness to his face, a depth to his eyes, that allowed the audience to accept him as the lens through which they were able to watch this incredible war. Keitel is perhaps more believable as an assassin, but you tend to watch him rather than watch things through him.” Those eyes have lately enabled Sheen to play the wildest dream of half of America on The West Wing: a president with a human face.

Don Cheadle’s face has a still more humane openness, and eyes deep enough to reach his soul—and yours. Even when he’s playing a disreputable lout, as in Devil With a Blue Dress, his eyes enable him to steal the picture out from under Denzel Washington’s generic matinee-idol look. Cheadle tackles the challenge of a lifetime in Hotel Rwanda—or rather, of almost a million lifetimes. That’s how many were cut short in 1994 when the African nation’s Hutu tribesmen murdered their Tutsi neighbors, who had earlier murdered and oppressed them. Americans tend to blame such tribal strife, in Africa or Iraq, on the intrinsic savagery of the local primitives because most of us don’t know how the West created Rwandan and Iraqi ultratribalist strife with its self-serving new colonial map, forcing enemies together and smashing delicate ancient balances of power. Later, the West was too coldhearted to intervene as Hutus hunted Tutsis in the streets, because to do so would mean admitting the error, and true cost, of those boundaries.

How can mass madness be dramatized? Through the eyes of one man, Paul Rusesabagina, manager of the Hotel Des Milles Collines in Kigali, the haute spot of Rwanda’s capital city. Cheadle makes the unbelievable, unassimilable horror real by mirroring it in the large, liquid, extraordinarily intelligent eyes of Rusesabagina, who really saved about a thousand people against all odds as machete-brandishing killers and victims swarmed his hotel and loudspeaker trucks roamed the countryside urging death to the “Tutsi cockroaches.” Schindler had an easier go of it: His Nazi bosses were such order freaks that his factory’s machinelike efficiency kept them at bay. But Rwanda’s ordinary chaos erupted into free-floating mindlessness in 1994.

And how does Rusesabagina pull it off here? By hypnotizing the thugs into thinking that the top hotel in town was and should remain an oasis of humanity on its best behavior, an island of responsibility in a gory sea of anything goes. Only the single moral searchlight of his gaze convinces the killers that the protective light of international law shines on the hotel. He reads everyone’s mind, bribing this killer with 25-year-old Scotch, that one with flattery, another with calibrated threats likely at any instant to get his own Hutu ass killed—and also his Tutsi wife and half-“cockroach” children. With a crucial little bit of help from a rebellious U.N. commander (Nick Nolte), he proves that you can negotiate with terrorists—you just have to be subtler and smarter than they are.

Hotel Rwanda is worth seeing for a performance that, if it doesn’t nab an Oscar nod, will disgrace the AMPAS. As for the rest of the film, director Terry George quite lacks Cheadle’s gift for nuance and subtlety. He previously co-wrote the screenplay for Jim Sheridan’s simplistic In the Name of the Father, and he’s an aesthetic simpleton here, too. Even so, his great and criminally underrated star goes far toward opening our eyes to hearts of darkness—including our own. (PG-13) TIM APPELO

Purple Butterfly

Runs Fri., Jan. 7–Thurs., Jan. 13, at Grand Illusion

Lou Ye’s 2000 Suzhou River daringly transplanted Vertigo to Shanghai and transformed the city’s canals into an urban stream of consciousness. Following the misty River further into genre territory, his Butterfly is nearly as waterlogged and no less stylish—part action flick, part love story, and part posh historical pageant. (The film was trimmed and revised after its unsuccessful Cannes ’03 debut.)

This wildly impressionistic period thriller—set before and during the Japanese occupation of Shanghai—stages Hong Kong gunplay against a moody Herrmann-esque score. Even more adroit in its soft jump cuts than River, Butterfly is a fabulously morose piece of work, perversely filled with time-wasting gazes and cigarette-shrouded silences. The abundance of close-ups is complemented by the paucity of dialogue—as well as a tendency to erupt into extended bursts of chaotic violence.

