History is written by the winners, and so the instant history that’s written about this year’s presidential election is that it was decided by people concerned with “moral values.”

All sorts of yammering has followed about the need for Democrats and progressives to be more respectful of the cultural and social conservatism of our country. But let’s back up a moment.

What, exactly, are “moral values”? What does the phrase mean? When the same exit polls that told us Kerry would win asked voters what they cared about, what did voters who cited morals think they were describing?

There are a lot of different moral values out there other than the ones prescribed by evangelical Christians. And maybe, just maybe, it’s time for progressives to start talking about our moral values.

Frame it with religion if you want. There’s a lot more in the Bible, for example, that encourages liberalism than conservatism: caring for our neighbors. Turning the other cheek. Thou shalt not kill. The meek shall inherit the Earth. The generally dim view of usury and greed. Being stewards, and treating the Earth with respect.

In politics, what we are really talking about is not just the personal behavior (or level of public devoutness) of our politicians. That’s significant, of course; just ask Bill Clinton. But we also need to examine the moral implications of policy decisions.

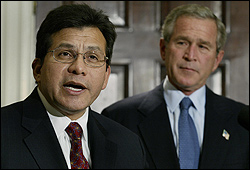

Let’s go there. President Bush’s nominee for attorney general, White House Counsel Alberto Gonzales, is somehow considered less polarizing than the man he would replace, John Ashcroft. Yet Gonzales is the guy who wrote the memo justifying use of torture against prisoners in the war on terror, calling the relevant provisions in the Geneva Conventions barring such practices “quaint.”

Providing a legal justification for torture is something that offends my moral values.

You want morals? What’s the moral justification for a war that, in the name of their so-called liberation, has claimed the lives of 100,000 (and counting) Iraqi civilians? What’s the moral justification for economic policies that allow the wealthy to skate on paying their fair share of the bill for the common good, while racking up a debt that our grandchildren will be paying for decades to come? What’s so moral about a fabulously wealthy country in which children go hungry and health care access is a dubious proposition for the nearly 50 million uninsured? Where are the morals in policies designed to make the rich richer and the poor poorer?

The problem with the current interpretation of moral values is that it is being juxtaposed against the concerns of people who care about specific issues and policies, as though the issues themselves don’t have any moral value. But they do. Politicians can trumpet their faith all they want, but the policies they implement are the real manifestation of their moral universe. When we ask what politicians are doing to make the world a better place, part of that question is a very specific notion of how the world could be made better.

It’s time that progressives laid out our moral vision: a country that values its freedoms but also values the sanctity of every life—not just at the fetus stage. We need to embrace the notion that every life has dignity and value and deserves respect and a fair opportunity. That’s the justification for a wide range of social services now being gutted by conservatives. Helping the less fortunate is not just a policy that makes sense for a better-functioning society; it’s also a moral imperative. For too long, progressives have been squeamish about citing those moral imperatives, as though compassion were the third rail in American politics.

The phrase “moral values” in its current political guise might be nothing more than a polite way of categorizing people opposed to gay marriage. But its use is an opportunity, for progressives and liberals, to make the case that ours is a sensibility deeply grounded in a moral vision shared by a majority of Americans. Using the platform of moral values in coming years will allow progressives to be something more than a loyal, if relatively powerless, opposition.

We can become America’s conscience.