Both Robert Gottlieb’s George Balanchine: The Ballet Maker (HarperCollins, $19.95) and Terry Teachout’s All in the Dances (Harcourt, $22), published this year in honor of Balanchine’s centenary, are written for the general public rather than for the academic or dance scholar. Teachout says so right from the beginning (“This is a short book about a great man who lived a long life”), and though he covers all the major points of Balanchine’s life, the best part of this narrative is found in his lively responses to the dances. He is refreshingly open about his love for the ballets, starting with an epiphanic viewing of Concerto Barocco in 1987, and his writing combines that partiality with a clear description of the action that evokes those feelings. “As [the ballerina] skitters about the stage,” Teachout writes of the “Choleric section” of The Four Temperaments, “Balanchine reassembles the entire cast in a series of sleight-of-hand entrances leading to a finale in which the steps of the preceding theme and variations are rapidly reprised, flashing by like shooting stars.” Balanchine commented once that everything there was to know about him could be seen in his dances; Teachout takes him at his word.

Gottlieb is more focused on the man than on his works. Alongside a distinguished career as an editor (he shepherded Bill Clinton’s autobiography, among others), Gottlieb worked a variety of unpaid jobs at the New York City Ballet, including planning programs and marketing, and had the opportunity to watch Balanchine in many different situations: “Balanchine sat in the middle of the theater, ignoring the hysteria surrounding him, totally focused on the way Merrill Ashley’s . . . Swan Lake tiara sat on her head. That was the one thing he could do something about, and he was doing it.” Both Teachout and Gottlieb mention Balanchine’s five wives, but Gottlieb ties those experiences more closely to the ballets he made for them, in some cases after their relationships had failed. We watch over the author’s shoulder as he watched the choreographer at work.

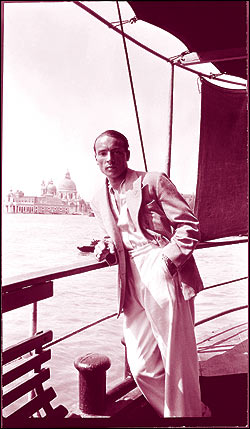

Thanks to a good relationship between public television and the New York City Ballet, a variety of Balanchine’s choreography is available on videotape, but Balanchine (Kultur, $29.95), probably the most comprehensive program, is now available on DVD. First broadcast in 1984, the year after he died, Balanchine feels elegiac, arguing for Balanchine’s significance in the world of dance just as he had left it. The directors make excellent use of old news footage and rehearsal tapes as well as performance video, including excerpts from a press conference on the creation of Lincoln Center and dance numbers from the early sound film Dark Red Roses (1929), with choreography and performance by Balanchine. In one especially poignant sequence, we see footage of him in rehearsal, coaching Mikhail Baryshnikov in the title role of Prodigal Son, juxtaposed with a later performance of the ballet.