The only constants are the perpetual monsoon soaking Shanghai and actress Zhang Ziyi’s tragic beauty as a Chinese partisan. Little is said but much is revealed as successive waves of emptiness and paranoia wash over her face and that of the Japanese agent (Toru Nakamura) she takes as a lover. Covers are blown, then minds. Finally, as gunfire breaks out, the entire nightclub erupts in a dance of death—a metonym for the movie itself. (R) J. HOBERMAN

A Tale of Two Sisters

Opens Fri., Jan. 7, at Varsity

Kim Ji-woon’s Korean 2003 horrorfest deserves its thundering buzz as the next Ringu. Stephen King should be so spectacularly talented at summoning spirits to turn an average home into a mise-en-scène of nameless dread. Even though Sisters‘ pace is as deliberate as a little boy riding a tricycle through twin-haunted hallways, the tension builds and never sags, and the film is punctuated with stunning bits to make you risk death by shock and inhaled popcorn.

The cast is fab. Kim Kap-su has a face radiating weary empathy as the family patriarch—he’s stuck in a house of madwomen. His daughter (Lim Su-jeong) is back from the nuthouse, rather defiantly reorienting herself to normal life. But how can she act like nothing’s happening when her shy sister (Mun Geun-yeong), also just deinstitutionalized, is menaced by all manner of ghastly apparitions? And tormented by their tightly smiling but manifestly malevolent stepmother (Yum Jung-ah)? Even when their very normal relatives come for dinner, guests get seized by evil spirits; and slimy, anguished creatures crawl wetly out from under the sink. I wouldn’t advise peeking under any article of furniture in this house—but above all, avoid opening the armoire.

The spirits are scary, if a bit familiar at this point in the conquest of the West by nightmares from the East. (DreamWorks plans an Americanized version of Sisters, à la The Ring‘s Yankeefied Ringu.) Ji-woon has a distinct auteurial signature, gorgeous and very catchy.

Yet here’s my one, very large problem with this film, and Ringu/The Ring: The filmmakers feel zero need to make anything add up to any intelligible interpretation. They hint at dark possibilities: It could be that ghoul’s a ghost or a hallucination; or it could all be the delusional view of a character who thinks she’s another character. I can’t spoil the surprise of the final revelation, because nothing is revealed. If what’s terrifyingly and murkily suggested will suffice, and you feel no need to know what in otherworldly hell just happened, then this is the flick for you. (NR) TIM APPELO

![]() Unknown Passage: The Dead Moon Story

Unknown Passage: The Dead Moon Story

Runs Fri., Jan. 7–Thurs., Jan. 13, at Northwest Film Forum

Utterly unpretentious, organically wayward, homespun, and purposeful without being overly sentimental, this film fits its subject perfectly. Documenting the trajectory of the Portland trio Dead Moon (including the prior solo and garage-rock careers of Fred Cole), Passage is the ultimate punk-rock feel-good flick; there isn’t a band that better embodies the sounds and ideals of its genre while simultaneously inspiring an authentic sense of friendship, family, and truth.

Best known for being the coolest grandparents in music, Clackamas, Ore.’s husband-and-wife singer-songwriters Fred and Toody Cole are in their 50s, yet they’re exponentially better than kids half their age who are many times more commercially successful. Although age is the second-most distinctive feature of the country- and blues-edged rock trio (which also includes drummer Andrew Loomis), Passage doesn’t belabor the issue. A German fan effuses about how remarkable it is that they’re as old as his parents yet infinitely hipper, but for the most part, the movie smartly sticks to chronicling Fred’s ’60s-era psych/soul garage output—and the bands that led up to him teaching Toody to play bass so they could eventually form Dead Moon in 1987. Informing the music of all Fred and Toody’s projects is the personal history of the Cole family; they’re as left-of-center and oddly spiritual at home as they are onstage, and the DIY spirit pervades on both fronts.

Aside from some pretty amazing footage of the Coles’ criminally overlooked proto–new wave band the Rats, Passage is relatively light on vintage live performances—although there is plenty of great musical accompaniment for an entertaining array of old photographs. Extensive interviews with fans and family, Loomis, and Fred and Toody (mostly conducted in the couple’s secluded, self-constructed homestead) complement the performance clips. As Toody discusses raising their kids and Fred explains his strange superstitions and purposefully rustic recording aesthetic, fans will be happy to rediscover what they already know: The reason Dead Moon have triggered an underground, almost familial following at home and in Europe is that behind the affecting, raw, and primal rock, there are three people whose lives are worth listening to. (NR) LAURA CASSIDY