Some people are born wistful. So deeply are the analog early ’70s imprinted on 35-year-old Wes Anderson that rotary-dial phones and transistor radios may come back into style thanks to The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou, which opens Saturday, Dec. 25, at the Guild 45 and other theaters. His latest comedy limps into port coated with the rust of nostalgia and studded with the barnacles of whimsy. That’s not to say it’s a sinking ship, not when crewed by Bill Murray (at the helm), Anjelica Huston, Cate Blanchett, Owen Wilson, Willem Dafoe, and Jeff Goldblum. The Belafonte, as Steve Zissou’s marine research vessel and floating movie studio is called, stays afloat just as long as you want it to and not one knot longer. Like the Tenenbaum household, it’s full of quirky characters and deadpan drolleries. Troubled marriages and grown-but-lost children also figure prominently. For all onboard, like Anderson, the past seems a better place and the present a poor substitute, but everyone knows there’s no reversing course. You could call the movie “wistful-some”; the longing for what one had—or was denied—is almost overwhelming. Yet Aquatic never turns briny with regret. While not a deep picture or an improvement on The Royal Tenenbaums (it’s more like a maritime sequel), it sails a uniquely amusing course through imaginary archipelagos and chimerical sea creatures. Anderson’s charts are fake, but fun.

Beginning and ending at an Italian film festival, Aquatic finds 52-year-old Zissou (Murray) in crisis, “a washed up old man with no distribution deal.” His moviemaking partner has been eaten by the heretofore unknown jaguar shark, his marriage to Eleanor (Huston) is on the skids, and an Air Kentucky pilot named Ned (Wilson) shows up claiming to possibly be his son. Though American, Zissou’s messy life is loosely derived from that of Jacques Cousteau (who died in 1997)—the boat, the crew’s red stocking caps and blue uniforms, the pedagogic and possibly faked undersea movies, the past glories. (Cousteau won three Oscars, then became a staple of somewhat cheesy American TV specials that, one suspects, were an Anderson favorite.)

Besides his wife and (maybe) son, Zissou’s ship of fools includes German lieutenant Klaus (a hilariously needy, Teutonic Dafoe), pregnant English journalist Jane (Blanchett), a guy who sings old David Bowie songs in Portuguese, and some college interns who fetch him Campari on the rocks. (Goldblum plays his much better financed rival, Hennessey, whose modern sea-station equipment, and espresso maker, Zissou commandeers.) “We’re a pack of strays,” says Zissou, and the whole movie has the same bric-a-brac feeling to it: Anderson assembles everything as intricately as a ship’s model. He even pulls the camera back to reveal an entire cutaway diorama of the Belafonte; it’s an ant farm of insecurity.

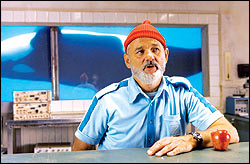

Standing at the anxious helm, Murray wears an air of exhausted entitlement—like Gene Hackman in Tenenbaums—as confidently as he does his tight blue Speedo. Zissou lets his gut hang out over the elastic with all the majesty it deserves. Rebuffed by Jane, he lambastes her as a bull dyke. Knowing that Eleanor has gone back to her ex, Hennessey, he’s not too proud to beg her for the money to fund his latest voyage. He basically swindles cash from Ned. He even gets his own tongue-in-cheek action sequence, brandishing a Glock to defend his ship from Filipino pirates; later, he leads his crew in a shoot-out to retrieve a hostage from these brigands. As with everything in Murray’s career, he both means it and doesn’t. He’s Anderson’s preferred leading man—and for that reason, he should say no to a third pairing—because he’s a self-aware fossil, the dinosaur who expects the meteor to hit.

In Anderson’s Rushmore, Murray also played a sagging midlife guy with hopes for a younger woman, but he simultaneously mocked those hopes. Here, his romantic rival (Wilson) is more formidable, no teenager, and his entire career is in jeopardy. The stakes are higher, yet his response is a higher level of insouciance. Whether he kills the jaguar shark, wins the girl, makes a successful movie, or finds a son—it matters and it doesn’t. His ambivalence is heroic, and at least he’s honest about himself: “A showboat and a little bit of a prick . . . but that’s me.”

Like the fantastical jaguar shark (one of the many fanciful undersea creations by animator Henry Selick), Zissou himself becomes a near-mythic creature. He’s trying to live up to his old movies and one-sheets (which Anderson lovingly creates in all their cheesiness), still knowing that you can’t compete with history. If there’s a point to Anderson’s fusty methodology, all his butterflies on pins, it’s that retro-poignancy: the sense that one’s better days are past. It’s also the same exact theme of his last two movies—and dangerously close to becoming a self-fulfilling aesthetic for his old-young career.