There are two narrators fighting for control of A Tale of Love and Darkness (Harcourt, $26), though only one author’s name appears on the spine. In essence, it’s the story of how one defeated the other, how he cast off the old parental ties to prewar Europe and reinvented himself in the desert on a kibbutz. But the victory is never complete, and the vanquished keeps reasserting himself in the story. Meanwhile, Arabs are shelling Jerusalem, the British are standing idle at their posts, and Zionism is not yet a loaded political epithet. To put it mildly, the two authors were born in interesting times.

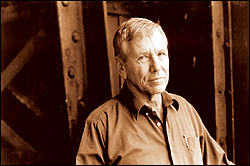

The writer of record, of course, is the prolific Amos Oz, and his rival is Amos Klausner—the surname belonging to his father’s family from Odessa and Polish-controlled Lithuania. Yehuda Arieh Klausner emigrated to Palestine in the late ’30s along with most of his family. There, he met and married Fania Mussman, from another Jewish immigrant family. Their son, born in 1939, is Amos, and he wants nothing to do with the musty old European intellectual traditions revered by his parents, although that realization takes a while in coming.

Oz became Oz at 15, by a process as serpentine as his memoir. He’s intentionally indirect about the chronology and nomenclature of the Klausners and their assimilation. It would be easy for him—and very helpful for the reader—to provide a family tree or timeline in an index, but that would be a Klausner thing to do: “secular, enlightened, rationalistic, idealistic, militantly optimistic and progressive.” Young Amos’ father is a scholar trapped in a low-status librarian’s job; he believes that hard work and merit will somehow lift him to a real academic’s position closer to that of his distinguished Uncle Joseph. (The latter and various other literary and political luminaries revolve around the Klausner household.) But, as Amos and his parents discover, those qualities that garnered respect in the old world lost their currency once the shooting started—and the shooting isn’t over in pre-1948 Palestine.

BUT WHILE THE Klausners’ generation had a faith in Zionism as a rational force for good, Oz writes, “when the Arabs look at us, they see not a bunch of half-hysterical survivors but a new offshoot of Europe, with its colonialism, technical sophistication, and exploitation, that has cleverly returned to the Middle East—in Zionist guise this time—to exploit, evict, and oppress all over again.”

Oz is a creation of that new political reality: families packed into his apartment during Arab shelling, friends killed in the street, food shortages, and so on. He’s a new, self-named Israeli—Oz, or “strength” in Hebrew. He’s also the antithesis to young Amos Klausner—a pale, spoiled, bookish only child, nothing like the robust young kibbutzniks fighting with the Irgun and Stern Gang, those who labor in the fields with their sun-browned skin and strong muscles.

But Amos Klausner is strong, too, in his memory and power of observation during childhood. With startling clarity, the author describes being lost in a ladies department store, visiting an eminent Arab family with his cousins, and simply lying on his back and staring at the darkening, dusky sky as a 6-year-old, sucking a stone in his mouth: “And all the thoughts that stone conjured up you are never to forget, a universe inside a universe inside a universe.”

Like most literary memoirs, Love and Darkness is the story of how the author became a writer, how Klausner was transformed into Oz. But it’s also a journey in reverse, a reclaiming of his past and family history. Most important in this project are his parents, who couldn’t make the leap from 19th-century progressivism to harsh 20th-century reality, then placed “the full weight of their disappointments on my little shoulders.” They did their best with their son, and the book records their daily life, however shabby and humble, in loving detail.

His mother, however, could not bear the strain of assimilation. She killed herself, we learn early in the memoir, when the author was about 12. Oz depicts her final discontents— her fatigue, her walking alone through rainy Tel Aviv without an umbrella—with the compassion and imagination of a novelist. A few years after her death, the son will leave his dad for the kibbutz, where he would change his name and remain for almost 30 years. “After my father died,” he writes of his prior silence about his mother, “I hardly ever spoke about him either. As if I were a foundling.”

That’s an impression Love and Darkness overpoweringly corrects. Oz is no orphan, and his great achievement is to make the Klausner family live on today.

NextBook presents Amos Oz at Benaroya Hall (200 University St., 888-621-2230), 7:30 p.m. Mon., Dec. 6.