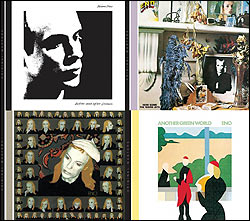

BRIAN ENO

Here Come the Warm Jets

Taking Tiger Mountain

(By Strategy)

Another Green World

Before and After Science

(all Astralwerks)

Brian Eno has done such a good job of disappearing up his own obliquely strategic ass over the last 30 years that you’d be hard-pressed to remember that he was once a writer of (excellent) songs. We’re far more comfortable with him as a theorist and a pundit and sound gardener—yet here are the four albums he sang on, pesky reminders of his path not taken. None of them was really ever unavailable, and the old CDs still sound fine to me. These subtle remasters are a bit like transferring an etching from a piece of rice paper to Lucite. And the music is recommended to anyone who enjoys the Beatles, Gilberto Gil, Pavement, the Beta Band, or Timbaland: self-aware but never self-conscious pop songs with twists and invisible improvisations and funny noises. Here Come the Warm Jets (1974) is the first, the glammiest, the rockingest, and the funniest. It opens with “Needles in the Camel’s Eye,” which takes place in an alternate universe where Sterling Morrison played with the Crickets instead of the Velvet Underground, and ends with the title track’s flatulent soundtrack triumphalism. The playing is impeccable, drawing on the cream of English prog-rock, from vocalist Robert Wyatt to King Crimson guitarist Robert Fripp to, um, Genesis drummer Phil Collins. Eno’s own inability to play anything other than the studio (he gave musicians instructions such as “play like a Tesla coil”) kept things unpredictable. Fripp’s solo on “Baby’s on Fire” is a series of Windsors and half-Windsors that never quite knot. Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy) (1974) is Eno’s incontestable masterpiece. Some bands have spent their whole careers trying to remake “Third Uncle,” pre-emptory new wave so taut it might be the thrumming of the human nervous system itself. Eno was also mastering his instrument. What’s the lead voice on “Burning Airlines Give You So Much More”? A zither played with tongs? A glass xylophone? Eno melted into the studio entirely for 1975’s Another

Green World. This is the start of the program music, the ambient music, and all future product marked “Eno.” It contains a few songs, a few flashy moments (Fripp’s solo on “St. Elmo’s Fire,” not coincidentally the best of the songs), but mostly the album is moody synth vapor against a dark-woods backdrop. Soon after would come the ambient years (moody synth vapor as an end in itself), and his classic Bowie trilogy of Low, Heroes, and Lodger (moody synth vapor under someone else’s songs). On his way there, he released 1977’s Before and After Science, and no wonder it feels like an afterthought, though it contains “King’s Lead Hat,” his nerviest rocker, and “By This River,” a dream combo of sleepy Stereolab and Arvo Part. Science is a failed masterpiece—for every “No One Receiving,” matte silver funk, there’s a “Here He Comes,” a dull ballad. But setting the tone for the next 30-odd years of semipopular rock is a tough act to follow. JESS HARVELL

the GRIS GRIS

The Gris Gris

(Birdman)

“Gris-gris” is a New Orleans slang term for voodoo amulets or incantations that’s also used as a reference to drug taking; it’s also the title of Dr. John’s 1968 debut, which is where this Oakland-via-Texas band’s frontman, Greg Ashley, got it. Already, you have a handful of clues as to what the Gris Gris are onto—namely, they make spacey garage-rock exotica. (Think Spacemen 3 fused with Os Mutantes plus a case full of castanets.) The leadoff track, “Raygun,” barely whispers as it emerges; the opening bass notes are just pitter-pats before the kick drum comes in with what can hardly be described as a kick. Once in full swing, Ashley’s lament seems to come from around some distant bend, while the guitars belong to gypsies. Halfway through the eight-minute track, the distant, exotic melancholy has turned itself inside out and become a wall of feedback and noise, but Ashley returns at the very end, softly singing, “Raygun, raygun/Da da da da dum,” as the song disappears. Elsewhere the Gris Gris offer straightforward Stonesian garage (“Necessary Separation”), Latin-leaning psych/pop (“Medication #3”), and the kind of humble garage-born longings that seem to have gone missing from the rough-and-tumble revival’s songbooks (“Me Queda Um Bejou”). If you’re inclined to need someone, you’ll be glad the Gris Gris brought them back. LAURA CASSIDY

The Gris Gris play Sunset Tavern with the Cops and Invisible Eyes at 9 p.m. Fri., Aug. 27. $7.

