Albert Ayler was—wince if you say it— a minor musician. Not bad, not unoriginal, not incapable of interesting or worthwhile work, not by a long shot. Advanced: definitely. Influential: indisputably. A musician’s musician: absolutely—in the short course of his career as a mostly tenor saxophonist, from 1962 to 1970, he played with everyone who was anyone, and a lot of people who weren’t. The stories of the early years abound in the book that accompanies the new 10-CD set Holy Ghost (Revenant): a polite, well-dressed man who showed up with a saxophone in a little briefcase, asked if he could sit in, and on getting the nod, immediately launched into a free-form barrage that continued until the other musicians, the audience, or both fled with their hands over their ears. What’s not to love?

Theoretically, Ayler’s work is fascinating. His pieces (the catalog is relatively tiny) were mostly very brief themes, with echoes of much older New Orleans brass band music, that served as springboards for squealing, outer-limits free improvisation. (He did write one terrific, slightly longer tune, “Ghosts,” a bold march that the late saxophonist Gary Windo thought “ought to be played in football stadiums when touchdowns are scored.”) But there’s something off-putting about most of his recordings, largely thanks to his invariably defining “freedom” as edge-of-bearability provocation. That may have something to do with Ayler’s religious visions, about which he wrote and spoke extensively later in his life. If you announce that you’re creating art in accordance with a spiritual truth that’s been revealed to you, nobody can say, “No, you’re not”—besides which, you’re also suggesting that it’s somehow unfair to judge your work by any other standard, bait that all too many people pick up on.

Ayler did the single most significant thing a cult artist can do for his subsequent reputation: dying young, at 34, and under mysterious circumstances. His recorded legacy, though, is mostly transitional or provisional—short-lived groups caught on the fly, chance encounters with a rolling tape, and one legendary misfire, 1968’s New Grass, an attempt to cross over to rock audiences that fails so spectacularly, it’s become a bit of a cult object. And Holy Ghost dives even deeper; it’s all unreleased recordings. (Or almost unreleased. The liner notes describe one earlier edition of some of this material as “nefarious.”)

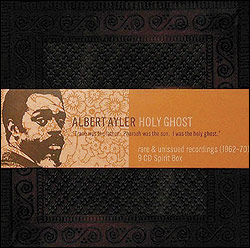

Holy Ghost is a gorgeous object—a plastic “spirit box” (molded on a wooden original), containing seven full CDs of music, two more of interviews, another with two early tracks Ayler recorded in the Army, a beautifully designed 200-page hardcover book, reproductions of Ayler-related ephemera (a note scribbled in a hotel, a late-’60s jazz ‘zine with articles by and about him, a photograph of the saxophonist as a boy, and more), and a dogwood blossom in a glassine envelope. You’d think that it would have to contain some spectacular recordings to be worthy of this kind of treatment, but the point isn’t its musical contents alone. What the box presents is the full-on Ayler experience: the artist as a misunderstood prophet and as a vector of ideas that changed his culture. It’s essentially a biography built around newly unearthed primary documents, most of which are recordings.

The actual music of Holy Ghost includes one sequence that’s on-and-off terrific on its own merits (a full-force 23-minute set from the Newport Jazz Festival in mid-1967), one collector’s grail (the Ayler quartet’s performance from John Coltrane’s funeral a few weeks later), one historical landmark that’s pretty tough listening (“Four,” the first recorded long-form pure improvisation, with Cecil Taylor in late 1962), and a whole lot of oddities—which are mostly the leftovers of leftovers, given how extensively Ayler’s short recording career has already been documented. There are muddily recorded club shows (two discs’ worth from the April 1966 shows that introduced violinist Michel Samson to the band), three 1962 tracks with a Finnish jazz group that seems to barely realize what it’s in for, a Pharoah Sanders live recording on which Ayler gives Sanders’ material the sort of mauling Sanders had given Coltrane’s “Naima” on the latter’s Live at the Village Vanguard Again!, a couple of 1969 pieces by the Don Ayler Sextet (featuring Albert but led by his brother, who’s basically Andrew Ridgeley to his George Michael), and, scraping the barrel so hard splinters come off, outtakes and rehearsals from New Grass.

Does Ayler deserve this ultradeluxe shrine? Sure; who doesn’t? This kind of deep, careful attention to a 10-year span in any active musician’s life would be intrinsically interesting, and the compilers’ incredible dedication to getting the details about Ayler’s life right—and lovingly presenting them in the context of ’60s underground jazz culture—makes the whole package absorbing to hear and read. Ben Young’s analyses of the performances on the CDs are thoughtful and insightful. But the recordings here aren’t likely to convert anyone who hasn’t got the Ayler bug already. “Trane was the father. Pharoah was the son. I was the holy ghost,” the outside of the box quotes him as saying, and Ayler’s self-mythologizing is exactly the problem: Putting him in the same rank as Coltrane and Sanders is giving him way too much credit. To be their kind of great musician, it’s necessary to be revolutionary, which Ayler was; but it’s not sufficient.