VARIOUS ARTISTS

Mento Madness: Motta’s Jamaican Mento 1951–1956 (V2)

Stanley Motta invented the Jamaican recording industry. He began issuing discs of a locally brewed form of calypso—mento—in the early ’50s, prefiguring ska and reggae-biz masterminds such as Clement “Coxsone” Dodd and Leslie Kong. Mento Madness collects 18 benchmarks of the style, including the country’s first homemade 78 (Lord Fly’s “Medley of Jamaican Mento”) and its first to be released elsewhere (Harold Richardson and the Ticklers’ “Glamour Gal,” which appeared in the U.K. on Melodisc in 1952). Madness is no mere history lesson, though. The Jamaicans’ take on calypso is every bit as diverse (R&B-ish sax here, a banjo solo there) and funny as Trinidad’s. Philosophical, too—”Monkey Talk” by Hubert Porter with George Moxey & His Calypso Quintet finds said signifying animal holding evolutionary theory up to the light, concluding that Darwin got it backward: “A monkey wouldn’t go home at night dead drunk/And try to pull his sleeping wife from her bunk/Neither would a monk wake his neighbors up/By smashing plates, dishes, saucers, and cups.” “Glamour Gal” similarly plays the dozens, echoing Louis Jordan’s “Beware” while adding complaints about bleaching cream and tricky brassieres. Monty Reynolds & the Shaw Park Calypso Band’s “Me Dog Can’t Bark” wryly protests antinoise laws, hinting that the government might also like to shut up poor people. Motta got out of the record game after 1956, yielding to the burgeoning tide of rockin’ American sounds that fed ska. But roots fans will want to hear these excavations from his vaults. RICKEY WRIGHT

NEUROSIS

The Eye of Every Storm

(Neurot)

Neurosis, post-hardcore gone psych-metal tough guys from the Bay Area, are the sonic equivalent of Robinson Jeffers’ brawny, atavistic nature poetry. For the uninitiated, singer Steve Von Till’s anguished he-man vocals can seem a bit over the top, but they have to be in order to sell the outsized beats and mythic lyrics—kind of like Juvenile. They want to be a force of nature, not just a rock and roll band. Not since the heyday of Swans has a band done dirge and drone so well with nary a blink or a wink. The band’s multidimensional heavy music has a deep dub weightiness that gives the reverberations of bass and drums a stark, breathless desert landscape feel. Some people might substitute the word “oppressive” for “breathless,” but then, music as a “force of nature” can often feel like being hit over the head with a club, dragged out to the desert, and left to die whilst pondering the pretty cactus flowers. The Eye of Every Storm hypnotizes like their last, 2001’s A Sun That Never Sets, but the new one adds a little more of the psychedelic electronic work that their alter ego Tribes of Neurot lay down for the acid-damaged set. Steve Albini makes sure the metallic maelstroms shine and glisten in the mud. But just as important as the soul-satisfying guitar noises on Storm are the moments of melancholia, silence, and light that peek through the dark clouds. SCOTT SEWARD

LANSING-DREIDEN

The Incomplete Triangle

(Kemado)

“Charm is in limited supply/And it’s refusing to stretch/That indefinable nothing somehow motivates you.” That couplet, from Joe Crow’s 1983 single “Compulsion,” aptly describes the uneasy relationship between art and commerce. Each is predicated on the search for an elusive quality that will set it apart from the other while maintaining the ties that sustain them both. The debut album from Brooklyn-via-Miami artists’ collective Lansing-Dreiden walks this fine line with aplomb. Despite being lumped in with the Williamsburg electroclash bunch (Fischerspooner, W.I.T.), the publicity-shy group has been exploring similar themes in various media since its inception in 1999. Known mainly for the infrequently published journal Death Notices, Lansing-Dreiden made their first foray into sound with the 2003 release of The Incomplete Triangle; like their previous work, it uses the polished aesthetic of synthy ’80s alt-rock as a jumping-off point. Luckily, Kemado’s rerelease has filed away none of the rough edges that make the album so compelling. Filtered through a prism of dated effects, the aloofness that serves as a foundation for the songs, represented here by layers of echo that nearly obscure the lyrics, loses its power. Lyrics like “I’ll never let you go” (“I.C.U.”) are stripped of their chill (and redeemed of their inadvertent silliness) by a sudden, unexpected hitch in the singer’s voice. Any effect created by the washes of synthesizer in “Glass Corridor” is punctured by an endearingly off-key “yeah” that appears just outside of the beat throughout the song. Moments like this pop up throughout The Incomplete Triangle. Hints of chaos seep through the slick production, and the aftereffect is haunting, a fever dream barely remembered but chilling nonetheless—the “indefinable nothing” found at last. DONNA BROWN

OMARA PORTUONDO

Flor de Amor

(World Circuit/Nonesuch)

Those of us too young to remember the artistic exchange between Cuba and America that preceded the Kennedy administration may have called World Circuit head Nick Gold’s motives into question during the minor backlash that accompanied the Buena Vista Social Club. There were fears that he might overstep the bounds of cultural anthropology and give his newfound discoveries a scrubbing akin to the dramatic bleaching effect that a heightened amount of carbon dioxide has created on the coral supply in the world’s oceans. But to Gold’s credit, he has held ensuing projects to a ruthless standard of quality (no slumming duets with Bonnie Raitt—I’m looking at you, Césaria Évora) as the group has spun into its own cottage industry. Omara Portuondo doesn’t figure as prominently in Wim Wenders’ 1998 BVSC documentary as do magnetic personalities like Ibrahim Ferrer and pianist Rubén González. Still, Portuondo is the Titania to Ferrer’s Puck and González’s Oberon in Wenders’ recast A Midsummer Night’s Dream. On Flor de Amor, she carries herself with a prim, regal authority that belies her proletarian charms. And, oh man, can she belt: Ry Cooder described her as “the Cuban Edith Piaf” upon his first visit to Havana, which barely scratches the surface of her husky, resonant voice. Portuondo has run herself ragged on previous solo work, attempting to interpret as many styles as possible, but here she wisely limits herself to a more fitting midtempo bolero, and on “Amorosa Guajira,” she dominates the spare arrangement, proof that this social club—unlike the Havana nightspots where she rose to prominence in the 1940s and ’50s—is no sausage fest. NICK GREEN

BRANDY

Afrodisiac

(Atlantic)

The idea of the R&B diva’s coming-of-age album is so familiar—Mary J. Blige’s Mary, Janet Jackson’s janet, lots of other records whose titles are the woman’s first name—that when Brandy graces the cover of Afrodisiac in the guise of the hottest mom likely to appear on 106 & Park this summer, it hardly registers as a gutsy move. In the past three years, the singer “married” musician Robert Smith (not the Cure frontman, sadly), had a child, split up, and let an MTV crew film much of it. So, of course, she’s got a song to sing about it, and one more “mature” than “Sittin’ Up in My Room” or even “What About Us?,” the dark electroclash hit from 2002’s Full Moon. But if Brandy’s willingness to get personal on her fourth CD isn’t a reason to wake Lauryn Hill, the style with which she brings it off is. Hiring Timbaland to produce the bulk of the tracks didn’t hurt: The title cut is built on a bed of breathy aahs that conjure an around-the-way Enya; the stutter-stepped “Who Is She 2 U” funks up Alicia’s 88 keys; a hypnotic Iron Maiden sample drives the “Cry Me a River” sequel “I Tried.” And Brandy’s confidence is bracing; check the combination of regret and sass with which she refers to “the weight on my fourth finger, left hand,” or the presence of mind she exhibits while surrounded by Kanye West’s swirling strings in “Talk About Our Love.” She sounds like she’s done waiting to exhale. MIKAEL WOOD

BEENIE MAN

Back to Basics

(Virgin)

Beenie Man makes the girls dem sugar, but sometimes he just makes me wanna holler. At his best, when delivering gully nastiness (1997’s “Who Am I?”) or apocalypso hymns to Jah (“Moses Cry”), he’s unstoppable, maybe the best modern ragga DJ. And what is he best known for in America? Toothache- inducing R&B nonsense. There’s little evidence of this on Back 2 Basics, and he should kiss Sean Paul’s ass for breaking the iron law that dancehall crossover stars need to make albums packed with hip-hop gray water and lite pop. This is straight ragga, albeit made with an entertainer’s eye. “Good Woe,” his version of Jamaica’s inescapable “Coolie Dance” riddim (the only reason to listen to rap radio this summer), bites the Patty Smyth/Don Henley duet “Sometimes Love Just Ain’t Enough” for the chorus. “If a Neva God” is gospel rewritten for a Carnival cruise ship, and the surprisingly affecting “Back Against the Wall” utilizes an acoustic guitar and nothing else. But the burial tune of the whole record actually belongs to Timbaland, who’s spent so long trying to rewrite the “Diwali” rhythm (see Sean Paul’s “Get Busy”) that he’s finally outdone those pesky Jamaicans. His “All Girls Party” uses a rollicking harpsichord, some Vocodered doo-wop harmonies, a Japanese ingenue, and a martial snare crack fed into a primitive sampler and belched out in nasty chunks. Of course, instead of this monster tune, Beenie will probably release another me-love-all-de-ladies songs for the next single. But hey—you can’t teach people good taste. JESS HARVELL